Pauline Boty on her bed in 1963.

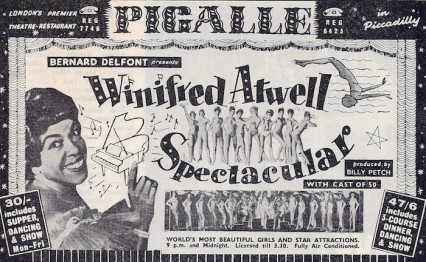

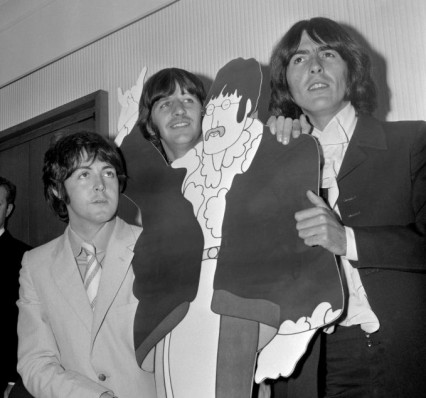

At 2.00pm on Monday, 8 July 1968, and nine days before the world premiere, three of the Beatles arrived at a press-screening of Yellow Submarine. It was at the 102-seat cinema situated inside Bowater House in Knightsbridge, a massive post-war office block that was distinctly ‘carbuncular’ in appearance. It had been built a decade before in 1958 by the developer Harold Samuel for the Bowater-Scott Corporation the world’s largest newsprint company, and the building completely dominated the adjacent Scotch Corner junction.

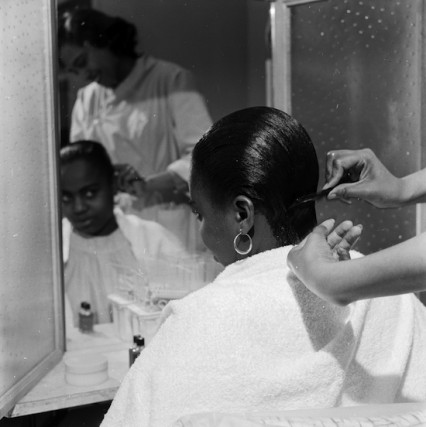

John Lennon was the Beatle missing at the film-screening, and he was almost certainly at home completely stoned, although Paul, George and Ringo jokingly posed for the photographers with a life-size cardboard cutout of John’s cartoon character. Harrison told reporters that because of the bad reviews of the Magical Mystery Tour the previous year, the Beatles from now on would only appear in animated form. He then tried to avoid answering a question about the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi but McCartney interrupted and said that the episode was just ‘a phase’ and that ‘we don’t go out with him anymore’.

The Beatles at Bowater House in 1968. Spot who’s missing.

Three hours later the three Beatles were driven to the EMI studios at Abbey Road where they started another version of Ob La Di Ob La Da (there had already been three days of aborted sessions). At the studio, according to The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions by Mark Lewisohn, they were joined by Lennon:

“John Lennon came to the session really stoned, totally out of it on something or other, and he said ‘Alright, we’re gonna do Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da’. He went straight to the piano and smashed keys with an almighty amount of volume, twice the speed of how they’d done it before, and said ‘This is it! Come on!’ He was really aggravated. That was the version they ended up using.”

Bowater House in Knightsbridge in 1958.

Bowater House, except maybe in size, was not an impressive building and now would be seen as typical of so much unimaginative post-war architecture springing up around London during the fifties and sixties. It is unsurprising that thrift and speed often took precedence over quality and taste when so much of the capital still had to be rebuilt after the war.

In 1959, Mies Van der Rohe was in London and in a taxi on his way to receive a gold medal from the Royal Institute of British Architects. His fellow passenger Erno Goldfinger pointed at the newly built Bowater House and said, ‘This is all your fault.’ To which Van der Rohe responded pointedly, “I was not the architect of that building.’

