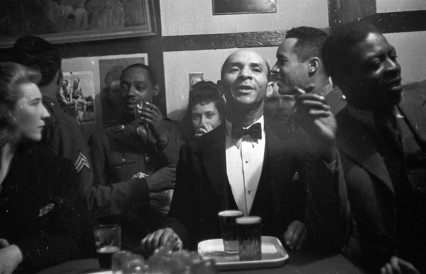

Black American soldier and girlfriend at the Bouillabaisse Club in Old Compton Street, 1943

According to Alexander Cadogan, the Permanent Under-Secretary at the Foreign Office, the cabinet meeting at Great George Street on 13th October 1942 was very disappointing:

Everyone spoke at once while PM read papers. Discussion was on a low level.

In fact the only contribution Churchill made during the whole meeting was to look up, after Viscount Cranborne, Secretary of State for the Colonies, had pointed out that one of his black Colonial Office staff had been excluded from a certain restaurant at the request of white American troops, and say:

That’s all right: if he takes his banjo with him they’ll think he’s one of the band.

Maybe not Churchill’s finest hour. The cabinet, with or without Churchill fully concentrating, agreed that it was important to respect how the US Army treated its black troops (they were completely segregated) and that it would be less problematic for all-concerned by concluding that:

It was desirable that the people of this country should avoid becoming too friendly with coloured American troops.

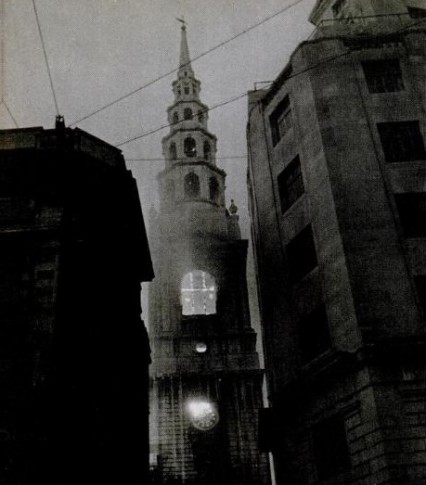

The war cabinet room at Great George Street. Protected by a five foot layer of solid concrete known as ‘the slab’. Now part of the Churchill War Rooms.

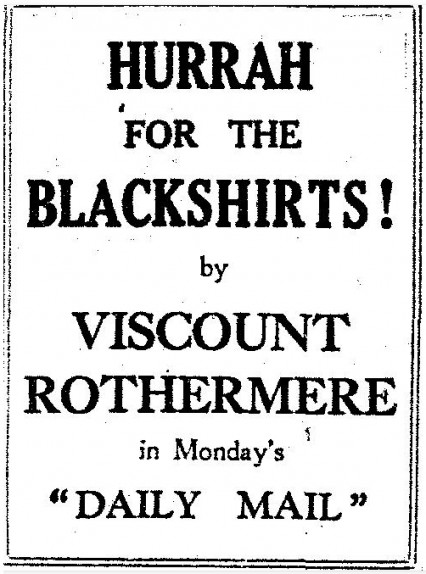

Less than a year later on September 28th 1943 the Daily Express, who had recently been running a pretty strong anti-segregation and anti-colour bar campaign, put on a show at the Royal Albert Hall that was for and on behalf of the visiting ‘coloured American troops’.

At the beginning of the evening and to the sound of rolling drums a single file of two hundred black soldiers from a segregated division of the American Air Forces’ Engineers marched onto the stage of the Royal Albert Hall on the evening of September 28th 1943. The nervous soldiers were joined on stage by Roland Hayes the renowned black lyric-tenor who had travelled to England specifically for the occasion.

Roland Hayes and the ‘Negro Chorus’ were at the prestigious venue for the debut of an orchestral work called ‘Morning Freedom’. The piece of music was described as a ‘tone poem’ set to traditional ‘negro spirituals and songs’ by its composer – the controversial communist and, as far as the mores of the day allowed, the pretty-well openly gay Corporal Marc Blitzstein.

