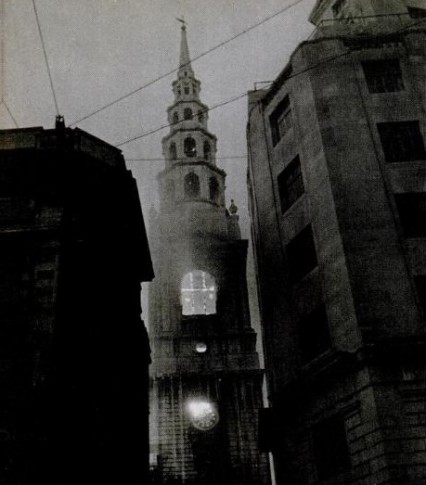

St Paul’s Cathedral, 29th December 1940

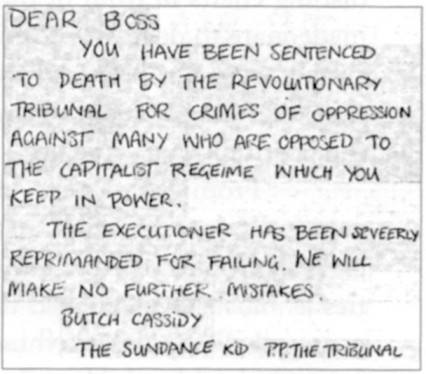

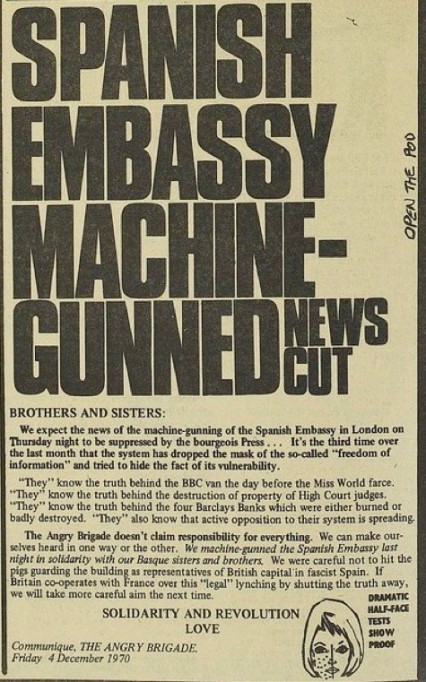

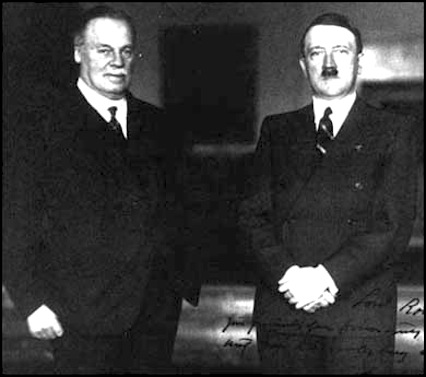

A long way from St Pauls Cathedral in Bermuda on the 26th November 1940 Harold Harmsworth, better known as Lord Rothermere – the famous proprietor and co-founder of the Daily Mail – died of what was described at the time as ‘dropsy’. Before the tired and sad old man fell unconscious he said:

There is nothing I can do to help my country now.

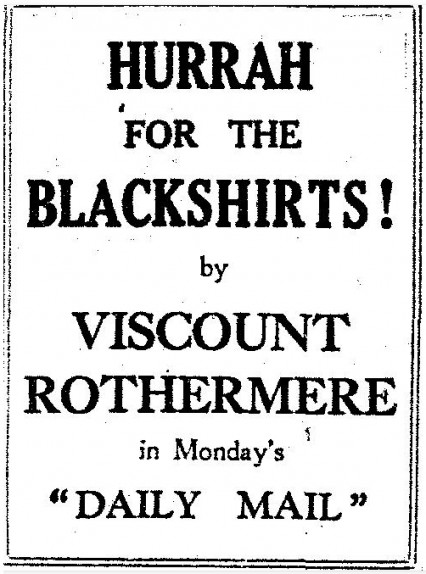

It could be said, especially in the years preceding the Second World War, that he hadn’t really done much to help his country anyway. He had been a great supporter of pre-war appeasement with Germany, he had been a fan of Adolf Hitler, and a supporter of Oswald Moseley and the British Union of Fascists, for which he infamously had the Daily Mail in 1933 proclaim:

‘Hurrah for the Black Shirts!’