Just after Bowater House had been completed in 1958, and not half a mile up the road in South Kensington, a twenty year old Pauline Boty began her first year at the Royal College of Art in South Kensington. Boty was at the School of Stained Glass but had originally wanted to study painting but dissuaded because, especially as a woman, it was far harder to be accepted at the RCA as a painter. It’s worth noting that when in 1962 the specially designed, and much-complimented, RCA building opened next to the Royal Albert Hall there were no women’s toilets in the staff room. It was a man’s world, even at art college.

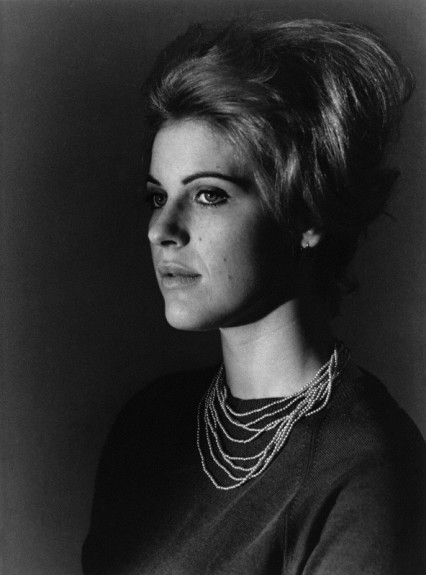

Pauline Boty in 1958, the year she started at the Royal College of Art.

Not long into Pauline’s first term, the rector of the RCA, Robin Darwin (the great grandson of Charles Darwin incidentally) invited an ex-RAF pilot called Ian Nairn to give a talk about architecture. Nairn had made his name with a special issue of the Architectural Review called ‘Outrage’ a few years earlier in 1955. The point of his lecture was that bad buildings weren’t just disappointing but should be seen as unacceptably offensive. He persuasively got his point across and the Stained-Glass students despaired that the general public were seemingly indifferent to what was being built around them.

After the lecture Nairn and a handful of Stained Glass first-years namely Pauline Boty, William Wilkins, Ken Baynes and Brian Newman, but also some other RCA students such as Barry Kirk, Ken Roberts, Ron Fuller and Janet Allen, thought it was about time something was done and Anti-Ugly Action was born.

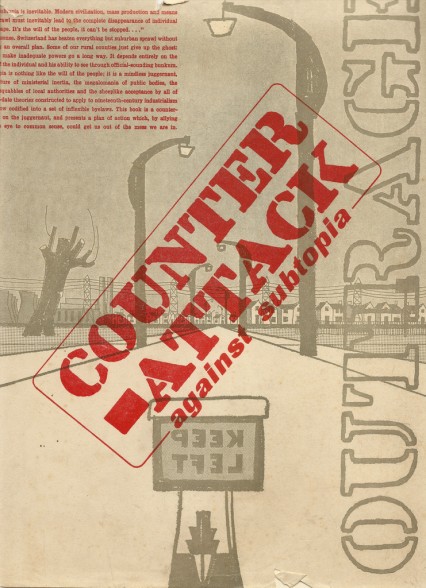

Ian Nairn’s Outrage published in 1955.

On Wednesday 10th December and choosing not to travel too far across the capital to make their point, not that they particularly needed to and they were art students after all, the Anti-Ugly Action or the Anti-Uglies as they quickly came to be known, marched down towards Knightsbridge Green accompanied by a bass drum beating out a funereal rhythm with everyone shouting ‘Outrage, Outrage, Outrage’. On the way they stopped outside the recently completed Bowater House and clapped, waved and gave it three cheers in appreciation of the architecture. It’s difficult to understand today their appreciation of this building as even Ian Nairn, who was actually on the demo that day, would later describe Bowater House as:

A curate’s Egg. Walls with a good deal of trouble taken over the materials and proportion, yet a roofline which is laissez-faire at its worst. This perhaps should be the average. Alas, it is far above it.

Bowater House, 1965.

The view through Bowater House from the Hyde Park side.

