Helen Wills – one of the greatest female tennis players of all time.

Charlie Chaplin once wrote that the most beautiful sight he had ever seen, and presumably he had seen a few, was ‘the movement of Helen Wills playing tennis’. Wills, a pretty 23 year old American, played the game with an unhurried and seemingly effortless style and she was in her heyday when Vogue magazine in their June 1929 issue wrote:

One very noticeable thing about our girl champions at Wimbledon is their grace, distinctly the reverse of what some people have prophesied – that hard exercise and strain would thicken the ankles, coursen the complexion, and lead to general ungainliness.

Helen Wills was certainly never accused of ungainliness but her composed and rather dispassionate on-court behaviour lent her the not particularly affectionate nickname of ‘Little Miss Poker Face’. The designer and tennis player Teddy Tinling described her as the Garbo of tennis not only because of her undoubted beauty but that she “always wanted to be alone and away from her fellow competitors…”

The be-stockinged rivals Helen Jacobs and Helen Wills in 1929.

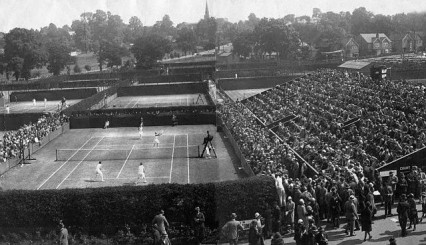

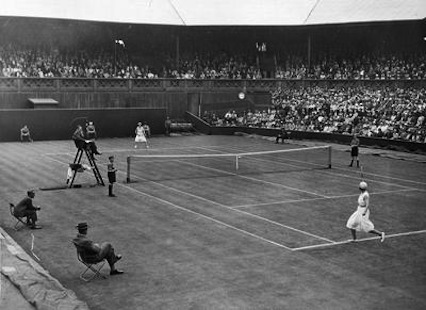

Wimbledon Championships, 1929

In 1929 Helen Wills, at the age of just 23, was appearing at the famous South London tennis tournament for the sixth time and was already five times Wimbledon singles champion. That year she wore a white sailor suit with a pleated knee-length skirt, white shoes and the white visor for which she was famous. The Wimbledon crowd were more than used to seeing her on the centre court but that year they took a particular interest in what she was wearing. Especially on her legs.

Earlier that summer there had been an enthusiastic debate in much of the press about the wearing, or more specifically the non-wearing, of stockings by female tennis players. The Lawn Tennis Association along with the All-England Club, organisations then as now not exactly known to be at the vanguard of modern fashion trends quickly let it be known that they were considering prohibiting, what was known at the time as, ‘bare-leg tennis’.

The Daily Mail reported that some players were ‘indignant’ with the possible ban, notably the two American tennis stars – the Helens Wills and Jacobs. They were reported as surprised with the proposed veto as ‘bare-leg tennis’ was already popular in America and in France.

Helen wills and Helen Jacobs suitably wearing stockings at Wimbledon in 1929

In the end the committee of the All-England Club sensibly decided against a formal ban but made it be known that they would rely on the good taste and good sense of the players involved. Indeed Miss Wills stated in the London Evening News:

I definitely have decided to wear stockings in the Wimbledon tournament. As soon as I heard that the Wimbledon authorities might object to bare legs I reached a definite decision and I shall not alter it.

Wills easily beat Jacobs 6-1, 6-2 and in fact the only singles match Helen Wills ever lost at Wimbledon was her first final when she lost against the British player Kitty Godfree in 1924 when she was only eighteen.

The stockings, or lack thereof, controversy was brought about by changes in the manufacturing of stockings during the previous thirty years or so. At the turn of the century 19 out of 20 pairs of stockings were black but with the relatively short skirts of the 1920s more and more stockings were made with finer knits and in a range of paler colours.

The stockings were held in place with a combination of suspenders and garters although the Frenchwoman Suzanne Lenglen, the first proper international female tennis celebrity, wore white silk stockings with the tops rolled over her garters in what was called the ‘American’ style. She was also the first major tennis player to play without a corset early in her career for which she was often known by many British tennis fans as ‘the French Hussy’.