Rothermere wrote that Britain’s survival could only possibly depend on ‘the existence of a Great Party of the Right with the same directness of purpose and energy of method as Hitler and Mussolini have displayed’.

Harold Harmsworth, 1st Viscount Rothermere in his civvies.

Only a month after he died the Daily Mail started to make amends. Their New Year’s edition featured one of the most memorable images of the Second World War. The right in the middle of the morale-sapping Blitz, it almost certainly helped maintain resolve in the capital.

New Year’s Eve 1940 edition of the Daily Mail.

The newspaper confidently described the photograph, maybe slightly early in the proceedings, as the ‘War’s Greatest Picture’. It featured St Paul’s Cathedral beautifully framed in some clearing smoke and dust after one of the worst Luftwaffe raids on London. The Daily Mail knew that the picture had powerful connotations and described it as:

one that all Britain will cherish – for it symbolises the steadiness of London’s stand against the enemy: the firmness of Right against Wrong.

The photograph had been taken two days earlier by Herbert Mason, a staff Daily Mail photographer at 6.30pm in the evening. It was in the middle of the three-hour raid and he’d been fire-watching on the roof of the Daily Mail building known as Northcliffe House in Carmelite Street a road situated between Fleet Street and the Thames. He later described taking the photograph:

I focused at intervals as the great dome loomed up through the smoke. The glare of many fires and sweeping clouds of smoke kept hiding the shape. Then a wind sprang up. Suddenly, the shining cross, dome and towers stood out like a symbol in the inferno. The scene was unbelievable. In that moment or two, I released my shutter.

Herbert Mason

The German bombers that evening had dropped 120 tons of high explosive but also an estimated 22,000 two pound incendiary bombs. The thermite and magnesium of these bombs burnt at 2,200 degrees Celsius with a searing, dazzling glare. Incendiaries were usually used as a way of initially lighting up a target area, this time however, they caused an extraordinary amount of destruction on their own. Their utter profusion created firestorms where the sheer heat of the fire sucked in its own wind to create huge furnaces that quickly enveloped the surrounding buildings around St Pauls.

The American Pulitzer-prize winning journalist Ernie Pyle described the scene that night:

The greatest of all the fires was directly in front of us. Flames seemed to whip hundreds of feet into the air. Pinkish-white smoke ballooned upward in a great cloud, and out of this cloud there gradually took shape – so faintly at first that we weren’t sure we saw correctly – the gigantic dome of St. Paul’s Cathedral.

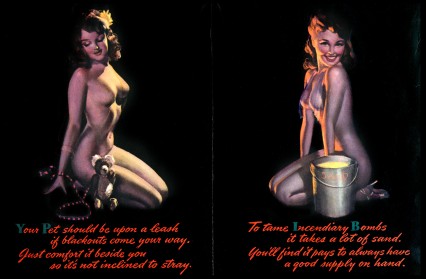

Incendiary bombs exploding

Very important information, for some reason relayed by naked women, about how to deal with incendiary bombs

Luftwaffe 1kg Incendiary bomb. It’s said that 22,000 of these fell in three hours

It was said that Air Vice Marshall Harris, later infamously known as ‘Bomber’ Harris, or even ‘Butcher’ Harris (both terms were at the time meant to be complimentary), looked upon the conflagration in the City of London and said: ‘They have sowed the wind…’. It wasn’t going to be an idle threat.

It was a particularly low tide the Sunday night of the raid and the fireman had to wade out through the mud on the side of the Thames to find water for their hoses. Despite this, and it seems almost incredible now, the fires were generally brought under control by four in the morning. The night quickly became known as the second fire of London and caused devastation in the old part of the City.