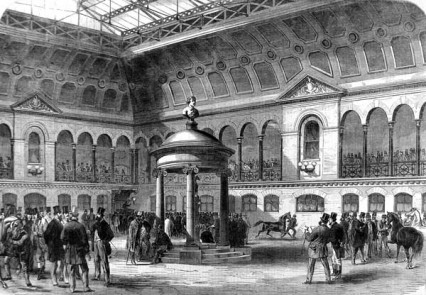

Their first target was Caltex House designed by a subsidiary of the Alliance Assurance Company and completed the previous year in 1957. It occupied the site of what used to be Tattersall’s auction yard which had been in the area since 1766 when Richard ‘Old Tat’ Tattersall (presumably that’s where the phrase comes from) opened his auctioneers near Hyde Park Corner, then on the very outskirts of London. As a nod to the horses that once were traded at Tattersall’s, Caltex House was adorned by a sculpture of horses called Triga by Franta Belsky and made of metal-coated reinforced concrete.

Caltex House in 1958.

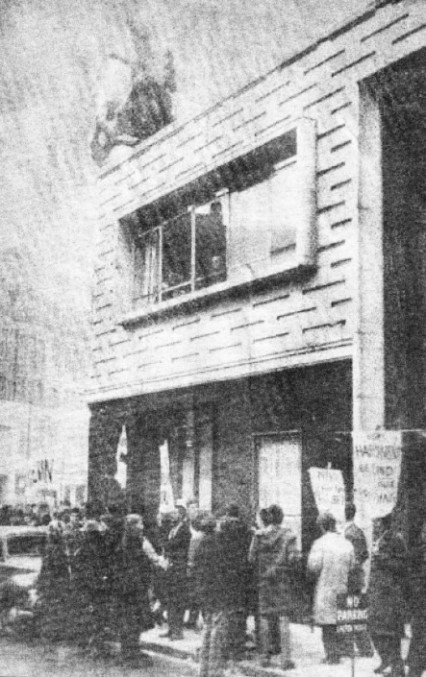

The Anti-Uglies outside Caltex House, December 1958.

Caltex House on Knightsbridge Green, 2013.

Tattersall’s auction yard in 1865.

Bidding in progress at Tattersall’s horse auctions in November 1938.

The second part of the Anti-Uglies’ protest that day, called ‘Operation Two’, was outside Agriculture House at 25-27 Knightsbridge. It was a monumental neo-Georgian building that was the headquarters of the Farmers’ Union and built just a few years previously in 1954. It had replaced two properties both badly damaged during the war. At number 25 a prestigious London showroom of the designer Betty Joel had once stood. The building featured a modernistic shopfront of plate glass and coursed slate and ‘shiprails’ to the first floor windows. Next door, at number 27 had been the once prestigious Alexandra Hotel which the journalist and former London editor of The Manchester Guardian James Bone, in 1940, once recorded as ‘that prim hotel of suites in Knightsbridge … probably the last hotel in London where country people still come up “for the season”’.

Betty Joel showroom at 25 Knightsbridge, 1938. She produced lavish interiors for the offices and boardrooms of Coutts Bank, Claridges, the Daily Express and Shell.

Agriculture House

Knightsbridge in 1958 with Agriculture House in the distance. This is what it would have looked like when the Anti-Uglies were protesting outside.

The Caltex Building and Agriculture House were both built in parts of Knightsbridge that had suffered badly from bomb damage. At around 12.30am, 11 May 1941 the Alexandra Hotel was hit by a single high explosive bomb. It smashed straight through five floors of the opulent hotel and detonated in the heart of the building resulting in twenty-four fatalities and sixteen people seriously injured. Three years later in 1944, and up the road at Knightsbridge Green, a V1 missile exploded which left 29 casualties and 6 dead.

Between 1955 and the time of the Anti-Uglies protest new large office buildings had changed the appearance of the Knightsbridge Green area considerably. Although the LCC wanted to go further, much further. There were already plans submitted where the road junction at Scotch Corner was to be turned into a huge gyratory-system comparable to those at Marble Arch and Hyde Park Corner. The massive roundabout would have been overlooked by three tower blocks more than 400 ft high.

