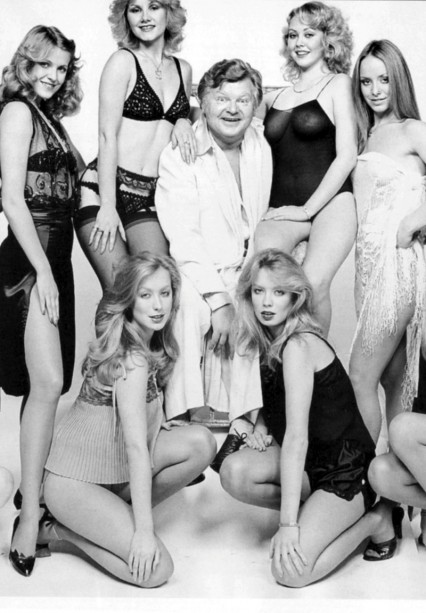

Benny Hill in his sixties heyday.

“The notion that Benny was a lonely man is so depressing and wrong. He just liked his own company. He was very happy walking alone, living alone, eating alone, taking holidays alone and going to see shows alone. I often wonder whether he needed anybody else in his life at all…except perhaps a cameraman”. – Bob Monkhouse

On Easter Sunday morning in 1992, and just two hours after he had been speaking to a television producer about yet another come-back, 75 year-old Frankie Howerd collapsed and died of heart failure.

Benny Hill, seven years younger than Howerd, was quoted in the press as being “very upset” and saying, “We were great, great friends”. Indeed they had been friends, but Hill hadn’t given a quote about his fellow comedian, he hadn’t even been asked for one – he couldn’t have been – because he was already dead.

The quote about Howerd had come from Hill’s friend, former producer and unofficial press-agent Dennis Kirkland who had not been able to get in contact with Hill for a couple of days and was starting to worry.

It wasn’t until the 20th, the day after Howerd had died, that a neighbour noticed an unpleasant smell coming from Flat 7 of Fairwater House on the Twickenham Road in Teddington.

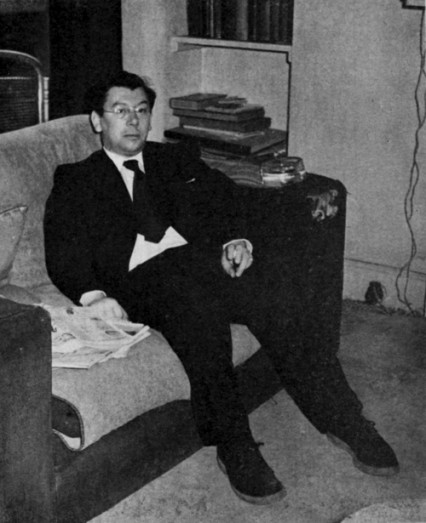

Benny Hill at home in 1991. Exactly where he was found a year later slumped on the sofa watching TV

Fairwater House on the Twickenham Road in Teddington

The neighbour contacted Kirkland, who was a regular visitor to the Teddington apartment block, and it wasn’t long before the television producer was climbing a ladder and peering through the window of Hill’s second floor flat. Inside he saw his friend surrounded by dirty plates, glasses, video-tapes and piles of papers slumped on the sofa in front of the TV. He was blue, the body had bloated and distended, and blood had seeped from the ears. Hill had been dead for two days.

Frankie Howerd and Benny Hill had both been part of a big wave of ex-servicemen comedians that came to prominence after the second world war. This amazing generation of performers, in some form or other, would eventually almost take over light-entertainment, initially on the radio and subsequently television, in the fifties, sixties and seventies.

Benny Hill, although he was still known by his original name Alfie Hill, had first come to London during the war. He arrived at Waterloo station on the Southampton train in the summer of 1941 having given up his milk-round and sold his drum kit for £8 to fund this next stage of his life. He had no other plan in his head but to succeed as a comic performer on the London stage and had three addresses of variety theatres in his pocket. He was just seventeen.

