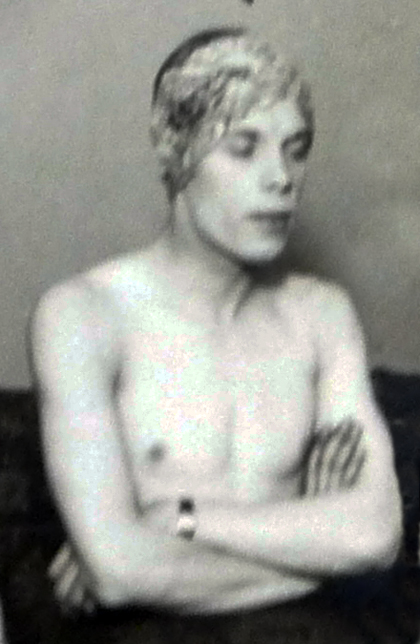

Police photograph of Bobby Britt and his party guests at his flat at 25 Fitzroy Square, January 1927

At one in the morning on the 16th January 1927 Superintendent George Collins of the Metropolitan police knocked on the door of the basement flat at 25 Fitzroy Square. A woman called Constance Carre answered and was told that there was a warrant to arrest the occupants. Carre responded:

But Mr Britt was going to give us a Salome dance!

The Superintendent and his fellow officers barged past here and quickly entered the flat. They came across a 26 year old man who was wearing, as a police report would later describe, ‘a thin black transparent skirt, with gilt trimming round the edge and a red sash… tied round his loins.’ The report added ‘he wore ladys (sic) shoes and was naked from the loins upwards.’

The oddly attired man gave his name as Robert Britt and said:

I am employed in the chorus of ‘Lady Be Good’. These are a few friends of mine. I was going to give an exhibition dance when you came in.

I have been here for about eight months and pay two pounds five shillings weekly for the flat. Carre is my housekeeper. I was a Valet to a gentleman for about nine years who died last November. I did not like that sort of life, so as I’m considered good at fancy dancing I decided to go on stage… Some of the men I have known for a long time and they bring along any of their friends if they care to do so.

It eventually came to light that the police had been staking out Britt’s flat for a month or so. Sergeant Spencer and Police Constable Gavin of “D” division had spent 16th, 17th December 1926 and 1st and 2nd of January 1927 essentially peering into the abode from the front and rear of the property. They noted the activities during various parties Robert Britt held at his flat.

Police Sergeant Arthur Spencer wrote:

At 11.45pm I saw two men, who I saw enter at 11.30pm leave, they were undoubtedly men of the “Nancy type”. They walked cuddling one another to Tottenham Court Road, where they stood waiting for a bus. I stood close to them and saw their faces were powdered and painted and their appearance and manner strongly suggested them to be importuners of men.

Police Constable Gavin contributed to the report:

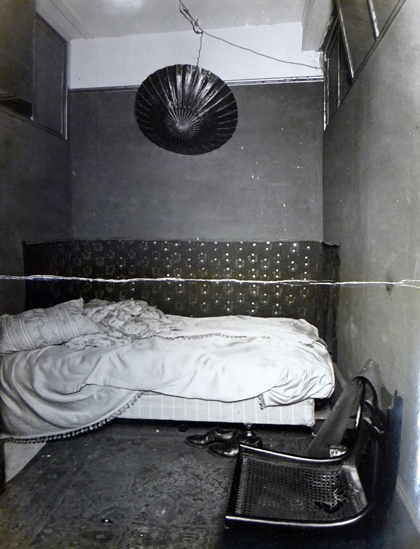

I saw from the a roof into a bedroom in the basement, where two men enter the bedroom, they both undressed and got into bed and the light was put out. I heard them laugh and scream in very effeminate voices.

The bedroom in Bobby Britt’s Flat as photographed by the police at the raid.

