The author Colin Wilson once said:

I had taken it for granted that I was a man of genius since I was about 13.

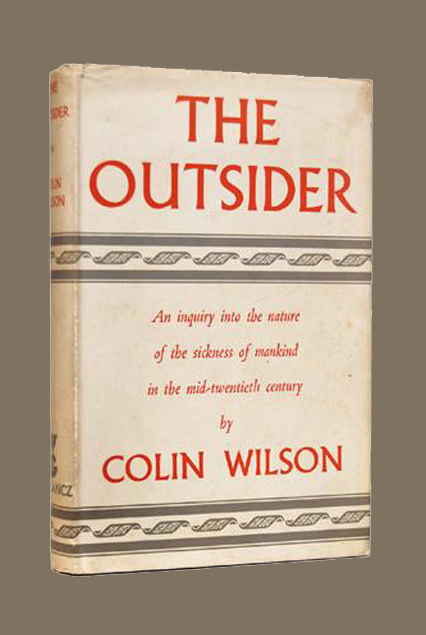

For a short few months after the publication of his first book entitled The Outsider in 1956, it seemed that the rest of the world thought so too.

abilify canada us

abilify vs generic

abilify and canada

abilify 5mg canada

prices for abilify

older cats abilify

abilify from canada

abilify and generic

abilify from canada

abilify generic teva

abilify generic name

abilify cheap canada

abilify prescription

order abilify online

abilify discount card

abilify generic names

abilify discount code

what is abilify 30 mg

abilify 10 mg pricing

i cant afford abilify

i cant afford abilify

purchase abilify cheap

update on abilify 30 mg

abilify price expensive

abilify no prescription

abilify dosage by weight

abilify prescription help

will abilify get you high

prescription drug abilify

abilify free prescription

abilify uses and strength

abilify prescription price

abilify generic equivalent

cheapest price for abilify

online prescription abilify

carbamazepine abilify 25 mg

compare abilify drug prices

abilify for 11 year old boy

abilify online prescription

can i take abilify 2x a day

price comparison for abilify

canada is generic abilify ok

who should take abilify 30 mg

problems with generic abilify

why do i need to take abilify

ok to take reglan and abilify

abilify and generic and image

abilify prescription strength

abilify without a prescription

abilify without a prescription

abilify prescription assistance

abilify 5mg canada aripiprazole

abilify and generic and picture

what is the generic for abilify

purchase abilify wo prescription

when will abilify become generic

can snorting abilify get you high

abilify sertraline generic images

abilify shortage deliver problems

picture of generic abilify tablet

ok to stop taking abilify abruptly

buy abilify without a prescription

weight and abilify and adderall xr

on line abilify prescription costs

get abilify without a prescription

what does generic abilify look like

shallow breathing caused by abilify

serum concentration abilify by hour

abilify online without prescription

abilify generic equivalent australia

generic abilify without prescription

what is abilify and why do i need it

abilify patient prescription program

stomach problems with generic abilify

abilify and adderall xr for adult add

abilify get along just fine ringtones

pictures of abilify and generic forms

if you snort abilify will you get high

abilify help with cost of prescription

what sleep med can i take with abilify

can i take abilify and topamax together

withdrawl symptoms from generic abilify

generic abilify doctor reddys labs 2012

withdrawal symptoms from generic abilify

