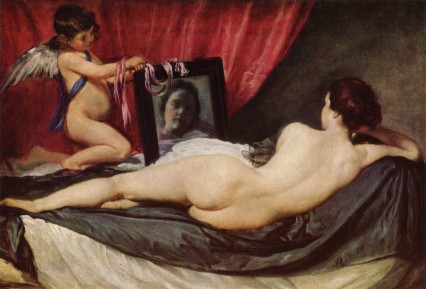

”Everything that Valasquez does may be regarded as absolutely right.” – John Ruskin

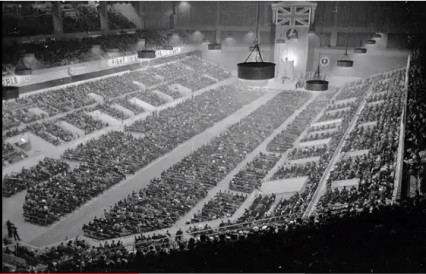

In June 1934 at an anti-fascist gathering at Trafalgar Square, a 52 year old Sylvia Pankhurst angrily denounced Blackshirt violence. It had been only three weeks since Oswald Mosley and the British Union of Fascists had held their huge staged rally at Olympia for which the Daily Mail had offered free tickets to readers who sent in letters explaining ‘Why I like the Blackshirts’.

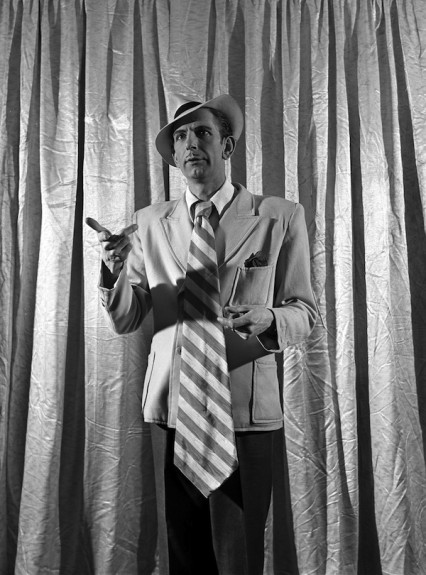

The B.U.F. rally had been designed to attract more recruits but also to impress the invited audience of politicians and journalists. Usually a stickler for punctuality, as most good fascists are, Mosley arrived on stage an hour late, but he quickly launched into a virulent anti-semitic speech shouting about ‘European ghettos pouring their dregs into this country.’

It wasn’t long before around 500 anti-fascists who had bought tickets for the meeting started shouting abuse. Mosley stopped speaking and the hecklers were picked out by roving spotlights and then ferociously attacked by black-shirted stewards. Female stewards had been trained to deal with the women hecklers by slapping instead of punching.

The Daily Express, not afraid to show where its sympathies lay, wrote about ‘reds’ gatecrashing the rally and gushed:

Inside Olympia the most amazing meeting London has seen for two decades was taking place. As soon as Sir Oswald Mosley – a remarkable black-shirted figure, picked out by the glare of two dazzling search lights, started to speak he was howled down. In the audience that had rallied to his support were hundreds of women in evening dress. As fighting broke out in all parts of the hall many started to scream, left their seats, and made for the exits. Sir Oswald’s voice amplified through twenty-four loudspeakers could be heard crying for calm. “Keep your seats! Please keep your seats.” The women were reassured and sat down. Others, of bolder spirit, were standing on chairs watching the fighting through opera glasses and laughing with excitement.

Margaret Storm Jameson, of the Daily Telegraph, presumably was sitting somewhere else in the arena and had a different view:

A young woman carried past me by five Blackshirts, her clothes half torn off and her mouth and nose were closed by the large hand of one; her head was forced back by the pressure and she must have been in considerable pain. I mention her especially since I have seen a reference to the delicacy with which women interrupters were left to women Blackshirts. This is merely untrue.