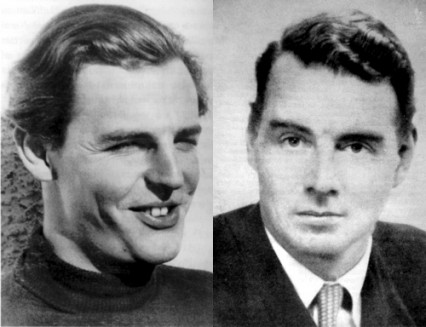

Young Benny Hill

More by luck than judgement and after a week or two of sleeping rough in a Streatham bomb shelter, the naive Hampshire boy managed to get a dogsbody job from a kindly agent. Hill remembered this in 1955:

At the Chiswick Empire they did not want to know about Alf Hill. I had much the same reception at the “Met”, but at the Chelsea Palace I was lucky enough to arrange to see Harry Benet at his office the next morning.

Harry Benet offered Hill £3 per week to be an Assistant Stage Manager (with small parts) for a new revue called Follow the Fan. Years later Hill would often joke that although he was no longer an ASM he still had small parts.

12 months or so later Hill, now eighteen, had become eligible for conscription. He was having the time of his life and he naively thought that by travelling around the country (he was now with Send Them Victorious, another revue) he could pretend he had never received the OHMS manila envelope ordering him to enlist.

The ruse worked until November 1942 when the revue was at the New Theatre in Cardiff for the last engagement before the pantomime season. Two military policeman presented themselves at the theatre stage door and Hill was ‘advised’ to ‘give himself up’. Within a month Hill found himself a private in the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers as a driver/mechanic.

He couldn’t drive and knew nothing about engines and Alfie Hill played no useful part in the war. After VE day, and when he was in London on leave, he applied to be part of the services’ touring revue called Stars in Battledress.

Benny Hill in the army

There was one problem, Hill didn’t have ‘an act’ and he had 24 hours to create one. For inspiration he walked to the Windmill Theatre in Soho as it was the only place in London where you could see comedians during the day.

He noticed one Windmill comic in particular, a man called Peter Waring whose scripts were written by Frank Muir, at that time still attached to the RAF. Hill would later say:

Waring was the biggest influence on my life. He was delicate, highly strung and sensitive…when I saw him I thought, ‘My God, it’s so easy. You don’t have to come on shouting, “Ere, ‘ere, missus! Got the music ‘Arry? Now missus, don’t get your knickers in a twist!” You can come on like Waring and say, “Not many in tonight. There’s enough room at the back to play rugby. My God, they are playing rugby.

The Windmill Theatre on Great Windmill Street in 1940

Archer Street, which is on one side of the Windmill Theatre, in the late-forties. Musicians and performers looking for work would meet up with small-time agents here.

Windmill Theatre

The Windmill Theatre on the corner of Great Windmill street and Archer Street, just off Shaftesbury Avenue, was a magnet to many of the new wave ex-servicemen comedians, of which there were many. The theatre was infamous for its risque dancing girls and nude tableaux but it was a tough crowd for comedians who would make up part of the show. Not too many patrons were there for the jokes.