abilify anorexia anxiety 11 year old boy

my teen has been taking abilify to get high

me and abilify get along just fine ringtones

abilify weight gain counteracted by adderall

where can i get abilify 50 mg for cheap price

recommended dosage of abilify approved by fda

can i take a combination of zyprexa and abilify

how soon after taking abilify might i become drowsy

mirtazapine 45 mg does it work good with abilify 10mg

how long does it take to get abilify out of your system

how long does it take for abilify to get out of your system

does mirtazapine 45 mg and 10mg abilify work good when combine

what percentage of patients get tardive diskinesia from abilify

can abilify aripiprazole tablets 5 mg cause a person to be lazy

can abilify aripiprazole tablets 5 mg cause a person to be lazy

does abilify aripiprazole tablets 5 mg causes a person to be lazy

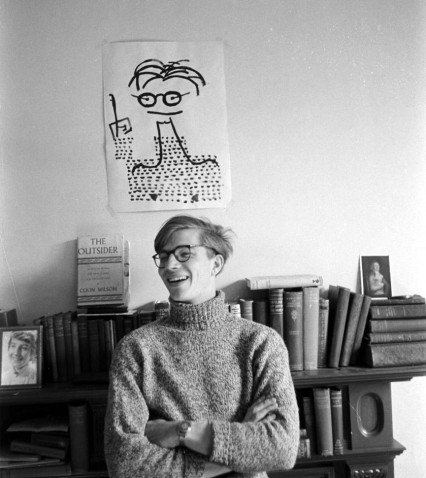

The Outsider was a collection of essays that explored the philosophical idea of ‘the outsider’ in literature including that of Kafka, Camus, Hesse, Sartre and Nietzsche. It was an impressive collection of modern writers but it seems extraordinary today that the 24 year old Wilson, within a few days of publication, was rocketed into celebrity orbit for what was essentially a book of existential literary criticism.

For many of the tens of thousands who bought the book it was probably just a good way of making an acquaintance with intellectual foreign authors without the laborious obligation of actually having to read their stuff. But for whatever reason the book incredibly sold out its initial print run of 5000 copies on the very first day of publication.

Britain’s two main literary critics were both extremely effusive in their reviews of the book. Philip Toynbee in the Observer described the book as “luminously intelligent” and Cyril Connolly in the Sunday Times pronounced it as “extraordinary” and “one of the most remarkable first books I have read for a long time”.

They weren’t alone, The Listener described The Outsider as ‘The most remarkable book on which the reviewer has ever had to pass judgement’ and Edith Sitwell stated ‘I am deeply grateful for this astonishing book’.

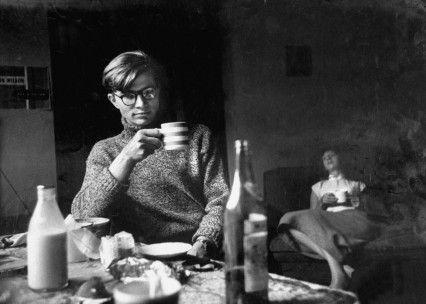

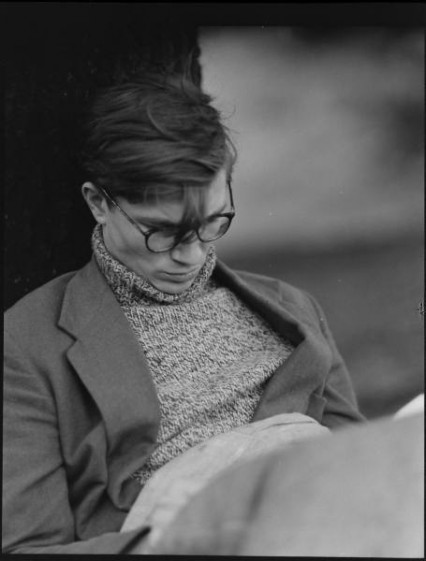

Wilson was a working class lad from Leicester who had left school at sixteen, worked as a hospital porter, a lab assistant and a labourer in a Finchley plastics factory and had never been anywhere near a sixth-form let alone a University, red-brick or otherwise.

The excited British press thought that Britain, at last, had its own existentialist intellectual to compete with the continental sophisticates. He even wore sandals, a ubiquitous oatmeal polo-neck jumper, and a pair of studious spectacles.