The relatively diminutive 308 ft high Basil Spence-designed tower that is part of the Knightsbridge Barracks in Hyde Park that exists today was originally designed to just be part of a ‘visually appealing group’ along with the LCC tower blocks. By the late sixties, in the light of changed economic conditions and fashion, the great majority of the plans, which would have destroyed much of Knightsbridge, were thankfully dropped.

The day after the Anti-Uglies’ protest The Times talked not of the terrible architecture but of the students’ unusual clothes, describing them wearing:

“Lumpy coats, blue jeans, hats like tufts of gorse, and one case, green boots.’

However a more supporting John Betjeman wrote in the Daily Telegraph:

Art is coming into its own again after the worship of science and economics. What is more important, the art of architecture is at last coming in for the public notice it deserves.

It wasn’t just the newspapers and television reporters who found the protest difficult to understand, members of the watching public were confused too. Caltex house featured a retail parade of six shops, one of which was Bazaar, Mary Quant’s second shop. During the demonstration a perfectly dressed shop-assistant-cum-model emerged from the recently opened boutique to ask what the chanting was all about. She could only respond to the Anti-Uglies answer with ‘but you’re all so ugly yourselves!’

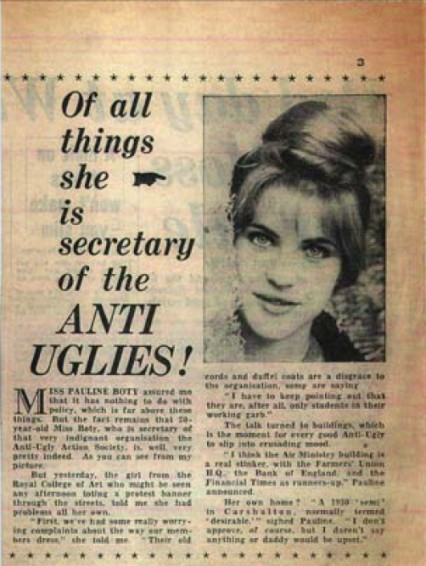

Daily Express, March 16th 1959.

This was patently untrue, at least as far as Pauline Boty was concerned, and she appeared in the Daily Express a few months later on March 16th 1959 in the William Hickey column next to a headline: ‘Of all Things She is Secretary of the Anti-Uglies’. Boty told the Express:

I think the Air Ministry building is a real stinker, with the Farmers’ Union HQ, the Bank of England [a huge curved block along New Change by Victor Heal, which has now been demolished] and the Financial Times as runners-up.’ And her own home? ‘A 1930s semi in Carshalton , normally termed “desirable”, sighed Boty. ‘I don’t approve, of course, but I daren’t say anything or daddy would be upset.

The photograph accompanying the article was taken by Lewis Morley, then a frustrated painter, but who would famously go on to take the iconic picture of a naked Christine Keeler astride a backwards-facing chair. He recalled:

Someone decided Pauline should be photographed to publicise Anti-Ugly Action. I took several photographs of her that day, showing a blonde, vivacious girl, filled with joie de vivre. She was stunning, a major factor in why the article found a place in the Express.

Pauline was also interviewed at one of the protests by the BBC TV local Friday evening news roundup ‘Town and Around’ and was asked: ’ What’s a pretty girl like you doing at this sort of an event?’. Instead of kicking him in the shins, Pauline smiled and said that the building was an expensive disgrace. The interviewer said that he had been told that it was very efficient inside, ‘We are outside’ she countered.