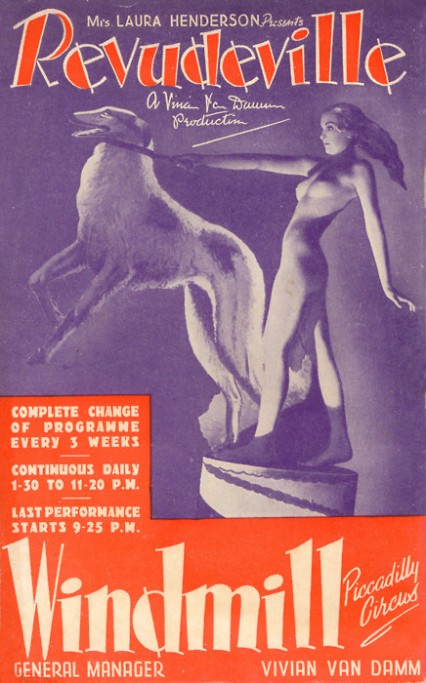

The theatre had been bought in 1930 by a 70 year old ‘white haired, bright eyed little woman in mink’ called Mrs Laura Henderson whose late husband “had been something in Jute”. At the time it was a run-down old cinema called the Palais de Luxe (actually one of the first in London) but she had the building extensively rebuilt, glamourously faced with glazed white terracotta and renamed it the Windmill Theatre.

Under the careful guidance of her manager Vivian Van Damme, a small neat man who more often than not would be smoking a cigar, the theatre slowly became a success. The ‘Mill’, as it became known in its heyday, started to present a non-stop type of revue that was a winning combination of brand-new comedians, a small resident ballet, a singer or two and, of course the infamous static nude tableaux. The terrible title of the show assimilated the word ‘nude’ and ‘revue’ and was called Revudeville.

Revudeville cover

The elderly Vivian Van Damm showing Benny Hill how its done.

Van Damme, amusingly known as V.D. to everyone backstage, had an astute judgement of both English sexual taste and of what the Lord Chamberlain – the national theatre censor – would allow. “It’s all right to be nude, but if it moves, it’s rude,” said Rowland Thomas Baring, 2nd Earl of Cromer who was the Lord Chamberlain at the time.

On the Sunday night before a new show opened Van Damme would invite the Earl of Cromer to a special performance. To make the Lord Chamberlain’s mood amenable to what he was about to see V.D. made sure there was generous hospitality before the curtain was raised. It was said that the Lord Chamberlain never delegated his responsibilities on these occasions.

During the war the Windmill Theatre became one of the first theatres to re-open after the Government initially ordered compulsory closure of all the theatres in the West End (4-16 September 1939). It stayed open throughout the rest of the war with five or six performances a day and open from 11am to 10.35 at night.

Windmill Girls

Windmill Girls

Windmill Girls

Once the audience arrived in the morning some of them would stay and watch all the six shows throughout the evening and night. Des O’Connor, just one of the comedians who got an early break at the Windmill, was on his fifth show of the day when he completely dried up. Somebody, who had been at all the previous shows that day, shouted out: “You do the one about the parrot next!”

During the latter performances the audience that were sitting in the back of the stalls would wait for those in the front rows to get up and leave. When they did the men at the back would quickly leap over the seats to get to the front. This was known as the ‘Windmill Steeplechase’.

During the worst of the Blitz it was sometimes too dangerous to expect people to get home and the stagehands and performers often sheltered in the lower two floors underground. Around 1943 the theatre created its famous motto – “We never closed” – although this quickly became “we never Clothed”.

Life magazine featured the Windmill Theatre and its girls during the war.

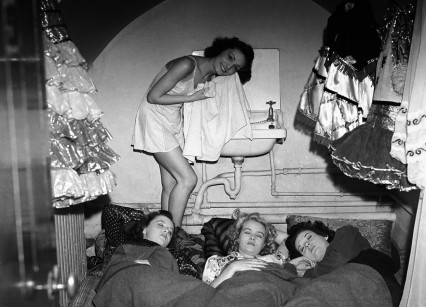

Windmill Girls sleeping in the basement of the theatre during the Blitz

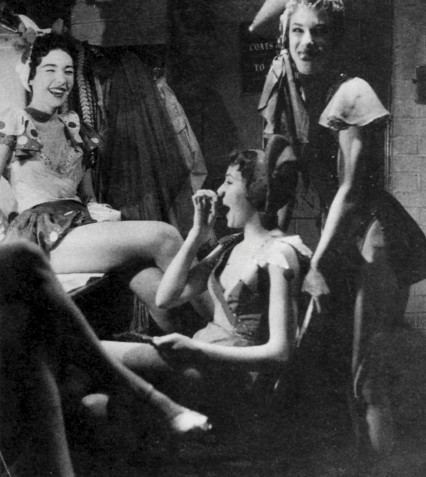

Windmill girls in the dressing room

In fact the ‘Mill’ became internationally famous for staying open for business despite the constant threat of the German bombers. Extraordinarily, this reputation of defiance, together with Van Damme’s tasteful’ girl-next-door version of English femininity, made the Windmill theatre a major symbol for London’s ‘Blitz Spirit’ all around the world.