American garters from 1930

Lord Aberdare in his Story of Tennis described when Lenglen first appeared at Wimbledon in 1919:

Suzanne acquired strength and pace of shot by playing with men, and for playing a man’s type of game she needed freedom of movement. Off came the suspender belt, and she supported her stockings by means of garters above the knee; off came the petticoat and she wore only a short pleated skirt; off came the long sleeves and she wore a neat short sleeved vest.

Her first appearance at Wimbledon caused much comment, but the success of her outfit led to its adoption by others. In her first championship, she wore a white hat but on subsequent occasions she wore a brightly coloured bandeau which was outstandingly popular until challenged by Miss Helen Will’s eyeshade in 1924.

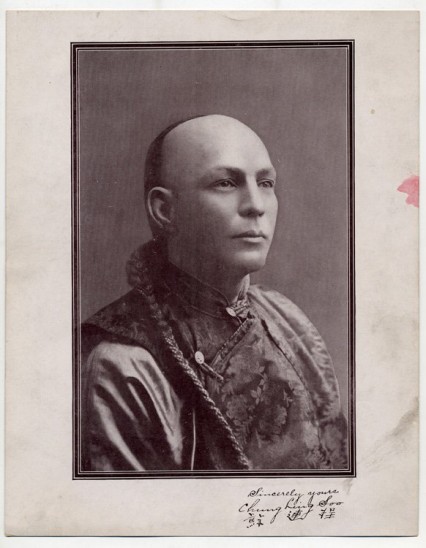

The corsetless ‘French Hussy’ Suzanne Lenglen in 1924.

A portrait of Suzanne Lenglen from 1924. She often drank brandy while changing ends.

In fact Lenglen’s look: her bandeau (known to some as a ‘headache band’), rolled stockings, knee-length pleated skirts became the symbol of the flapper in the 1920s. It may have been the first time a sports figure influenced general fashion around the world.

Incidentally, Helen Wills and Suzanne Lenglen only played one match together, at a small tournament in Cannes in 1926. It was billed as Match of the Century and it was estimated that three thousand spectators crammed into the stands at the Carlton Club. Lenglen won in straight sets 6-3 8-6 but it seemed that she realised her reign was close to coming to an end and she turned professional soon after. They were never to play together again.

Helen Wills v Suzanne Lenglen in Cannes 1926

All of the women players wore stockings at the 1929 Wimbledon championships. Although, as far as tennis-playing women were concerned, it was now the beginning of the end for the restrictive garments.

Much against the newspaper’s will, the Daily Mail’s prurient eyes were turned away from the legs of female tennis players and later that summer they started to look at what men were wearing instead. After reporting that men were ‘shy creatures’ and would ‘rather die than wear anything unconventional in public’, on 31 August 1929 the Daily Mail wrote:

Now that the the highest lawn-tennis authority has decided that it has no power to forbid women to play that game bare-legged, it was inevitable that attention should be concentrated on the oddities of male dress. It seems to be universally agreed that male dress at the present time is the most unhygienic, inartistic, somber, and depressing form of costume that the mind could well imagine. But the difficulty is to get the idea of a brighter, more hygienic, and more picturesque attire into the mind of the mere male.

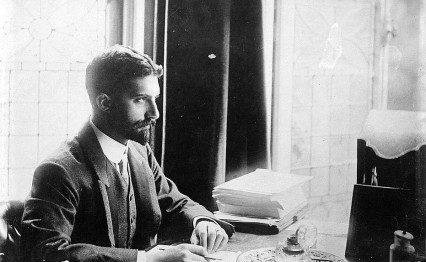

Recently the press had featured a photograph of a Dr Alfred Charles Jordan a renowned radiologist cycling to his office in Bloomsbury. What fascinated and what slightly horrified readers was that he wore shorts with his jacket. This was utterly unknown at the time for anybody working in a city – shorts were for scouts and maybe a hiking holiday; they weren’t even worn by men playing tennis at the time.