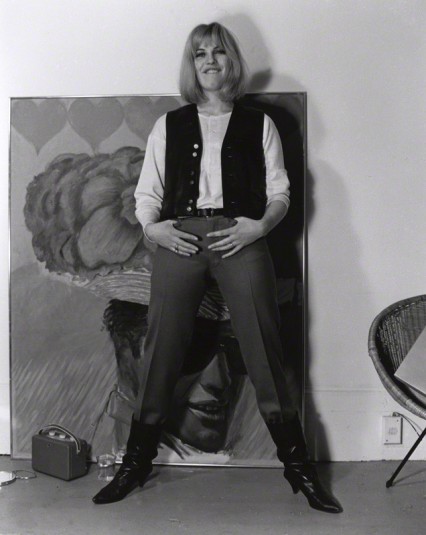

Pauline Boty by Michael Ward

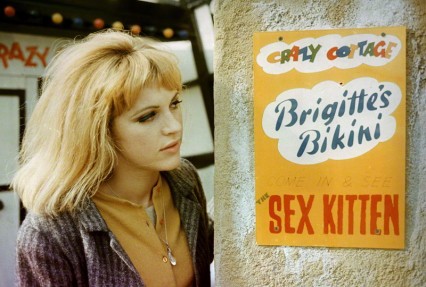

At the time of the Anti-Ugly protests Pauline Boty was twenty years old, born in 1938 in suburban Carshalton in Surrey. The youngest of four children she won a scholarship for the Wimbledon School of Art when she was sixteen and went on to study there despite her father’s very strong reservations about her choice of career. Due to her good looks, personality and blonde hair her friends at the college called her the ‘Wimbledon Bardot’.

Brigitte Bardot was already famous to the British public, she had appeared in Doctor at Sea in 1955 and had actually already made seventeen films when ‘And God Created Woman’ made her an undoubted international star in 1957. It was directed by her husband Roger Vadim who had been Bardot’s lover since she was fifteen: “she was my wife, my daughter, and my mistress,” he once wrote. Although by the time the film was released, she was none of those things, and Bardot was living with her co-star Jean-Louis Trintignant and having an affair with the musician Gilbert Bécaud. Boty jokily enjoyed the comparison with the French actress and Charles Carey, Boty’s tutor at time, once recalled a younger student going up to her in the canteen at Wimbledon and asking her why she wore so much red lipstick: ‘ ‘All the better to kisssss you with,’ she said, and chased him out of the room.’

In 1957 one of Boty’s paintings were shown at the Young Contemporaries exhibition alongside Robyn Denny, Richard Smith and Bridget Riley and the following year she was accepted at the RCA. Although studying Stained Glass, Boty continued to paint at her student flat and in 1959 she had three more paintings selected for the Young Contemporaries exhibition.

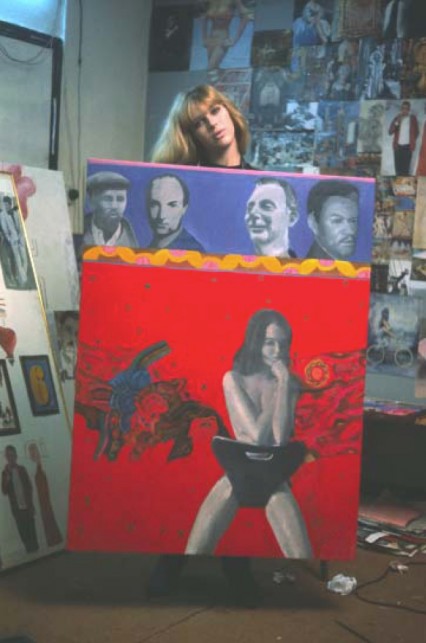

Pauline Boty in front of a poster for the Blake, Boty, Porter, Reeve exhibition. Photograph by John Aston.

The two years after her graduation were perhaps Boty’s most productive, she had started to develop a personal ‘Pop art’ style by now. Her first proper group show ‘Blake, Boty, Porter, Reeve was held in November 1961 at the A.I.A gallery at 15 Lisle Street (where the restaurant Fung Shing is now) and may have been the first proper British Pop Art show, although the word ‘pop’ wasn’t used in contemporary reviews.

Pauline Boty with her painting ’5,4,3,2,1″ Which featured Cathy McGowan and the words “Oh for a Fu…” Boty was actually a dancer on the early episodes of the show.