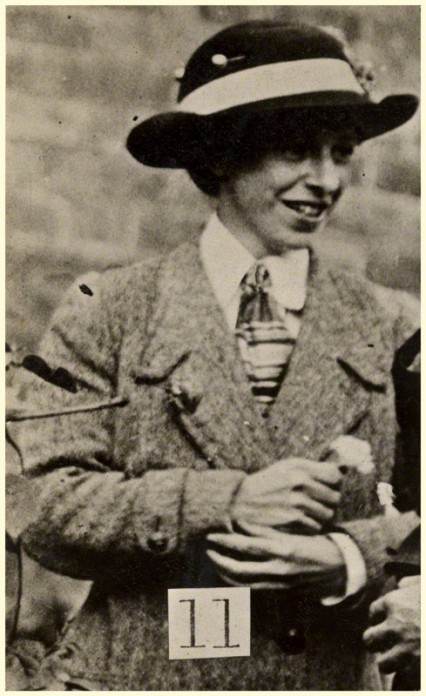

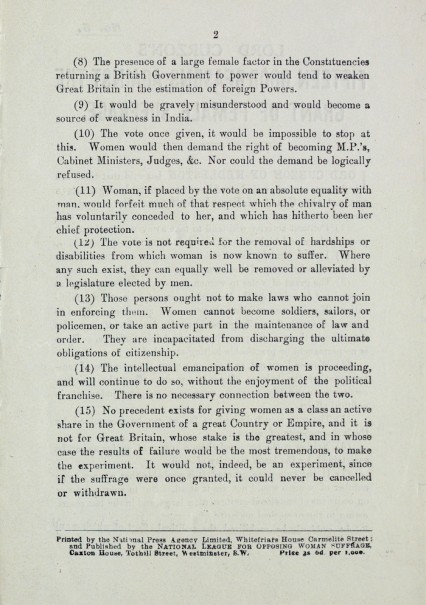

The vicious ‘Biff Boy’ blackshirt violence at the B.U.F. rally shocked many and indeed during her passionate speech to the Trafalgar Square crowd Sylvia Pankhurst particularly criticised the brutality seen at Olympia. She also warned her audience about the treatment of women in Italy saying that Mussolini had said that the “chief business of women is to be pleasing to men.” At the end of her angry speech she demanded the arrest and detention of fascist sympathisers in Britain – one of whom, notably, was her erstwhile colleague and fellow member of the Women’s Social and Political Union, Mary Richardson.

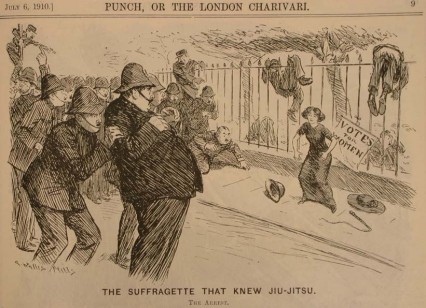

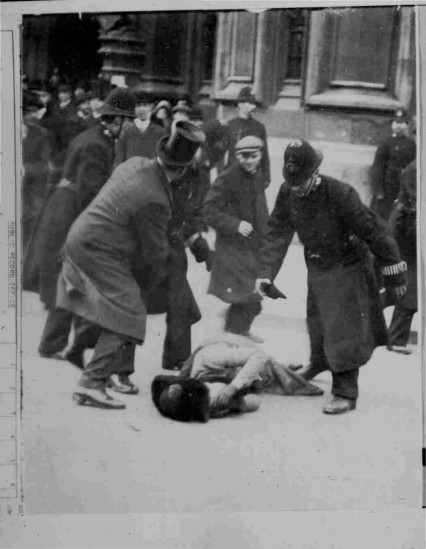

Black Friday 18th November 1910: This was the first time that Suffragette protests were met with violent physical abuse, however it was generally supported by the British population, who at the time were relatively opposed to women’s franchise. Two women died as a result of police violence, and around two hundred women were arrested.

Twenty years previously Mary Richardson had campaigned, been arrested and imprisoned with Sylvia Pankhurst in the East End of London in 1913. She had joined the Women’s Social and Political Union after witnessing ‘Black Friday’ when the WSPU lobbied parliament and were physically attacked and even sexually abused by the police.