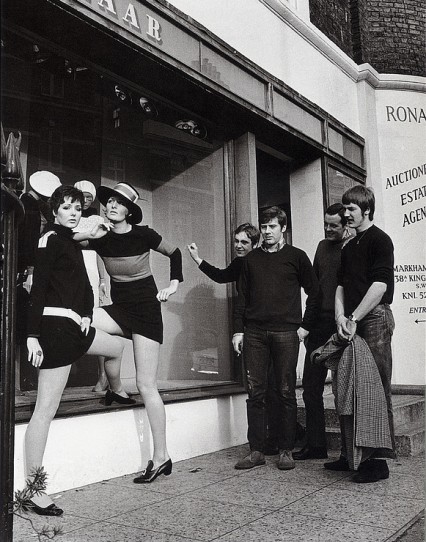

Members of the Men’s Dress Reform Party including Dr Jordan on the far right. July 4th 1929.

Jordan was the honorary secretary of the Men’s Dress Reform Party which had announced its existence on 12 June 1929 just twelve days before the be-stockinged Helen Wills had walked out for her first round match on the centre court at Wimbledon. The organisation’s first aim was to improve men’s health by changing what they wore and in early MDRP literature it complained that:

Men’s dress has sunk into a rut of ugliness and unhealthiness from which – by common consent – it should be rescued…Men’s dress is ugly, uncomfortable, dirty (because unwashable), unhealthy (because heavy, tight and unventilated)…it is desirable to guard against the danger of mere change for change’s sake, such as has often occurred in women’s fashion. All change should aim at improvement in appearance, hygiene, comfort and convenience.

An article in the tailoring magazine Tailor and Cutter probably reflected what the majority of men were thinking when confronted by the rather strange clothes worn by members of the MDRP. The anonymous author of the piece wrote that modern male dress depended on:

A loosening of the bonds will gradually impel mankind to sag and droop bodily and spiritually. If laces are unfastened, ties loosened and buttons banished, the whole structure of modern dress will come undone; it is not so wild as it sounds to say that society will also fall to pieces…Such restraints were not noxious: they were the foundation upon which civilisation rested and protected men from savagery and decadence.

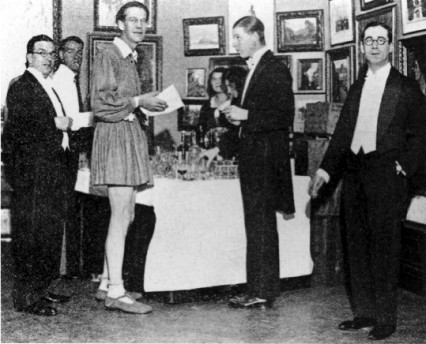

Two men modelling ideas entered for a Dress Reform competition.

Members of the Men’s Dress Reform Party in Great Russell Street.

The MDRP was an off-shoot, and shared premises with, the New Health Society formed in 1925 and situated at 39 Bedford Square in Bloomsbury. Dr Jordan was a founding member but the chairman of the organisation was another doctor, Caleb William Saleeby, who had originally chaired the Clothing sub-committee of the New Health Society but had also founded the Sunlight League in 1924. It was formed in London to educate the public about ‘Nature’s universal disinfectant, stimulant and tonic’ and advocated heliotherapy – direct exposure to the sun.

The League campaigned for a variety of causes including mixed sunbathing and the relaxation of the rules for appropriate attire for sunbathing. Towards the end of the 1920s new-fangled sunbathing clubs were opening around London including Finchley and Sidcup while the Yew Tree Club devoted to physical culture and nudity opened in Croydon.

Compared with on the continent, especially in Germany, nudism remained a minority activity in England and it rarely strayed from its suburban, home-counties roots. The clubs had strict conventions and rules of etiquette designed to convince a doubting public that sex was the last thing on the nudists minds. And looking at some pictures maybe it was.