In 1962 Boty appeared in a film that was part of the BBC TV arts series Monitor. It was directed by Ken Russell and called Pop Goes the Easel, originally the title of a 1935 Three Stooges film. As well as Boty, it featured the artists Peter Blake, Derek Boshier and Peter Phillips and is now an important contemporary description of the relatively short-lived British ‘Pop Art’ movement. It was actually the first British documentary to use popular music as a soundtrack and the James Darren song’ Goodbye Cruel World’ used over shots of the four artists enjoying themselves at Bertram Mills Circus inside Olympia at the beginning of the film was also the title of one of Pauline’s recent collages featured at the AIA gallery the previous November. Boty said in the film:

It’s a horrible thing when people just look at my paintings and walk away and that’s it. I’d like my things to relate to everybody in the end. Things like beer cans may become a new kind of folk art; they’re like paintings on pin-tables: something else that people haven’t really looked at before.

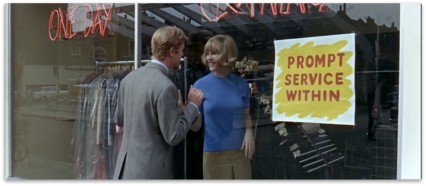

Peter Blake and Pauline Boty from Pop Goes the Easel. 1962.

Pauline from Pop Goes the Easel.

Pop Goes the Easel by Ken Russell for the Arts series Monitor in 1962.

The Wimbledon Bardot. 1963.

The fashion designer Ossie Clark but then an RCA student wrote about Pauline in the summer of 1962:

The first time she noticed me, sunbathing in her bikini bottom sprawled out in the garden. Philip Saville was her current chap, beau lovers by the score. Freckles, innocent blue eyes, lips so full, a look direct eyeball to eyeball, melt away like Tom and Jerry heavy as mercury down a drain, or foolish as I did then – What subject should she paint? I’d suggested flags of the major powers, (Derek Boshier, Dick Smith, Peter Blake) China, Russia, America. ‘Naa! S’bin done!’ Green as the grass we lay in corn, in sunlight, as the storm clouds lift the golden rays from her smile. Those lips I was eventually to kiss, so soft like crying tears absorbed into a down pillow, maudlin, too pretty. Always swanking.

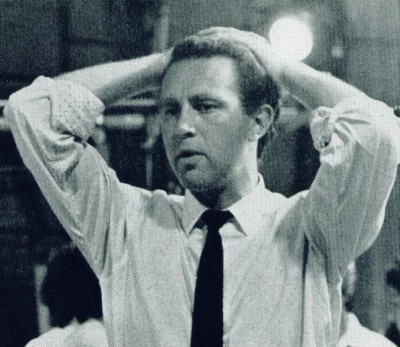

Philip Saville, mentioned in Clarke’s diary, was a married television and theatre director who usually turned his leading actresses into girlfriends. This time, however, it was the other way round and he encouraged Pauline to act, much to the dismay of many of her friends and art college contemporaries who thought that she should concentrate on her art. She appeared in television plays directed by Saville and appeared on stage at the Royal Court in a play called Day of the Prince by Frank Hilton.

Phillip Saville.

In January 1963 Saville directed a play broadcast on the BBC called the Madhouse on Castle Street which featured Bob Dylan’s first British television appearance as an actor and singer and indeed it was his first trip outside the USA. Phillip and Pauline picked Dylan up from London Airport and he stayed at Pauline’s flat for four days. As was the BBC’s wont, the play is of course wiped now but Dylan was apparently too stoned to remember his lines as Bobby the Hobo and could only sing two of his songs.

It is said that the relationship between Julie Christie and Dirk Bogard in John Schlesinger’s film Darling was partly based on Boty and Saville’s love affair. Ironically Boty would later herself audition for the role eventually played by Christie in the rather dated film.