This indestructible gesture of defiance was summed up at the theatre when one naked young woman broke the ‘no moving’ rule by brazenly raising her hand to thumb her nose at a V1 bomb that had exploded nearby. She earned herself a standing ovation.

Piccadilly Circus, about a hundred yards from the Windmill, in the black-out during the Blitz

Benny Hill, who by now had changed his name (Jack Benny was one of his favourite comedians), had two auditions at the Windmill. On both occasions, and after barely finishing his first gag, Hill got a dreaded ‘Thank you, next please’ from Van Damm somewhere in the darkness of the stalls.

He wasn’t the only comedian who would later go on to become a huge star but be rejected by the Windmill theatre. Both Bob Monkhouse and Norman Wisdom also failed to get past the one-man Van Damm judging panel.

The list of comics that did perform at the Windmill, however, is extraordinary, and included Jimmy Edwards, Tony Hancock, Arthur English, Harry Secombe, Peter Sellers, Michael Bentine, Bruce Forsyth, Dave Allen, Alfred Marks, Max Bygrave, Tommy Cooper and Barry Cryer.

There was a comedy revolution taking place. Performers, who in a sense had wasted years of their young adulthood to the war, were desperate to make up for lost time and they had a connection with each other like no generation since.

For Hill, after failing his second audition at the Windmill, it was back to the working men’s clubs in places like Dagenham, Streatham, Tottenham, Harlesden and Stoke Newington. In those days the Soho agents never actually mentioned money and used to show the amount that was to be paid by laying fingers on the lapels of their jackets. One finger, one pound, two fingers meant two pounds – but it was nearly always the former for Benny in those days.

However his act was getting more and more polished and in 1948, in some rehearsal rooms across the road from the Windmill Theatre on Great Windmill Street, he had an audition as Reg Varney’s straight-man in a revue called Gaytime.

There were two people auditioning for the part but after Hill had performed an English calypso (this would have been pretty rare just after the war) which he sang to his own guitar accompaniment:

‘We have two Bev’ns in our Caninet/Aneurin’s the one with the gift of the gab in it/The other Bev’n's the taciturnist/He knows the importance of being Ernest!’

After his act, Hill was told by Hedley Claxton, an impresario who specialised in seaside shows, that he had got the job. The other contender for the role that afternoon in 1948 was a young impressionist from Camden called Peter Sellers. In 1955, Hill astutely told Picturegoer: “Watch Peter Sellers. He’s going to be the biggest funny man in Britain.”

Hill and Reg Varney’s double act was a success and they were signed up for three seasons of Gaytime and subsequently a touring version of a London Palladium revue called Sky High.

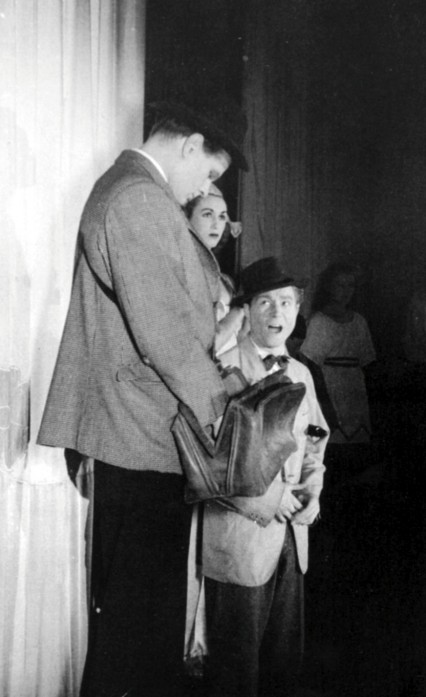

Gaytime with Reg Varney and Benny Hill. Twenty years later Varney would be the first person to use the first ever cashpoint machine in Enfield.