Dr Caleb Saleeby

Rather shy nudists sunbathing at the Yew Tree Camp in Croydon

The first nudist conference held in England by the Sunlight League

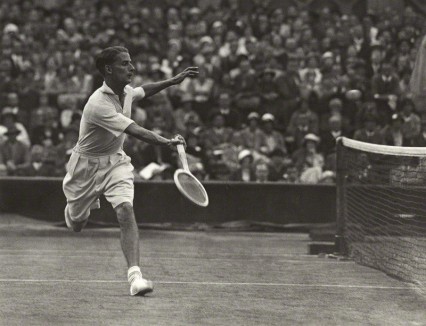

Dr Saleeby, as chairman of the MDRP, wrote a letter to the Lawn Tennis Association in 1929 encouraging it ‘to persuade men to give up the handicap of heavy trousers and play in shorts’. The first man to have famously worn shorts at Wimbledon was Henry ‘Bunny’ Austin (his nickname comes from a character in the comic strip Pip, Squeak and Wilfred). Except he wasn’t. In reality the first man to experience fresh air against his legs while playing tennis at Wimbledon was actually the relatively unknown English player Brame Hillyard who wore them on Court 10 a year after Dr Saleeby’s letter in 1930. Despite the freedom his shorts must have given him he promptly lost, and he was hardly ever heard of again.

Two years later in 1932 Bunny Austin, born in 1908 in South Norwood, eight miles or so away from Wimbledon, but educated at Repton and Cambridge, became the first person to wear shorts on Centre Court and thus in front of the world’s press. He claimed that the traditional white flannels were heavy and restricting; John Kieran wrote about him in the New York Times that year:

“With his white linen hat and his flannel shorts, the little English player looked like an AA Milne production.”

Bunny Austin wearing shorts at Wimbledon in 1933

Bunny Austin, despite wearing shorts, lost in the final to the American Don Budge and the Englishman’s reward was a £10 gift voucher redeemable at a high-street jewellers (the winner of the Men’s and Women’s final will earn £1,150,000 this year). Austin was the last Briton to appear in a Wimbledon Singles Final when he was runner-up in 1938. During the war he became active in the Christian pacifist movement and was criticised in the press as a conscientious objector. It wouldn’t be until 1984 that Austin was again allowed to be a member of the All-England Club.

The MDRP, although pretty well forgotten these days, had some success in getting its message across during the first years of its existence. It held annual parties, in order to “give every man a chance to show how he can look and feel his best by the costume he will evolve for this unique occasion.” It was also possible to find MDRP approved clothing in some shops in London including the famous Austin Reed on Regent Street. It also had an official shop and a relatively successful mail-order service.

Some members of the Men’s Dress Reform Party were more radical than others.

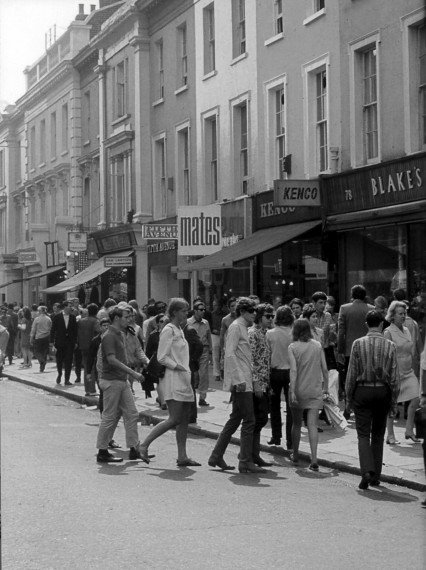

Realistically the MDRP did little to turn general male fashion around except maybe in holiday and athletic wear. A major shift in men’s clothing didn’t happen until after the war when new fabrics and the rise of American style, with its preoccupation with leisure-wear, radically changed men’s appearances in the 1960s.

In 1931, two women players flouted the unofficial clothing rules at Wimbledon. Joan Lycett, who was actually born Joan Austin and was the sister of Bunny, played without stockings, but by now the newspapers and the watching crowds, used to seeing stockingless players away from Wimbledon, seemed to hardly notice. Lycett’s opponent, however, did cause a sensation. Lili de Alvarez ‘the gay senorita’ from Spain played at Wimbledon wearing a ‘white trousered frock’. The Times on 24 June 1931 wondered, ‘which were the more wonderful things – divided skirts or bare legs?’ On the same day the Daily Sketch saw de Alvarez’s ‘trousered tennis frock’ as yet more evidence that women had a ‘masculine fixation’:

The claim of women to equality with men is understandable, but that so many of them should wish to imitate the appearance of the less beauteous sex is not so easy to understand. It began with bobbing, and reached its logical hirsute conclusion in the Eton crop. And, having lost her hair, many a girl is now making strenuous attempts to lose her curves. And concurrently with these changes the conquest of trousers had been steadily proceeding…although mere man may regret the lose of feminine furbelows more than he resents the theft of his trousers, he realises that it is useless to rail against the spirit of the age. Whether we like it or not, girls will be boys.