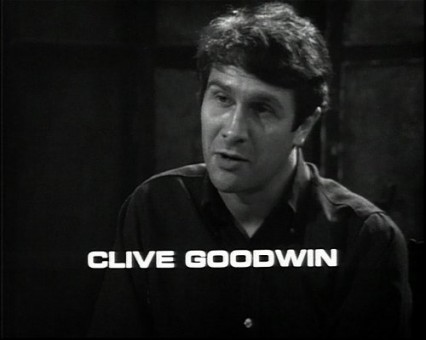

In June 1963 Saville introduced Boty to a friend of his, the left wing actor and writer Clive Goodwin. Ten days later Pauline sent Saville a telegram which was opened by his wife fearing an emergency, it read: “By the time you read this I will be married to Clive Goodwin. Please forgive me.” . Boty described her new husband in an interview with the writer Nell Dunn (who personally thought Goodwin too dull for her) as:

the very first man I met who really liked women, for one thing – a terribly rare thing in a man…I mean here was someone who liked women and to whom they weren’t kind of things or something you don’t quite know about – and because you kind of desire them they’re slightly sort of awful, because they bring out the worst in you , this funny sort of puritan idea, sort of Adam and Eve and everything.

Pauline Boty in front of her painting of Jean Paul Belmondo in 1964. Photograph by Lewis Morley.

‘Scandal’ – Pauline repays Lewis Morley, using his already famous image of Christine Keeler. 1964.

Pauline Boty, by Michael Seymour, 1962

Pauline Boty by Lewis Morley, 1963.

In June 1965, two months before she filmed a bit part in the film Alfie, Boty found out she was pregnant. During a prenatal examination, however, she was found to be suffering from malignant lymphatic cancer. She refused an abortion but also chemotherapy that may have harmed her baby. Her daughter, who was called Boty Goodwin (so she would always have her mother’s name) was born in February 1966. Too ill to cope with a baby Pauline looked after her for just four days before her parents took over responsibility of their granddaughter.

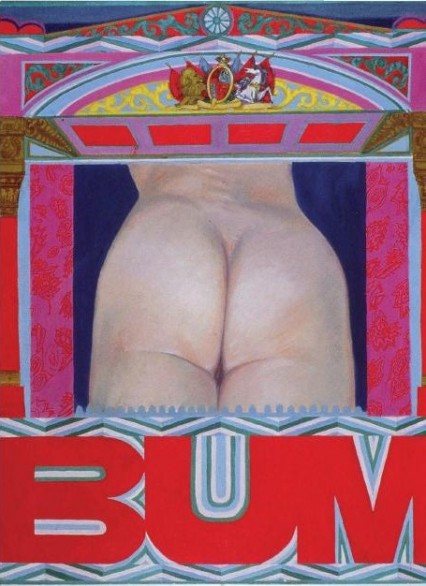

Pauline Boty’s last painting was entitled Bum, dated 1966, and would have been completed not long before she died. Kenneth Tynan had commissioned it during early preparation of his erotic revue Oh! Calcutta!

Pauline in an uncredited scene in Alfie. She was already pregnant and knew she had cancer when she filmed this scene.

Mr Pauline Boty, Clive Goodwin.

Goodwin was devastated and never married again. In November 1978, he flew to Los Angeles for various business meetings, including one at the Beverly Wilshire hotel, where he met with Warren Beatty (who was living at the hotel at the time) to discuss the script for Beatty’s upcoming film ‘Reds’. The next day, Goodwin, who had complained about a headache earlier, began vomiting in the hotel foyer before falling unconscious. The clerk and a security guard assumed he was drunk and called the police, who handcuffed him, hauled him outside and took him to the Beverly Hills police station. Goodwin died later that night of a brain haemorrhage, alone in the cell, likely never regaining consciousness.