She was arrested nine times and served several sentences in Holloway prison for assaulting police, breaking windows and arson. She was, however, particularly notorious for slashing the ‘Rokeby Venus’ in the National Gallery in March 1914. In a particularly militant period of Suffragette activity in the months preceding WW1 it is Richardson’s vandalism of Velasquez’s famous painting that is still remembered today.

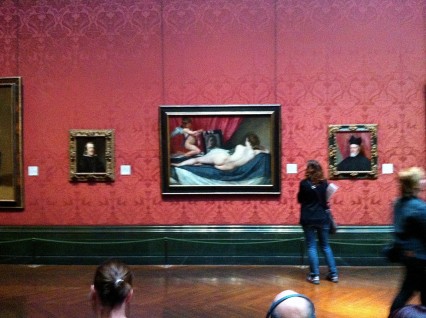

The Toilet of Venus or La Venus del Espejo, as it is more properly but rarely called, had been painted by the great Spanish artist Diego Velazquez sometime between 1647 and 1651. It is his only surviving female nude, which was an artistic direction not overly encouraged by the Inquisition in seventeenth century Spain. The painting came to England in 1813 when it was bought by John Morritt for £500 who hung it in his house at Rokeby Park in Yorkshire – hence the painting’s popular name and which it has retained ever since.

Morritt once wrote to his friend Sir Walter Scott of his “fine painting of Venus’ backside” which he hung high above his main fireplace, so that “the ladies may avert their downcast eyes without difficulty and connoisseurs steal a glance without drawing the said posterior into the company.”

In 1906, the painting was acquired for the National Gallery by the newly created National Art Collections Fund and was described by The Times as ‘perhaps the finest painting of the nude in the world’. King Edward VII greatly admired the painting and provided £8,000 towards its purchase.

The Times, struggling to find an excuse to look at a naked woman, wrote of the painting:

a marvellously graceful female figure…quite nude…neither idealistic nor passionate, but absolutely natural, and absolutely pure; she is not Aphrodite but rather “the Goddess of Youth and Health, the embodiment of elastic strength and vitality – of the perfection of Womanhood at the moment when it passes from the bud in to the flower.

When Mary Richardson walked into the National Gallery on 10 March 1914 with a meat cleaver hidden on her person, The Rokeby Venus was undoubtedly one of the most famous paintings in Britain.

Richardson had arrived at the gallery at about ten in morning and for about two hours she appeared to innocently wander around the building making occasional sketches of the paintings. No one noticed that she had also brought along a narrow butcher’s meat cleaver which was hidden from view up her sleeve held there by a chain of safety pins. She later wrote: “All I had to do was release the last one and take out my chopper and go..bang!”

As an ex-art student, she knew the gallery well and decided upon Velazquez’s ‘Rokeby Venus’. Richardson would later say: “It was highly prized for its worth in cash…the fact that I disliked the painting would make it easier for me to do what was in my mind”. She had actually submitted the idea of damaging a painting to Christabel Pankhurst some weeks before to which Christabel, eventually, wrote back saying ‘carry out your plan’. The previous year three Suffragettes had been arrested and two imprisoned for smashing the protective glass of fourteen paintings at the Manchester Art Gallery and there had been added security in exhibition spaces and galleries around the country since.

Two detectives and a gallery attendant were guarding the Rokeby Venus and a nervous and agitated Richardson almost gave up on her pre-meditated plan. At around midday one of the detectives went for lunch and the other sat down, crossed his legs and opened up a newspaper hiding the painting from his view. Richardson quietly released the cleaver from inside her sleeve and seized her chance. In an interview recorded in 1959 for the BBC, two years before she died, Richardson described what she did next:

I went and hit the painting. The first hit only broke the glass it was so thick, and then extraordinarily instead of seizing me, which he could have quite easily, because I was only a couple of yards from him. He connected the falling glass with the fanlight above our heads and walked round in a circle looking up at the fanlights which gave me time to get five lovely shots in…

The attendant rushed forward but could only slip up on the highly polished floor and he fell face first into the broken glass. Two tourists also threw their guidebooks at Richardson but eventually the detective sprang on her as she was ‘hammering away’ and snatched the cleaver from her hand. Richardson offered no resistance and as she was being taken down to the basement she quietly told the visitors she passed,

I am a suffragette. You can get another picture, but you cannot get a life, as they are killing Mrs Pankhurst.