Joan Lycett and Lili de Alvarez wearing her ‘trousered tennis frock’ on Centre Court in 1931

Joan Lycett.

Lili de Alvarez playing at Wimbledon in 1926

Helen Wills and her Husband FS Moody

Helen Wills, who became known as Helen Wills-Moody after marrying the business man Frederick Moody in December 1929 (she had met him at the match with Suzanne Lenglen), went on to win 31 Grand Slam tournament titles during her career including eight single titles at Wimbledon. Incredibly she reached the final of every single Grand Slam singles event she entered but, as was common in those days, never played at the Australian Championships.

The rivalry between the two Californian Helens reached a head when they played against each other in the final of the 1933 US Championship at Forest Hills. Wills had always beaten Jacobs and had won seven US Championships out of seven but after being broken on serve twice and falling behind 3-0 in the final set, she suddenly advised the umpire that she could not continue citing a bad back. A reporter for the Associated Press called Will Grimsley wrote:

“The spectators were stunned. The newsmen were outraged. They called her a quitter and a poor sport. They accused her of depriving Miss Jacobs of her moment of glory.”

That wasn’t the only reason why their rivalry had turned so bitter; Helen Jacobs had controversially worn shorts that year at Forest Hills and Wills reputedly said that there was nothing more unflattering to the female form than shorts and that it was hard to distinguish whether the wearer was a man or a woman. It wasn’t a pleasant thing to say but it was also a very pointed comment as Wills would have known, unlike the great majority of the public, that Jacobs was gay.

Helen Jacobs and Helen Wills at Forest Hills in 1933

Helen Jacobs in her tailored shorts at Wimbledon with the Wightman Cup, 1934

Helen Jacobs in 1935

Helen Wills

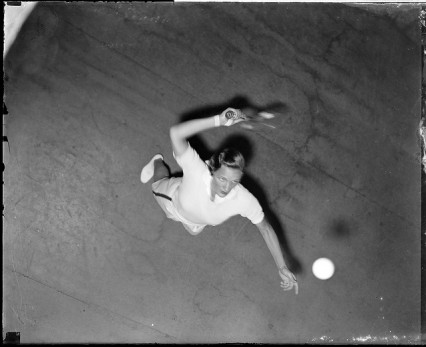

Helen Wills. Photograph by Bassano in the late 1920s

Helen Jacobs in 1933

Helen Jacobs and Helen Wills-Moody having a ‘Little Miss Poker-Face’ competition before their women’s singles finals match on Centre Court at Wimbledon, 1938

The final time the antagonistic Helens met was in the 1938 Wimbledon final. During the first set at 4-4 Jacobs strained her right achilles tendon straining to meet a passing shot from Wills-Moody. Jacobs didn’t win another game but bravely continued to the end of the match graciously, but maybe pointedly, allowing her opponent the full taste of victory in Championship final which she herself hadn’t been given five years previously. After she had won the final point Wills ran up to the net and without exchanging a smile said ‘Too bad, Helen’ after beating her for the 11th time out of 12 matches.

Helen Jacobs became a writer while still playing tennis and wrote two tennis books but also fictional works such as the novel Storm against the Wind in 1944. She served as a Commander in the US Navy Intelligence during World War II one of only five women to reach this rank. She had a life-long companion called Virginia Gurnee and she died of heart-failure in East Hampton in 1997.

Helen Wills, if not always the audience’s favourite, was undoubtedly one of the greatest ever tennis players. She died aged 92 on New Years day 1998 and left her $10 million fortune to the University of California, where she is now remembered by the Helen Wills Neuroscience Institute.

Helen Wills holding her racquet.

Women’s Tennis 1923-1938

Lots of footage of the tennis matches described above

Helen Wills defeating Elizabeth Ryan 6-2, 6-2 in 1930.