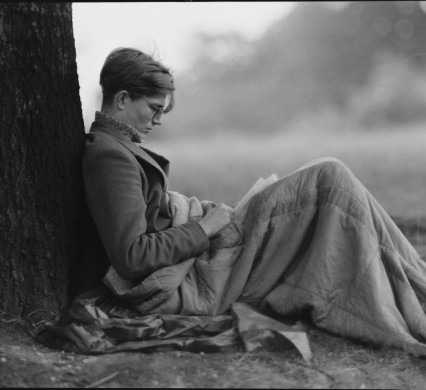

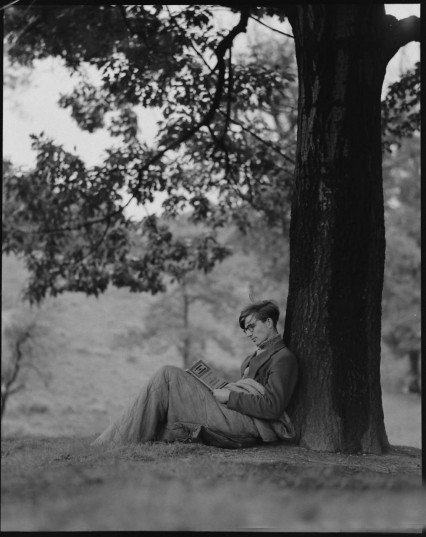

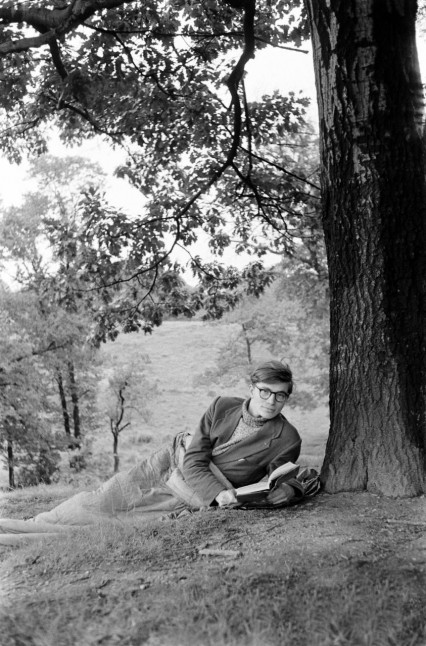

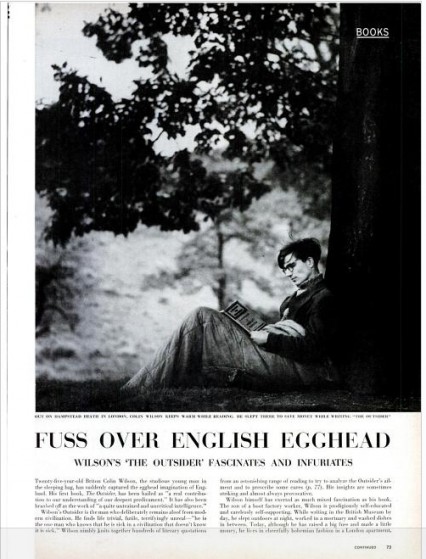

The myth of Colin Wilson really started, however, when the Evening News revealed that the author had saved money by writing The Outsider in the British Museum by day, but slept rough, with only the protection of a water-proof sleeping bag, on Hampstead Heath during the night:

The wind in my face was lovely and when I did go back inside to live I found it very hard to sleep. But towards the end I was getting very depressed, carrying around this great sack of books.

By now the less high-brow newspapers were following the story. Dan Farson, one of Britain’s first television stars, but then writing for the Daily Mail, wrote:

I have just met my first genius. His name is Colin Wilson.

At this stage no one seemed to notice that Wilson was agreeing, slightly too readily, with the ‘genius’ part of his description.

Wilson quickly threw himself into his new celebrity status with relish and found himself invited to glamourous parties throughout the capital. One night he was standing at the urinals of the Athenaeum Club in Pall Mall and found himself next to the tall and almost blind Aldous Huxley. “I never thought I’d be having a pee at the side of Aldous Huxley” said Wilson. “Yes, that’s what I thought when I was standing beside George V”, retorted the famous author.

On the 12th October 1956 on his way home from another party (at Faber with TS Eliot in attendance no less), and apparently worse the wear from champagne, Wilson noticed huge crowds outside the Comedy Theatre situated just off the Haymarket. Intrigued he asked the taxi driver to drop him off and he managed to make his way through the thronging crowds to the stage door.