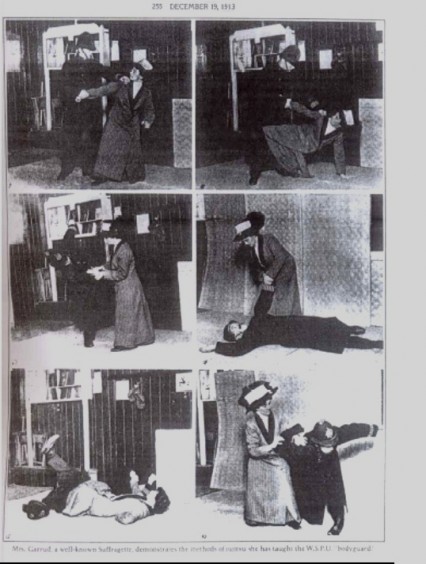

Mary Richardson had been jolted into action that morning because she had been particularly angered at the news of Mrs Emmeline Pankhurst’s arrest the night before at St Andrew’s Hall in Glasgow. Emmeline Pankhurst was at the time protected by a 25-strong bodyguard of women trained in the martial art of jujitsu. They were taught by a woman, just four feet eleven inches tall, called Edith Garrud.

Garrud had started working with the suffragettes a few years before in her own women-only training hall initially in Golden Square in Soho but later in the East End. She also taught her suffragette students how to use wooden Indian clubs which could be concealed in their dresses and used as a reply to the truncheons of the police. Garrud once said that a woman using jujitsu had ‘brought great burly cowards nearly twice their size to their feet and make them howl for mercy.’

According to The Glasgow Herald there were ‘unparalleled scenes of disorder’ when the police tried to arrest Emmeline at St Andrew’s Hall. They had been waiting for Pankhurst who had entered the building early. When she started to speak the police attempted to storm the stage but were severely hampered not only by the barbed-wire hidden in the flower decorations but also Mrs Pankhurst’s trained bodyguards.

Emmeline in ‘My Own Story’ described what happened:

The bodyguard and members of the audience vigorously repelled the attack, wielding clubs, batons, poles, planks, or anything they could seize, while the police laid about right and left with their batons, their violence being far the greater. Men and women were seen on all sides with blood streaming down their faces, and there were cries for a doctor. In the middle of the struggle, several revolver shots rang out, and the woman who was firing the revolver–which I should explain was loaded with blank cartridges only–was able to terrorise and keep at bay a whole body of police.I had been surrounded by members of the bodyguard, who hurried me towards the stairs from the platform. The police, however, overtook us, and in spite of the resistance of the bodyguard, they seized me and dragged me down the narrow stair at the back of the hall. There a cab was waiting. I was pushed violently into it, and thrown on the floor, the seats being occupied by as many constables as could crowd inside.

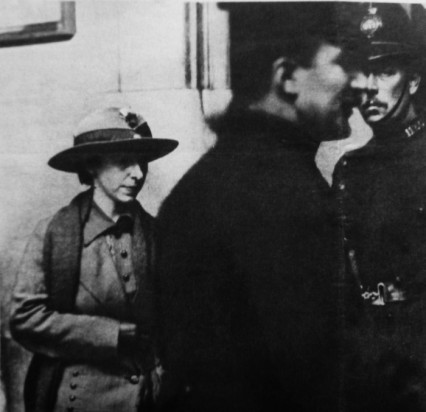

Mary Richardson would have also known that the day before Emmeline’s arrest, her daughter Sylvia Pankhurst had also been arrested. Sylvia had been travelling along the Strand on a ‘motor omnibus’ on her way to Trafalgar Square where she was to speak at a protest rally organised by the Men’s Federation for Women’s Suffrage.