Around this time Hill appeared on BBC radio a few times but struggled to make his mark. A damning BBC report on Benny Hill, dated 10 October 1947 says:

Ronald Waldman: The only trouble with him was that he didn’t make me laugh at all – and for a comedian that’s not very good. It’s a mixture of lack of comedy personality and lack of comedy material.

Harry Pepper: I find him without personality and very dully unfunny.

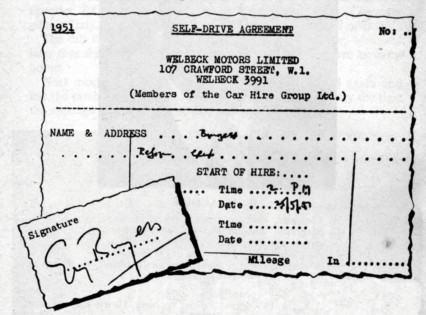

In the early fifties, unlike many performers and agents who either feared it or thought it would be a flash-in-the-pan, Benny realised that television would be massive. He knew, however, that it gobbled up material and could end the career of Variety artists who had successfully performed the same material all their lives. So Hill started to write hundreds and hundreds of sketches and eventually submitted them in person to the same Ronald Waldman who had said just three years before written ‘he didn’t make me laugh at all’.

This time Waldman, now BBC’s head of light entertainment, was actually very impressed and offered Benny Hill his own show right there and then.

‘Hi There’ went out on the 20th August 1951 at 8.15pm. The 45 minute one-off show featured a series of sketches wholly written by Benny Hill and was relatively well-received. It wouldn’t be until four years later that Hill had his own series and in January 1955 the first ever ‘The Benny Hill Show’ was broadcast on the BBC. Hill was always an uncomfortable performer on stage and the new medium of television utterly suited his “conspiratorial glances and anticipatory smirks” to camera and after a shaky first episode the rest of the series was a huge success.

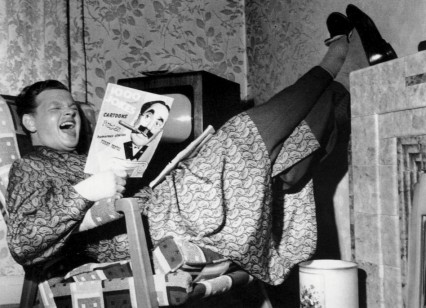

Benny enjoying his new found success. He had paid his dues though.

Benny with his dancing girls on the first ever Benny Hill Show on the BBC

Plus ça change...still surrounded by his dancing girls over thirty years later.

Benny Hill never looked back and was a mainstay of British television for the next thirty five years. Initially his shows appeared on the BBC and then subsequently on Thames Television from 1969 when the new London weekday franchise needed some high-profile signings.

The ‘cherub sent by the devil’, as Michael Caine once described Hill, eventually became a huge star all over the world. It seemed at one point, just as many in the UK were starting to find his comedy rather old-fashioned and sexist, that the rest of the world thought Benny Hill was British comedy.

Twenty years after Hill made his first series for Thames Television their new Head of Light Entertainment John Howard Davies invited him into the offices for a chat. Benny assumed that they were meeting to discuss details of a new series – he’d just gone down a storm in Cannes.

Davies thanked him for all his series he had made for Thames and then promptly sacked him. Hill never really recovered from the shock and considering what he had done for the company over the last two decades he was treated badly. It was only three years later that he was found dead in his apartment a stone’s throw from the Thames Television studios in Teddington.