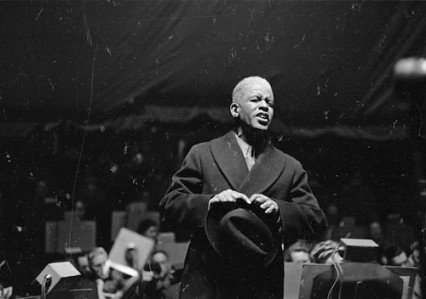

The dapper Roland Hayes performing at the Royal Albert Hall, 28th September 1943

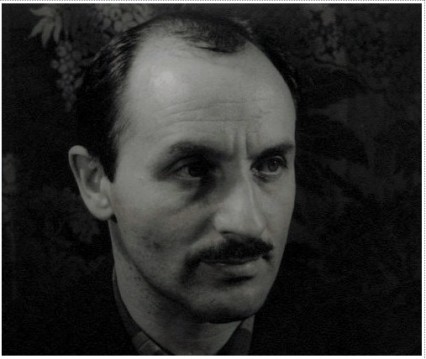

Corporal Marc Blitzstein the gay, communist American composer.

The two-hundred strong ‘negro chorus’ at the Royal Albert Hall.

The black serviceman choir was originally put together by Private McDaniel from Kansas City as a quartet to sing spirituals and hymns they would have sung at church back home. Slowly the singing group grew to the two hundred men that made up the chorus Blitzstein used for the Albert Hall concert. Private McDaniel explained to Life magazine about the soldiers’ love of spirituals:

Christianity means a lot to us dark boys. A man that can sing a good spiritual can always find his way into another boy’s heart.

members of the audience at the Albert Hall watching Blitzstein’s Morning Freedom

Roland Hayes, a son of two former slaves, was well known to British audiences of the time , although unlike his contemporary Paul Robeson, almost completely forgotten in Britain now. He had first came to London twenty three years ago. Hayes, born in Georgia, had been finding it next to impossible to find prestigious engagements in his homeland and decided to travel to Britain to further his career.

Incredibly within a year of arriving in London he was asked to give a private performance to George V and Queen Mary at Buckingham Palace on St Georges Day 1921. When Hayes arrived at the Palace, it was said that King George told his attendants: “There will be no formalities today. I shall meet Mr. Hayes man to man.” The royal recital immediately gave Hayes international prestige and he toured Britain and Europe to great success.

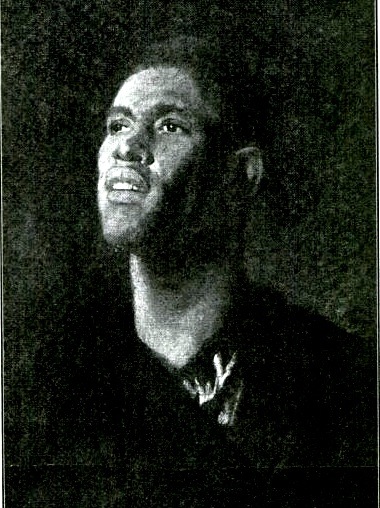

Roland Hayes painted by Glyn Philpott, 1923

Hugo Weisgall conducting American tenor Roland Hayes and the London Symphony Orchestra

The (Manchester) Guardian wrote of him:

The only really good tenor who has come along lately is the Negro Roland Hayes. His voice is genuine, pure warm and rich, and his artistic instincts are of the finest.

When Hayes visited Berlin in September 1923 he found the appreciation slightly harder to come by. Time magazine that year wrote:

To Germans, black men are “colonials”; they encountered them in the French line during the War; more recently, in the Ruhr. Learning that a member of this unpopular race was to appear publicly in their midst, Berliners were indignant. Protests were made to the American Ambassador against the “impertinence” of permitting a Negro to be heard on the concert stage, against the lèst majesté of offering musically scrupulous Berlin the tunes of the Georgia cotton-pickers.

Not entirely surprisingly, when Hayes appeared on stage, the audience started booing and hissing almost immediately. Hearing the noise the apprehensive singer suddenly decided to change his rehearsed programme and started the evening singing Schubert’s Du Bist Die Ruh. It was a German favourite and the crowd quietened almost immediately but by the end of the song, the audience, throwing their prejudice aside, were on their feet cheering and applauding the black American singer.