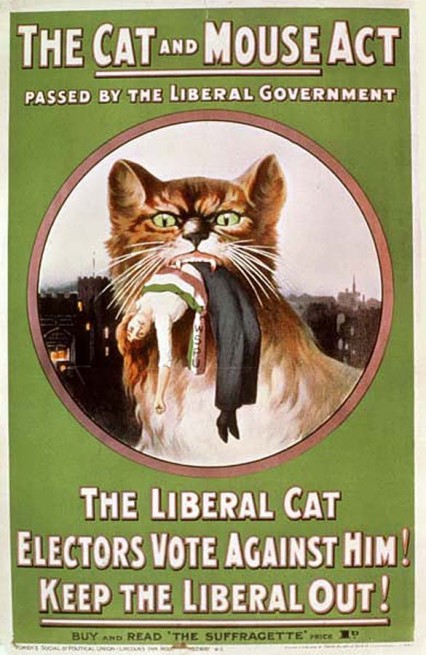

The bus had stopped outside Charing Cross Station but when Sylvia stepped on to the pavement plain clothes policeman quickly surrounded her. Like her mother she was arrested under the so-called Cat and Mouse Act. The police bundled her into the back of a taxi cab and she was sent on her way back to Holloway prison.

Sylvia Pankhurst arrested at Trafalgar Square, 1913

The following day the Daily Express reported that the news of her arrest had caused ‘intense indignation in the crowd’ waiting at Trafalgar Square, they continued, ‘Miss Patterson (sic) who acted as chairman, led a detachment towards Whitehall, waving a flag and shouting “It is deeds, not words!”.

The next day Margaret Paterson, who had continually attempted to strike policemen with a short thick piece of rope loaded at the end with lead, was fined £2. Miss Paterson said to the judge, “It had taken ten men and eight horses to arrest me. You…drag people like Sylvia Pankhurst back again to prison. You have roused a fire in the East End and ten men and eight horses won’t be enough next time!’.

It was to the Cat and Mouse Act that Mary Richardson owed her temporary freedom when she had been released the previous November after a long bout of forced-feeding. After her release she declared, ‘The worst fight on record since the movement began is now raging in Holloway’. Richardson, one of the earliest suffragettes to be force-fed had written about her experience in a 1913 suffragette leaflet, where she described a tube a yard long that ran through the nasal passage down the throat into the stomach:

Forcible feeding is an immoral assault as well as a painful physical one, and to remain passive under it would give one the feeling of sin; the sin of concurrence. One’s whole nature is revolted: resistance is therefore inevitable.

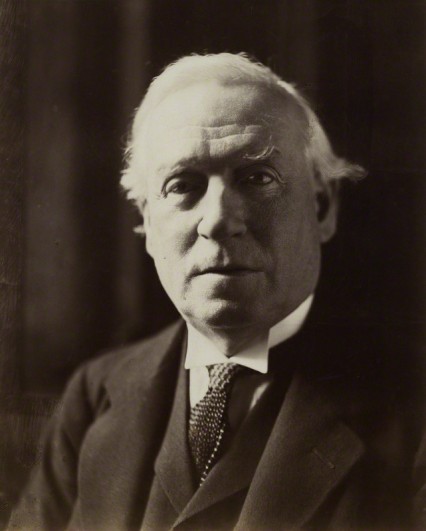

The infamous ‘Cat and Mouse Act’ was the name given to the Prisoners, Temporary Discharge for Health Act passed by H.H. Asquith’s Liberal government exactly 100 years ago in 1913. It had been hurriedly enacted to counter the growing public disquiet over the tactic of force-feeding suffragettes who were determined to continue their hunger strikes whilst in gaol. The law’s intention was that suffragettes could hunger strike to the point of emaciation, be let out of prison to recover, and then recalled to serve the rest of their sentence.

The Act’s nickname compared the government cruelty of repeated releases and re-imprisonments of suffragettes to a cat playing around with a half-dead mouse. Not surprisingly the Cat and Mouse Act had the opposite of its intention and did little to deter the more militant campaigns of the suffragettes and if anything made the public more sympathetic to their cause.

The Prime Minister Herbert Henry Asquith had been an opponent of women’s suffrage since the 1880s and his government’s implementation of the Cat and Mouse Act caused the WSPU and the suffragettes to consider the Prime Minister with particular enmity. Even women in his social circle had been privately objecting to his attitude. Winston Churchill’s wife Clementine once complained of Asquith habitually peering down cleavages, while the socialite Lady Ottoline Morrell once protested that Asquith, ‘Would take a lady’s hand as she sat beside him on the sofa, and make her feel his erected instrument under his trousers’.