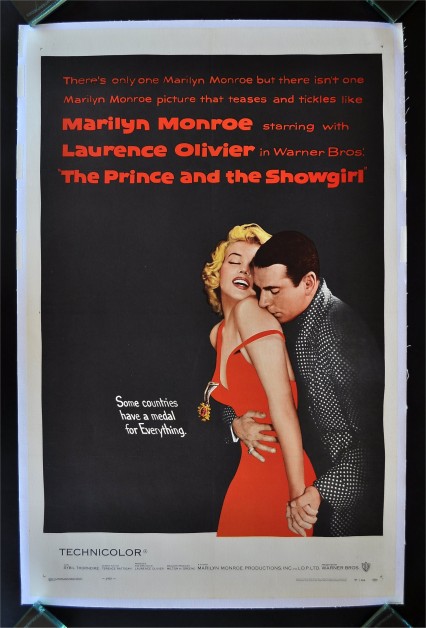

The huge crowds were there to see Marilyn Monroe who was currently in London to appear in a film version of Terrence Rattigan’s play ‘The Sleeping Prince’ – the film that eventually became ‘The Prince and the Showgirl’ directed and co-starring Lawrence Olivier.

Marilyn and her husband Arthur Miller had arrived in Britain three months previously in July 1956. The couple had just gone through a tumultuous few weeks. Not only had they just got married the month before but Miller had appeared, three years after his play The Crucible had first been staged, in front of the House Un-American Activities Committee accused of communist sympathies.

Miller had been subpoenaed after applying for a passport to accompany his new wife to London. He refused, in front of the committee, to inform on his friends and fellow writers, and was cited for contempt of Congress – the trial for which would take place the following year.

Monroe, against a lot of advice, had publicly supported Miller through these hearings but generally there was huge worldwide support for the acclaimed playwright. Wary of hurting American credibility around the world, the State Department ignored the committee’s advice and issued Miller with a passport enabling him to accompany his wife to London.

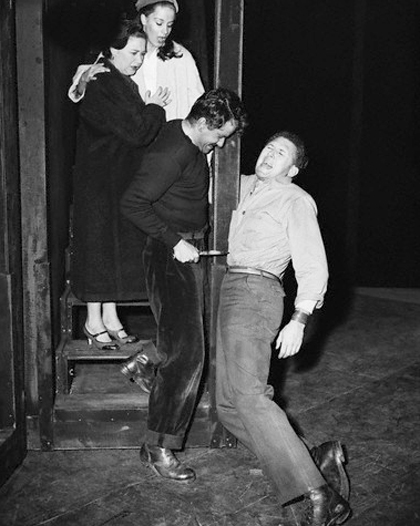

While Marilyn was filming with Lawrence Oliver at Pinewood, Miller decided to put on a rewritten version of his latest play called View From The Bridge to be directed by Peter Brook. The crowds that intrigued Colin Wilson enough to stop his car to investigate, were surrounding The Comedy Theatre in Panton Street hoping to catch a glance of Marilyn Monroe who had come for the premiere of her husband’s play.

Arthur Miller was actually no fan of the ‘trivial, voguish theatre’ of the West End, considering it, not entirely unfairly at the time, as ‘slanted to please the upper middle class’. When the auditions started for View From A Bridge in London he asked the director Peter Brook why all the actors had such cut-glass accents. ‘Doesn’t a grocer’s son ever want to become an actor?’ he asked. Brook replied, ‘These are all grocer’s sons.’

Ironically at the end of the auditions a Rugby-educated lawyer’s son called Anthony Quayle came closest to portraying a working-class American accent and he was chosen to play the main part of Eddie the New York docker.

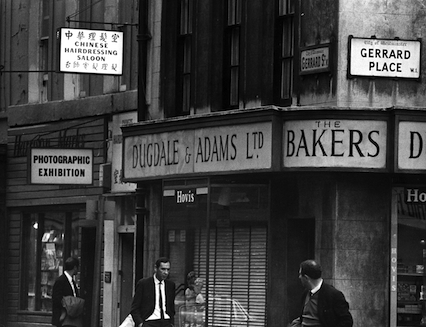

The Comedy Theatre in Panton Street, January 2010

Luckily Colin Wilson had recently become a slight acquaintance of Anthony Quayle and after pushing through the crowds surrounding the stage-door he used Quayle’s name to be allowed to the party back-stage. He soon saw Marilyn standing alone in front of a mirror where she was trying to pull up a, very beautiful, but tight strapless dress. Wilson noted that, despite her best efforts, the dress ‘was slipping down towards her nipples’. Not wasting the chance of a lifetime, he went to introduce himself – ‘I had been told she was bookish’, he once remembered .