Roland Hayes at the Royal Albert Hall, 1943

Exactly twenty years later the British had started to bomb Berlin seemingly on a nightly basis in the hope of breaking the city’s morale. The tide in the war had changed and American soldiers were arriving in Britain in greater and greater numbers, including approximately 130,000 segregated black Americans. In 1943 the entire indigenous black population of Britain was around only a tenth of that number.

I am fully conscious that a difficult social problem might be created if there were a substantial number of sex relations between white women and coloured troops and the procreation of half-caste children.” Herbert Morrison (the Home Secretary) in a memorandum for the cabinet, 1942.

The arrival of the black American troops caused disquiet in both the US and UK governments ostensibly because of the fear of racial mixing and miscegenation. Sir Percy James Grigg, the Secretary of State for War, advised in a circular that he intended to be sent to all senior officers in the British Army:

It is necessary for British men and women…to take account of the attitude of white American citizens. British soldiers and auxiliaries should try to understand the American attitude to the relationships of white and coloured people and that difficult problems do arise when people of different races live together.

Sir PJ, as he was known, betrayed a rather hideously ignorant and patronising attitude to black Americans in his circular. ‘Mutual esteem’ indeed.

Tom Driberg, then an Independent M.P., asked the Prime Minister in Parliament to “make friendly representations to the American military authorities asking them to instruct their men that the colour bar is not a custom of this country.” Time magazine in the US reported that Driberg’s question ‘peeled the blanket of official silence off a complex and dangerous problem’. The magazine quoted eyewitness stories such as:

A pub keeper, indignant at American whites’ behavior toward Negroes, put up a sign on his bar door:

For the use of the British and of colored Americans only.

Three Negroes on a bus leaped to their feet when a white officer boarded it. Said the girl conductor, tartly:

Sit down. This is my bus and this is England.

The Prime Minister Winston Churchill thought Driberg’s question was unfortunate and

…that without any action on my part the points of view of all concerned will be mutually understood and respected.

‘Understood’ and ‘respected’ weren’t probably the first words that came to mind for a lot of people when the US military issued an horrific memorandum of advice, albeit hurriedly withdrawn, for its commanders:

Colored soldiers are akin to well-meaning but irresponsible children. Generally they cannot be trusted to tell the truth or to act on their own initiative except in certain individual cases. The colored individual likes to ‘doll up’, strut, brag and show off. He likes to be distinctive and stand out from the others.

At a cabinet meeting it was agreed that the UK should not object to the Americans segregating their troops, but they must not expect the UK authorities to assist them with this policy. “It should be made clear to the US that there should be no restrictions on the use of canteens, cinemas, pubs and theatres by ‘coloured’ troops”.

“The morale of British troops is likely to be upset by rumours that their wives and daughters are being debauched by American coloured troops”. Herbert Morrison, reporting to the cabinet, 1942.

“There are some white women in this country who feel that American coloured troops are particularly attractive and who run after them, that is a difficulty which will not be cured by keeping American coloured troops out of canteens or clubs at all”. Memorandum from Viscount Simon, Lord Chancellor, 1942.

“For a white woman to go about in the company of a Negro American is likely to lead controversy and ill-feeling, it may also be misunderstood by the Negro troops themselves”. Memorandum from Stafford Cripps, the Lord Privy Seal, 1942.

In reality this just wasn’t the case, for instance in 1944 American world heavyweight boxing champion Joe Louis was in Britain on a morale boosting tour. He decided to watch a film but when he entered the cinema, he was told by the manager that there was a special section in the cinema which was reserved for black troops. Louis recalled:

Shit! This wasn’t America, this was England. The theatre manager knew who I was and apologized all over the place. Said he had instructions from the Army. So I called my friend Lieutenant General John Lee and told them they had no business messing up another country’s customs with American Jim Crow.

Marc Blitzstein, determined to do his bit in the fight against fascism, joined the US 8th Army Air Force after the USSR entered the war. Stationed in London he was also the music director of the American Broadcasting Station (eventually to become ABC) and continued to compose.