A few hours after Mary Richardson was apprehended in the National Gallery she was brought up before Bow Street Police magistrates court where she was charged with maliciously damaging the ‘Rokeby Venus’ to the amount of £40,000. Richardson told the magistrate that she was amazed that anyone was willing to preside over the farce of trying her as it was the tenth time she had been brought before a magistrate in one year. He could not make her serve her sentences, but could only again repeat the farce of releasing her or else killing her; ether way, hers was the victory. The unimpressed magistrate said that he would not allow bail and committed her for trial.

Immediately after Richardson’s ‘outrage’ the National Gallery closed to the public and remained so for two weeks. The Trustees of the gallery met that afternoon to consider what steps were needed to further protect their collection. One of the trustees was Lord Curzon, the former Viceroy of India, who on his return to England had led the campaign against women’s suffrage in the House of Lords. In 1908 he had helped establish the Anti-Suffrage League of which he eventually became president.

12th March 1914. The National Gallery was closed for two weeks after the attack on the Rokeby Venus.

The press widely publicised the attack on the painting and The Times wrote:

One regretted that any person outside a lunatic asylum could conceive that such an act could advance any cause, political or otherwise.

Even the New York Times commented on the story the next day:

The British Government is getting precisely the sort of treatment it deserves at the hands of the harridans who are called militants for its foolish tolerance of their criminal behaviour. Why should women who commit assaults and destroy property be treated differently from common malefactors.

Richardson received six months for the damage she caused and later said: ‘the judge nearly wept when I was tried because he could only give me six months.’ In fact Richardson, after starting a hunger strike, only served a few weeks before she was released again.

At the outbreak of WW1 Emmeline Pankhurst suspended the activities of the WSPU and instructed suffragettes to get behind the Government and its war effort. Sylvia, opposed to the war, was horrified to see her mother and sister Christabel become such enthusiastic supporters of military conscription.

Mary Richardson published a novel called Matilda and Marcus during the war and also two volumes of poetry. In the twenties and thirties she stood several times as a parliamentary candidate for the Labour party most successfully in Acton in November 1922 when she received over 26% of the vote although losing to the Conservatives.

She joined the British Union of Fascists in late 1933 declaring in the light of her previous political experience, ‘I feel certain that women will play a large part in establishing Fascism in this country’.

Her initial post was assistant to Lady Makgill – the officer in charge of the Women’s Section whose headquarters were then based at 233 Regent Street (now the Lacoste shop next to the Apple Store) but which moved in January 1934 to 12 Lower Grosvenor Place adjacent to the grounds of Buckingham Palace. The women’s section of the Blackshirts had initially been set up by Mosley’s first wife Lady Cynthia who was known as ‘Cimmie’ and was the daughter of the anti-woman’s suffrage campaigner Lord Curzon.

Cynthia had married Oswald Mosley, then a Tory MP, in 1920, and nine months later gave birth much to the consternation of Margot Asquith, wife of former Prime Minister H.H. Asquith, who told her:

You look very pale. You must not have another child for a long time. Herbert always withdrew in time. Such a noble man.

In 1929 Cynthia was elected Labour MP for Stoke on Trent as was her husband but for the constituency of Smethwick. Two years later, Oswald, unhappy with the direction of the Labour Party formed the New Party in 1931 and subsequently the British Union of Fascists the year after that. Cynthia supported her husband in his political activities until she died in 1933 after an operation for Peritonitis following acute appendicitis. This unconditional support for her husband was generous on her part for during their marriage Oswald had an affair with both Cynthia’s younger sister and step-mother.