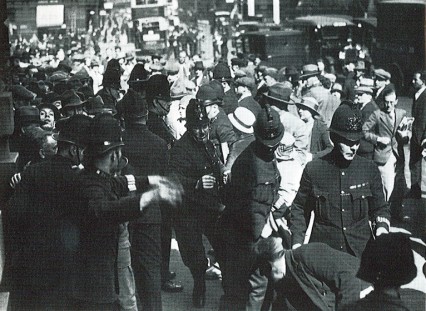

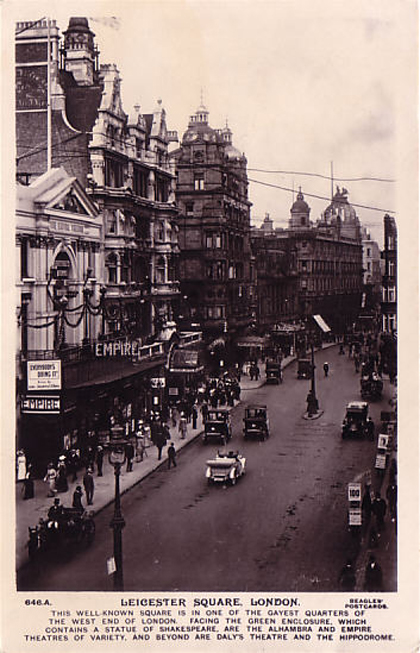

Fitzroy Square in the 1920s

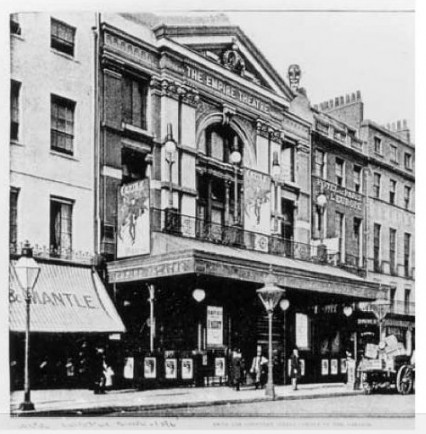

Londoner Bobby Britt, the youngest of four children, had been born in Camberwell at the turn of the century and was now 26 years old. As he mentioned to the police when they raided his flat he was performing at the Empire Theatre in the dancing chorus of Lady Be Good! – the Gershwin brothers’ first Broadway musical and which starred the brother and sister team of Fred and Adele Astaire. The musical had been a huge success in New York and had now transferred to the famous theatre in Leicester Square to perhaps even greater acclaim. Bobby Britt was dancing in easily the hottest show in town.

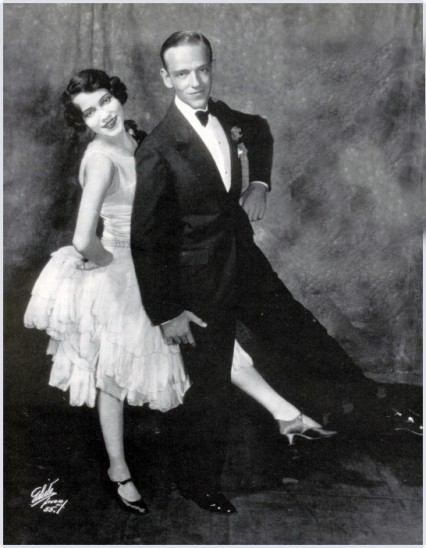

Fred and Adele Astaire in Lady Be Good

Leicester Square “is one of the gayest quarters of London”. Almost certainly the word ‘gay’ would have already been in use by a few people to mean homosexual around this time. Albeit not by postcard writers.

George Gershwin attended the opening night in London which brought huge crowds to the theatre. Later with the Astaires he partied at the fashionable Embassy Club, where apparently he stayed until eight in the morning.

The Embassy Club, the location for the first night party of Lady Be Good!

Lady Be Good established the Astaires as international celebrities and the Times enthusiastically wrote:

Columbus may have danced with joy at discovering America, but how he would have cavorted had he also discovered Fred and Adele Astaire!

Adele and her younger brother Fred had been a successful vaudeville act since 1905 and in 1926 Adele was actually the bigger star of the two – Fred at this stage of his career played almost a supporting role. Professionally the siblings were completely different; Fred, a constant worrier, was never happy with his or his sister’s performance and usually arrived at the theatre two hours early to limber up and practice, while Adele, a much more relaxed individual, would generally turn up a few minutes before her first entrance.