Before the war he had written a musical that had made his name – The Cradle Will Rock. The show was about striking steel-workers and produced by the young Orson Welles (the success of the productions inspired him to start the Mercury Theatre).

Marc Blitzstein with Leonard Bernstein at the piano in 1943

Now Blitzstein was in London he became incensed about the blatant oppression and segregation of the second-class soldiers that made up the so-called ‘colored units’. Black soldiers, whatever their rank, were always seen as subservient to white officers. The segregation of the black soldiers inspired the composer to write Morning Freedom and he dedicated it to their struggle.

The ‘Negro Chorus’ performing ‘Morning Freedom’.

Roland Hayes

At the Royal Albert Hall Morning Freedom was performed for the first time. McDaniel’s chorus was accompanied by the London Symphony Orchestra conducted by Sergeant Hugo Weisgall. The choir with the help of Roland Hayes also sang Blitzstein-arranged spirituals such as Go Down Moses and In the Sweet By and By. They also sang Ballad for Americans a political song made famous by Paul Robeson.

At the end of the concert the audience of over five thousand stood up and ‘enthusiastically acclaimed’ the performance. The Evening Standard wrote:

The most remarkable ceremony I have ever attended in that famous meeting place. The audience was in ecstasy…it was impossible to believe that the chorus had not sung together before in public

The Times was equally as effusive:

without parallel in the long and varied sequence of events that have taken place within its encircling walls.

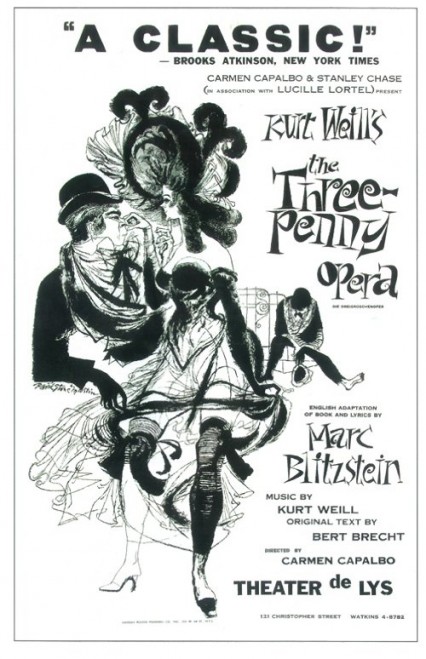

Marc Blitzstein carried on composing after the war but in terms of commercial and popular success it was Blitzstein’s 1954 adaptation and translation of Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht’s Threepenny Opera that made the greatest impact. Incidentally, due presumably to the lack of threepenny bits in America, Blitzstein had toyed with calling the musical ‘The Two-Bit Opera’ or the ‘Shoestring Opera’.

The production, featuring Weill’s widow Lotte Lenya recreating her original role, albeit this time in English, enjoyed one of the longest runs in New York’s theatre history. By the end of the decade Blitzstein’s version of Mack the Knife became a huge hit for several singers including, of course, Bobby Darin, Louis Armstrong and Ella Fitzgerald.

In 1958, Blitzstein appeared before the House Committee on Un-American Activities where he admitted his membership of the Communist Party although he had left in 1949. However he refused to name names or co-operated any further.

In January 1964, holidaying in Martinique, and after a session of heavy drinking, Blitzstein picked up three Portuguese sailors. Pretending to initially respond to his sexual advances they eventually robbed him, beat him and stripped him of all his clothes. The injuries didn’t seem serious at first but he died the next day of internal bleeding on January 22nd 1964.

American serviceman were paid up to five times the amount their British equivalent earned.

On July 26, 1948, President Harry Truman signed Executive Order 9981. It at last integrated the military and ensured the equality of treatment and opportunity for black soldiers. It also made it illegal in military law to make a racist remark. Unsurprisingly the American army dragged its feet and the proper desegregation of the military was not complete for several years and in fact persisted during the Korean War. The last all-black unit in the US Army wasn’t disbanded until 1954.

American public information film called ‘Know Your Ally – Britain’. Apparently the island is as crowded as a sardine tin.

Nat ‘King’ Cole – In the Sweet By and By

Roland Hayes – Du Bist die Ruh