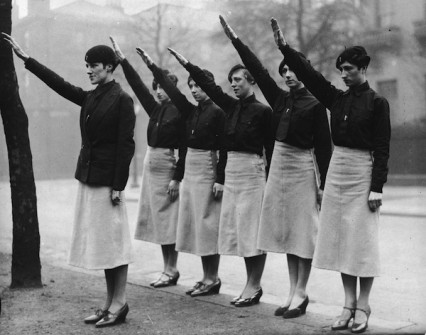

The women’s HQ was seen as crucial for nurturing female interest and recruitment levels in the BUF. The female blackshirts were encouraged to train in jujitsu and The Blackshirt newspaper reported in 1934 that it was particularly popular in London, saying ‘the ladies especially showing remarkable aptitude in this splendid form of defence so suitable to members of the “weaker sex”’.

The new main BUF headquarters, however, was practically out of bounds to women. It was called ‘Black House’ situated on the King’s Road near Sloane Square. The Fascist HQ Bulletin in 1933 stated, under the heading ‘Lady Members’, that “ladies are no longer allowed access to NHQ premises, except to attend mixed classes and concerts and at such times as may be from time to time authorised.’ Despite this ‘lady members’ made up 20-25% of the BUF membership – extremely high for a political party of the time.

It seems odd that an ex-suffragette, and such a militant one at that, would have put up with these rules, but in April 1934 Richardson became the Chief organiser of the Women’s Section. A young female BUF member remembered Richardson at the time:

The moving spirit of this [women’s HQ] was an ex-suffragette of great character. She was a fiery speaker particularly at street corner meetings and used to plaster her hair down with Grip-fix so that it would not blow about on these occasions.

Women ‘black-shirts’ giving the fascist salute. Their uniform is a black shirt and tie, beret and slightly flared grey skirts.

Richardson had replaced Lady Makgill who had resigned after being suspended for embezzlement which must have been embarrassing to her husband who had co-founded the January Club an organisation whose aim was to attract members of the Establishment to the B.U.F. cause. Mosley, however, was aware of the value of his women members. He later wrote:

My movement has been largely built up by the fanaticism of women; they hold ideals with tremendous passion. Without women I could not have got a quarter of the way.” Even the Blackshirt newspaper, stated: “Women have won the vote, but not their rightful influence in politics. Only when women represent Woman will womankind attain its rightful influence.

It was a woman who, ten years previously in 1923, created the first fascist organisation in Britain. It may well have been the first time a woman had started and led any political party in this country. She was called Rotha Lintorn-Orman and she started the British Fascisti in response to what she thought was a growing threat from the Labour party. The B.F was actually the predominant fascist organisation in Britain until Oswald Mosley created his party in 1932.

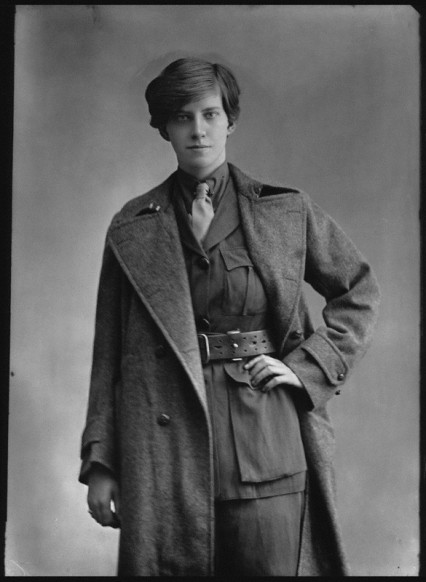

Rotha Beryl Lintorn-Orman by Bassano. The photograph is from 1916, seven years before she started the UK’s first fascist party.

On 10 November 1924 the Fascisti held a rally consisting of almost 10,000 people in Trafalgar Square most of whom, it was reported, were wearing black and silver British Fascisti badges. The Manchester Guardian reported that there was ‘a large contingent of women’. It was a man, however, the monocled Brigadier-General Blakeney, that told a cheering crowd waving black and white fascist banners and Union Jacks, that there “was a great danger that aliens should be allowed to settle in this land, over crowding the towns and taking employment from the workers.” The rally finally marched down Whitehall where several large black and white wreaths bearing the legend “British Fascists for King and country,” were left next to the four year old Cenotaph.