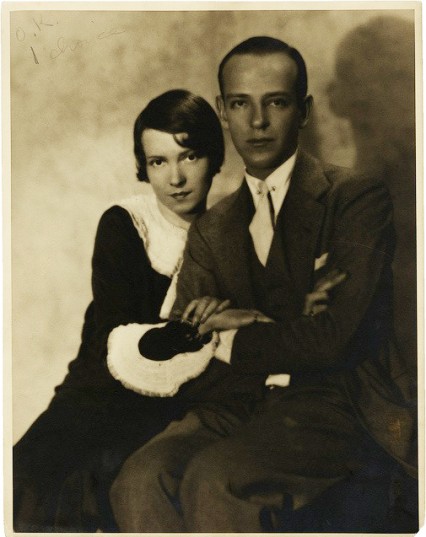

Fred and Adele – vaudeville dancers in 1915

Fred and Adele

Adele enjoyed her new found celebrity status on both sides of the Atlantic and particularly appreciated the attention she had started to get from rich tycoons’ sons and wealthy young aristocrats. In 1932 she retired from the stage and her professional relationship with her brother when she married Lord Charles Arthur Francis Cavendish and moved to Ireland, where they lived at Lismore Castle.

Although she had been dancing most of her life, Adele made no attempt to hide the fact that the theatrical life wasn’t really for her – “It was an acquired taste,” she said, “like olives.”

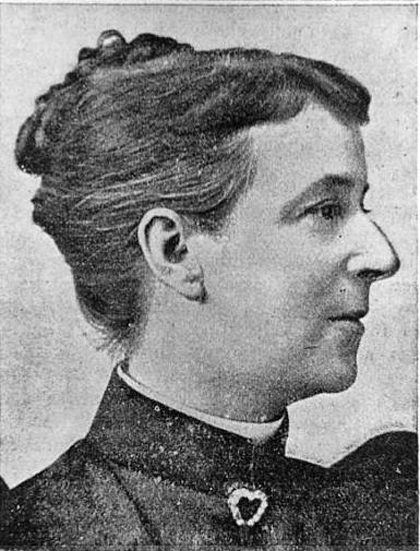

The future Lady Charles Cavendish

The Empire Theatre around the turn of the century

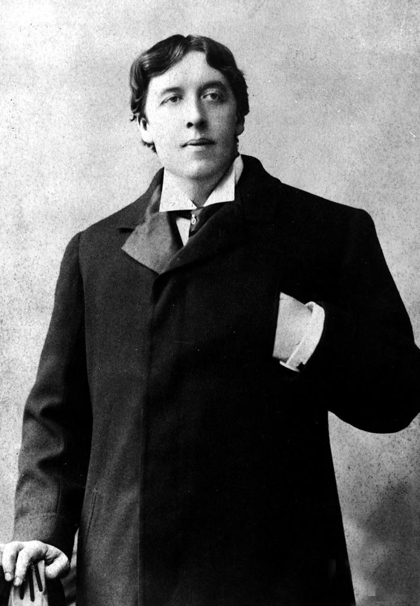

Thirty years before Fred and Adele danced on the stage of the Empire to such acclaim, Oscar Wilde had his character Algernon Moncrieff mention the theatre in the first act of The importance of Being Ernest’.

Algernon. What shall we do after dinner? Go to a theatre?

Jack. Oh no! I loathe listening.

Algernon. Well, let us go to the Club?

Jack. Oh, no! I hate talking

Algernon. Well, we might trot round to the Empire at ten?

Jack. Oh, no! I can’t bear looking at things. It is so silly.

The original production of Oscar Wilde’s play ‘The Importance of Being Earnest’ showing Irene Vanbrugh as Gwendolen Fairfax and and George Alexander as John Worthing. 1895.

Oscar Wilde, who wrote his last and ultimately most successful play during August 1896, would have known exactly what connotations a lot of the audience would glean from ‘the Empire’ reference.

While Wilde had been writing the play the Empire had been in the news for months, mostly because of the ‘purity campaign’ by the indomitable campaigner against vice – Mrs Ormiston Chant. The Daily Telegraph gave it huge coverage worried about ‘the prudes on the prowl’.

The Indomitable Mrs Ormiston Chant

Prostitution and the theatre, of course, had always been pretty close bedfellows, so to speak. At Wilton’s music hall, for instance, it was flagrant, the gallery could only be entered through the brothel inside which the hall had been built.