In Whitecross Street the firemen, for their own survival, had to turn their hoses upon themselves. They somehow managed to escape into a nearby railway tunnel leaving their engines to burn until they were just melted shells. That part of Whitecross Street which ran down to Fore Street at St Giles Church is now lost forever and part of the Barbican development.

The aftermath of a firestorm in Whitecross Street

Sixteen firemen lost their lives on the evening of the 29th. Eight in one go after a building collapsed on them.

A burning St Bride’s just off Fleet Street

Hundreds of buildings were completely destroyed that night including eight Christopher Wren Churches built after the original Fire of London. 160 people died including 16 fireman with 500 people injured.

Although legend has it otherwise, St Paul’s Cathedral certainly wasn’t untouched. Twenty nine bombs fell on or around the building and at one point one incendiary pierced the lead covering of the dome and after burning through some timbers fell harmlessly to the nave below where it was easily put out.

A hole in the floor of St Paul’s Cathedral

St Paul’s – the day after

Moorgate Station completely burnt out. 30th December 1940. The whole station is covered in office buildings now.

The War Cabinet convened the next morning and at Winston Churchill’s instigation it was agreed:

that the fullest publicity should be given to the damage caused in the city. As no military objectives had been aimed at, and the enemy must have known what he was attacking, there was no object in secrecy.

Thus the usual restrictions to publishing photographs were lifted and the Daily Mail printed the Mason’s photograph the next day.

A cartoon from Illingworth published by the Daily Mail on the same day, New Year’s Eve 1940

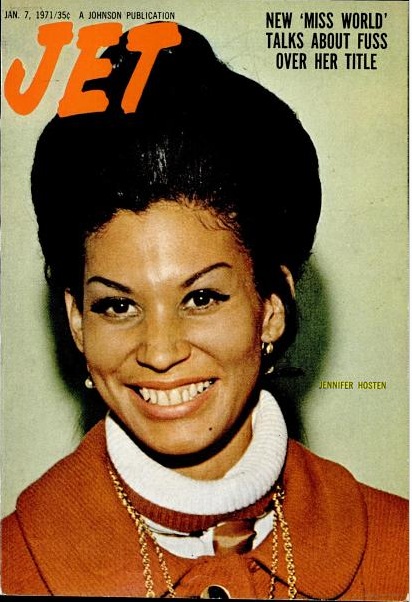

Lord Rothermere and Hitler

As mentioned previously the Daily Mail and its larger than life former proprietor, hadn’t always been helpful in the fight against the rise of Nazi Germany. In 1938, only two years before the raid that flattened the area around St Paul’s Cathedral the Daily Mail wrote:

The way stateless Jews from Germany are poring in from every port of this country is becoming an outrage.

And less than two months before the beginning of the war, Lord Rothermere sent a telegram to Hitler stating:

My Dear Führer, I have watched with understanding and interest the progress of your great and superhuman work in regenerating your country.

He added:

The British people, now like Germany strongly rearmed, regard the German people with admiration as valorous adversaries in the past, but I am sure that there is no problem between our two countries which cannot be settled by consultation and negotiation…I have always thought that you are essentially one who hates war and desires peace.

Up to a point, Lord Rothermere.

In the 1930s Rothermere had donated money to the British Union of Fascists and used his paper to openly support Oswald Moseley. However in 1933, Rothermere did write in the Mail something slightly more prescient:

The day of the warplane has come. Our desperate deficiency in these modern weapons puts the very existence of Britain in Deadly peril. Fate has never pardoned a people that refused to move with the times.

In February 1942, just over two years after the so-called ‘Second Fire of London’ the newly promoted Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Harris announced to the nation that it was time that Germany, ‘now that they have sowed the wind, reaped the whirlwind’. Which of course they did. And some.

A view of St Paul’s Cathedral in 1930

How Could We Be Wrong – Al Bowlly

You Couldn’t Be Cuter – Al Bowlly

Buy some Al Bowlly here

Buy Illingworth’s War in Cartoons here