The British Fascisti ultimately lost members to the Imperial Fascist League and then the BUF. Lintorn-Orman, stubbornly, would have nothing to do with the latter as she considered Oswald Mosley to be a near-communist. Lintorn-Orman’s mother, who was actually the first-ever female Scout Leader, had been pay-rolling the organisation from the beginning, eventually stopping the funding amid lurid newspaper gossip about her daughter that involved alcohol and drug fuelled orgies. Rotha Lintorn-Orman died in March 1935 and her British Fascisti organisation wound up four months later. The Official Receiver reported that:

Throughout the company’s history its accounts seemed to have been kept in a lax, casual manner, and though formed to organise Fascism in the country the company appeared to have been incapable of organising itself.

In 1934, the BUF, however, now with Richardson in charge of the Women’s section, seemed organised, efficient and most of all popular. The Daily Mail on May 18 reported – ‘The recent development of the Women’s Section has been particularly remarkable’ and a few days later the Sunday Dispatch wrote:‘The women’s sections are adding – Beauty. The women and girls of Britain are flocking to the movement. Many of them are strikingly beautiful.’

November 1933: Mrs Swire a leading figure in the women’s section of the British Union of Fascists wears the new uniform of grey skirt with black shirt talks to a member of the HQ staff in London who wear all black. Mosley was afraid the women members might jokily be called the ‘black skirts’.

9th September 1934: Sir Oswald Mosley acknowledging fascist salutes from female members of the British Union of Fascists at an evening demonstration in Hyde Park.

Lord Rothermere, the owner of the Daily Mail and the Sunday Dispatch, had for several months been promoting the BUF’s cause in his newspapers. He wrote a now infamous article headlined ‘Hurrah for the Blackshirts’ in which he suggested that:

Britain’s survival as a great power will depend on the existence of a well-organised party of the Right ready to take over responsibility for national affairs with the same direct purpose and energy of method as Mussolini and Hitler have displayed.

After Sylvia Pankhurst’s speech in Trafalgar Square in June 1934 Mary Richardson responded quickly to the criticism and in the June 29 issue of Blackshirt reminded her of their shared memories of working together in Bow and being confined in Holloway at the same time. Richardson wrote:

How can she forget so easily and conveniently that the Suffragette movement, when she stood in the vanguard, was proud of its use of “force and bludgeons,” of dog whips, truncheons (carried and used by Mrs. Pankhurst’s bodyguard), stones in their multitude, and bricks and the hammers? Does she remember how for years her reply to her accusers was: “We are attacked, we must hit back!” “Paid hooligans break up our meetings; we are right to retaliate!”

Richardson continued:

I was first attracted to the Blackshirts because I saw in them the outrage, the action, the loyalty, the gift of service, and the ability to serve which I had known in the Suffragette movement. When later I discovered that Blackshirts were attacked for no visible cause or reason. I admired them the more when they hit back, and hit hard.

Mary Richardson left the BUF sometime in 1935. For what particular reason is not exactly known (her autobiography published in 1953 doesn’t mention her political activity in the BUF at all) however Lady Mosley, Oswald’s mother, described Richardson as being full of ‘dishonest inefficiency’. In 1935 Richardson spoke at a meeting of the Welwyn War Resisters – an anti-war group. The Welwyn Times on 19th December 1935 reported that she had told the meeting that she joined the B.U.F. believing that it opposed class distinction and stood for ‘equality of opportunity and pay for men and women’. She had found, however, that the organisation was riddled with hypocrisy and had been expelled in February for ‘attempting to organise a protest’.

On November 7th 1961 Mary Richardson died at her flat at 46 St James’ Road in Hastings of heart failure and bronchitis aged seventy eight. She was still remembered as the woman who had cut up the Rokeby Venus forty seven years before and most of the papers reporting on her death still used Richardson’s nickname the press used in 1914 – ‘Slasher Mary’.

If you look closely you can still see the marks caused by Mary Richardson’s meat cleaver, although the National Gallery make no mention of her vandalism on the card next to the painting. Christabel Pankhurst once said:

that ‘the Rokeby Venus’ has because of Miss Richardson’s act, acquired a new and human and historic interest. For ever more, this picture will be a sign and a memorial of women’s determination to be free.

To this day you can still see people having a close look at the painting to see if the damage is still visible. It is. Mary Richardson throughout her life used to visit the painting ‘to cheer herself up’.