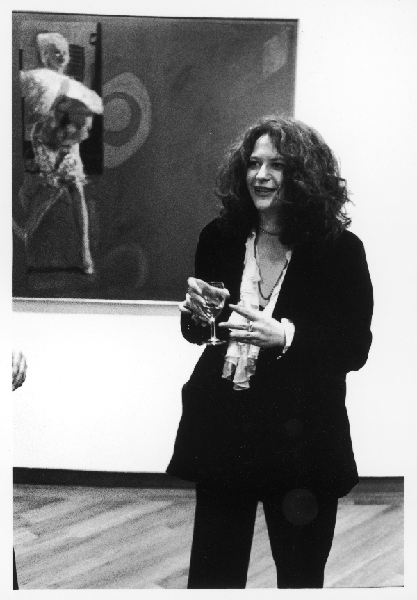

After her death Pauline Boty’s paintings were stored way on her brother’s farm and were almost thrown away more than once. For someone so well known in the art-world in the early sixties Boty and her work were almost completely forgotten. In the early 1990s the art historian David Mellor watched Pop Goes the Easel and wondered what had happened to Boty’s paintings. He tracked them down and some were exhibited in a 1993 Barbican exhibition called The Sixties Art Scene in London. Boty Goodwin, who was now at art college in Los Angeles, came to the Private View.

Incredibly, the Barbican show was the first time Pauline Boty’s work had been exhibited since she had died. Time Out included in their review of the exhibition:

Boty’s paintings shower with critical blows the macho stance of Pop.

Boty Goodwin at the Barbican exhibition in 1993.

Boty Goodwin had been brought up initially by Pauline’s parents but from the age of five by her father. She was eleven when Goodwin died and she moved back to Carshalton for the next few years. Boty eventually moved to Los Angeles in the late 1980s where, following her mother’s career, she went to Cal Arts. Unfortunately the Boty/Goodwin family tragedies still continued and in 1995 she died in her studio of a heroin overdose. She was only 29.

Over fifty years after the protests it’s interesting to look at the buildings in Knightsbridge that upset the Anti-Uglies so. Agriculture House, never a particularly popular building, was eventually demolished in 1993 for two separate properties that architecturally don’t seem to be much of an improvement, but are of a size more respectful of the area. Along with its equine sculpture celebrating ‘old Tat’ and his auction yard, Caltex House still stands and is still stodgily unexceptional and dull as when it was built, despite a facelift in 2001.

One Hyde Park overlooking Scotch Corner, 2013.

For some reason the One Hyde Park security man didn’t want photographs taken from the Knightsbridge pavement. 2013.

Jacob Epstein’s last sculpture ‘Rush of Green’. Now moved round the back of the building. 2013.

Bowater House, the building that the Uglies cheered as they walked past, was demolished in 2006 without too many people mourning its loss at the time. It’s replacement One Hyde Park was called by its once idealistic architect Lord Rogers, “a 21st-century monument” – although a monument to what no one really knows, but it seems to be some kind of celebration of the ostentatious ultra-rich and the ever-growing widening gap between the rich and poor in London. Two years ago in 2010 at the height of the credit crunch a penthouse flat in the building sold for £140 million.

Somehow One Hyde Park has managed to make people remember Bowater House almost fondly. Firstly for it’s opening in its centre that enabled anyone to drive or walk though onto Hyde Park, and secondly the sculpture ‘Rush of Green’ placed in the centre of the road for everyone to see. It was the last work by the sculptor Jacob Epstein and he was still putting the finishing touches to it on the day he died in 1959. Rush of Green has now been placed round the back of the buildings by a small road that leads to Hyde Park, although it’s cleverly designed to look private so hardly anyone uses it.

If Pauline Boty was alive today and the Anti-Uglies were still protesting I suspect that One Hyde Park, a building architecturally more suited to Qatar and Abu Dhabi than Knightsbridge, would have been first on their list.

“Outrage! Outrage! Outrage!”

Pauline Boty’s last painting from 1966. ‘Bum’.

Thank you to Eve Dawoud who introduced me to Pauline Boty and Adam Smith’s unpublished (why?) Now you see her – Pauline Boty – First Lady of British Pop. A gallery of photographs of Pauline Boty by John Aston can be found here and at the National Portrait Gallery here.