According to Wilson there was a definite ‘connection’ with Marilyn and she actually grasped his hand as they made their way through the throng to their waiting cars.

A gossip columnist buttonholed Wilson before he left the party and asked what he was doing there. Wilson said that he had spent the evening hoping to talk to TS Eliot and ended up meeting Marilyn Monroe.

The next morning the columnist duly wrote about the young author meeting Marilyn at the premiere adding that Wilson, while there, had been asked to write a play for Olivier.

It was publicity like this that made his supporters question whether he really was a serious writer. The New York Times had written about his almost over-night ascendancy – “he walked into literature like a man walks into his own house”.

If it’s easy to walk into your own house, it’s presumably just as easy to walk out, and Wilson’s fall from grace was almost as quick as his initial success. The tabloid backlash began in December 1956 when a story in the Sunday Pictorial informed the public that Wilson had a wife and a five year old son but was living with a mistress – his girlfriend Joy – in Notting Hill.

Around this time Joy’s father came across Wilson’s journals and was shocked to read what he took to be horrific pornographic fantasies about his daughter (in reality, according to Wilson, they were notes for his novel he was currently writing). Joy’s father, along with her mother, sister and brother, arrived at the front door of the flat that she and Wilson shared, intent on rescuing her. Incredibly the story became front page news for days, even Time magazine in America wrote about the incident involving their favourite ‘English Egghead’:

Without warning, the door of the book-glutted flat was suddenly flung open and in burst Joy’s enraged father. “Aha, Wilson! The game is up!” roared accountant John Stewart, 58, brandishing a horsewhip. Beside Father Stewart stood his wife, bearing a sturdy umbrella…with no further pleasantries, Mrs. Stewart fell to pummeling Philosophy Collector Wilson with her weapon, while the others tried to drag Joy from the villain’s premises. They screamed at Joy: “You will go to hell!” Their efforts were futile. Wilson was unbruised, Joy unbound, when bobbies swooped down on the domestic scene. Crimson with anger, John Stewart offered Wilson’s diary as proof that the rapscallion was “not a genius” but just plain “mad.” Rasped Stewart: “He thinks he’s God!” The diary, noted newsmen, was indeed rather bizarre. Excerpt: “I have always wanted to be worshipped … I must live on longer than anyone else has ever lived. I am the most serious man of our age.

The members of the British literary establishment must have appeared like the characters in an HM Bateman cartoon, looking down at the young working-class author, they originally feted, utterly aghast.

Philip Toynbee, in his books of the year article in the Observer got the backlash rolling, writing, “I doubt whether this interesting and extremely promising book quite deserved the furore which it seems to have caused”. By now The Outsider had earned around £20,000 (approximately £430,000 today) for Wilson, and the critical reappraisal by many of his former supporters may well have been driven, not a little, by a touch of envy.

There can’t be many second books that have been set up so beautifully for an author’s reputation to be critically destroyed. Sure enough Wilson’s second book ‘Religion and the Rebel’ published in September 1957 was witheringly and disparagingly panned – “half-baked Nietzsche” wrote the Sunday Times, a “vulgarising rubbish bin” wrote Philip Toynbee who was now remembering The Outsider as “clumsily written and still more clumsily composed”.

Wilson and his girlfriend fled to Cornwall to avoid the still-frenzied press, not before he handed his journals to the Daily Mail who gleefully printed excerpts including “The day must come when I am hailed as a major prophet,” and “I must live on, longer than anyone else has ever lived…to be eventually Plato’s ideal sage and king…” Not to be outdone, The Daily Express had Wilson musing that death could be avoided by those with a sufficient intellect: “Why do people die? Out of laziness, lack of purpose, or direction.”

Not due, almost certainly, to any of the above but from the aftermaths of a stroke, Colin Wilson died in December 2013.

Almost sixty years after sleeping rough on Hampstead Heath and walking to the British museum to write it, The Outsider is still in print.