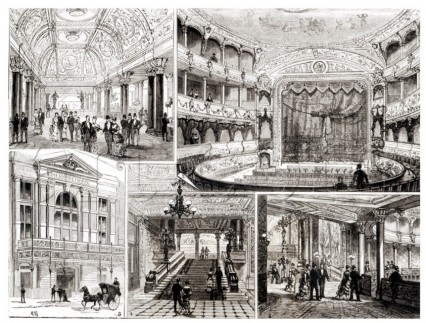

In the 1890s the Empire in Leicester Square was justly famous as a Variety and Musical Hall theatre especially for its spectacular ballet productions and its ‘Living Pictures’ – frozen-moment representations of well-known paintings or other familiar scenes where seemingly half-naked young men and women stood very very still.

In reality, the dominant attraction, and to what Wilde was probably referring, was the Empire’s second-tier promenade. This was an area behind the dress circle, where you could still see the stage if you wanted to, but was essentially a pick up joint for high class prostitutes. The theatre charged half a crown (12 1/2p) for a rover ticket that gave you licence to enjoy the promenade. There was room to wander around but there were also comfortable seats and what was called an ‘American Bar’ serving one shilling cocktails such as the ‘Bosom Caresser’ and the ‘Corpse Reviver’.

The luxurious and opulent interior of the Empire Theatre. The tier two promenade is on the bottom right.

The promenade was known as ‘The Cosmopolitan Club of the World’ and the essayist and caricaturist Max Beerhohm described it as “the reputed hub of all the wild gaiety in London – that Nirvana where gilded youth and painter beauty meet…in a glare of electric light.”

Enchanted Mrs Chant was not, and she was of the opinion that it was the risque ‘abbreviated costumes’ on stage that contributed to, and encouraged the indecent and indecorous air of the Promenade. She told the London County Council responsible for the licensing of the Empire:

“We have no right to sanction on the stage that which if it were done in the street would compel a policeman to lock the offender up…The whole question would be solved if men, and not women, were at stake. Men would refuse to exhibit their bodies nightly in this way.”

Her efforts were not in vain and she managed to persuade the council in October 1894 to instruct the Empire to build a barrier between the theatre itself and the infamous ‘haunt of vice’ promenade.

When the Empire Theatre management put up canvas screens to hide the auditorium from the Promenade they were quickly torn down by a rioting audience. They were egged on by the young Sandhurst cadet Winston Churchill who wrote to his brother:

Did you see the papers about the riot at the Empire last Saturday? It was I who led the rioters – and made a speech to the crowd – “Ladies of the Empire, I stand for Liberty!”.

The Empire Theatre in 1896

Presumably Mrs Ormiston Chant would have been even more shocked and horrified if she had known what was going on within the less prestigious and cheaper first tier promenade. Oscar Wilde, however, almost certainly did, and his ‘Empire’ reference would have had other connotation altogether to a more select part of his play’s audience.

At a cheaper price of only one shilling the Empire Theatre’s first tier promenade was said to be THE gay pick-up location in the whole of London. A letter to the council dated 15 October 1894, just six weeks after Mrs Chant’s visit to the theatre, described the rough ejection of a man from the shilling promenade by Robert Ahern, the front of house manager. The letter writer described the man who was thrown out “as a ‘sodomite’ as were perhaps half the occupants of that promenade, that it was the only venue for people of this kind, and that he ‘could lay his hands on 200 sods every night in the week if he liked.”

Oscar Wilde in 1895

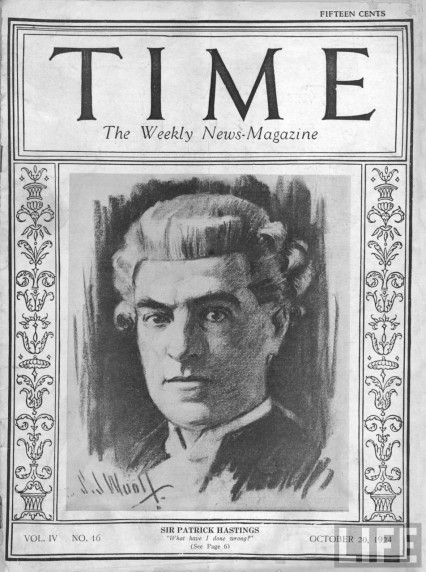

It’s not known whether Oscar Wilde ever went to ‘look at things’ in the first tier promenade at the Empire Theatre but it does sound like the place he would have frequented around that time. However just a few months after Mrs Ormiston Chant’s intervention at the Empire, and only two months after The Importance of Being Ernest premiered at the St James Theatre in February 1895, Wilde was charged with gross indecency after a failed libel case with the belligerent little Marquess of Queensbury. Wilde was convicted under Section 11 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885, and sentenced to two years’ hard labour.