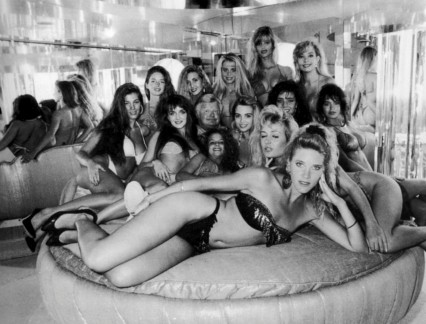

Benny and yet more women. Again.

There is no doubt that Benny Hill had a strange relationship with women. He was very confused about the accusations of sexism in the latter part of his career. He felt that his comedy hadn’t really changed and he’d been doing almost the same thing for decades. This was true, he literally had been telling the same jokes for decades always happy to recycle his own material, but society around him had moved on and an elderly man surrounded or chased by very scantily-clad women made for uncomfortable viewing.

It appears that hill never really had a proper relationship during his lifetime. The closest he got to marriage was with a dancer from the Windmill Theatre called Doris Deal around the mid-fifties. He took her for meals in London, they held hands, and it was assumed they were seeing each other, but when Hill had procrastinated a little too long and told her he wasn’t ready for marriage she promptly left him.

There were other close albeit non-romantic relationships with women through the years including a young Australian actress called Annette André whowould eventually star in Randall and Hopkirk (Deceased). He may have even proposed to her but if he did she said she pretended not to notice.

It seems that Benny Hill, famous throughout the world by surrounding himself with young women, either was scared of intimate sexual intercourse or, as some un-named sources have implied, that he was impotent. It was probably a combination of the two.

Benny Hill out with friends in 1955, his girlfriend Doris Deal is front left

Benny Hill and Bob Monkhouse. Two people who failed their Windmill Theatre audition.

He wanted his women to be more naive than he was, women who would look up to him. He also said it was fellatio he wanted, or masturbation. “But Bob, I get a thrill when they’re kneeling there, between my knees and they’re looking up at me. And I want them to call me Mr Hill, not Benny. ‘Is that all right for you , Mr Hill?’ That’s lovely, that is, I really like that,” I asked him why and he said, “well, it’s respectful.”

Benny Hill and an uncomfortable-looking Jane Leeves (of Frasier fame) once a Hill's Angel.

Clips from BBC Benny Hill shows from the sixties.

An interview with Benny Hill from early in his career.

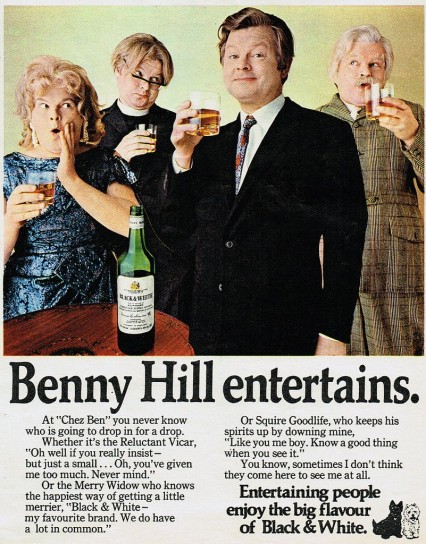

Benny Hill Entertains

Hmm.

Windmill Theatre today. Is it not possible to get rid of the black cladding?

The Whitehall theatre is now a lap-dancing club. The sign outside says ‘Probably the most exciting men’s club in the world…’ I haven’t been there, but I’m sure it’s safe to say, it almost certainly isn’t.

When I was a lad and crazy to get into showbiz I used to dream of being a comic in a touring revue. They were extraordinary, wonderful shows. There were jugglers and acrobats and singers and comics, and most important of all were the girl dancers. My shows are probably the nearest thing there is on TV to those old revues. – Benny Hill, 1991

Buy Benny Hill’s Ultimate Collection here (only £2.49!)