The judge, Mr Justice Wills described the sentence, the maximum allowed at the time, as “totally inadequate for a case such as this,”. Wilde’s response was “And I? May I say nothing, my Lord?” but it was drowned out in cries of “Shame in the courtroom. Five years later he was dead. A broken man.

The last photograph of Oscar Wilde in 1900

Bobby Britt, 1927 naked above his loins.

Thirty years later Lady Be Good! finished its run at the Empire on 22nd January 1927. Bobby Britt was no longer in the chorus because exactly two weeks previously he had been formally charged with keeping a disorderly house. Or to put it in slightly more detail he was charged with permitting:

…divers immoral lewd, and evil disposed persons, tippling whoring, using obscene language, indecently exposing their private naked parts, and behaving in a lewd, obscene and disorderly and riotous manner to the manifest corruption of the morals of His Majesty’s Liege Subjects, the evil example of others in the like case, offending and against the Peace of Our Lord the King, his Crown and Dignity.

After some legal arguing about what a disorderly house actually meant, poor Bobby Britt was sentenced to 15 months hard labour for essentially being a ‘nancy boy’ and enjoying the occasional party. Four of his friends were sentenced to six months without hard labour.

When Bobby was eventually released in 1928 let’s hope that he was able to go and enjoy Oscar Wilde’s Salome, perhaps to compare dances. The play, forty years after it was written (it was banned by the Lord Chamberlain on the basis that it was illegal to depict Biblical characters on stage), had its first public performance at the Savoy theatre in 1931.

After his time in prison Bobby took the stage-name Robert Linden and lived with his parents on Lansdowne Road in Stockwell and then after the war with his sister in Amhurst Road in Hackney. Bobby went on to dance in many shows both in the West End and on Broadway in New York, working with Cecil Beaton, Frederick Ashton and Noel Coward. He danced at the initial BBC television trials at Alexander Palace and he performed for the Royal family at Windsor Castle.

Britt eventually moved to West Sussex and became a proficient painter in his eighties and he died at the age of 100 in the year 2000.

An influence for Mr Britt? Maude Allan as Salome and the head of John the Baptist in 1906.

Maud Allan became known as the ‘Salome Dancer’. Interesting character – her brother was hanged for murder of two women, she published an illustrated sex manual for women in 1900 and in 1918 it was implied by the British MP Noel Pemberton Billing in his article ‘The Cult of the Clitoris’, that she was a lesbian associate of German wartime conspirators. She sewed her own costumes though.

The silent film star and dancer Alla Nazimova stars as Salome in 1923.

After Lady Be Good’s run had come to an end Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Pictures, who had recently bought the Empire, promptly demolished the famous old theatre and built a large cinema in its place. The Empire Theatre cinema, in one form or another, still exists to this day.

The Empire Theatre just after the war, it was showing the film Bad Bascomb with Wallace Beery and Margaret O’Brien.

The Empire Cinema today. It seems a long long way from Fred and Adele Astaire. More respect for the original building please.

25 Fitzroy Square today.

To try and recreate the ‘Naughty Nineties’ atmosphere at the Empire Theatre you may want to try the cocktails Bosom Caresser and Corpse Reviver.

Bosom Caresser

1 tea-spoon raspberry syrup

1 egg

1 jigger brandy

milk

Fill a mixing-glass one-third full of fine ice; add a teaspoonful raspberry syrup, one fresh egg, one jigger brandy; fill with milk, shake well, and strain.

Stir well with ice and strain in to a cocktail glass.

By the way Harry Craddock, who wrote a famous cocktail book in 1930 and worked at the Savoy Hotel wrote that the Corpse Reviver No. 1 should be drunk “before 11am, or whenever steam and energy are needed.”

Cleo Laine and Johnny Dankworth – Oh Lady Be Good!

The Berry Brothers and Eleanor Powell perform Fascinatin’ Rhythm from Lady Be Good 1946