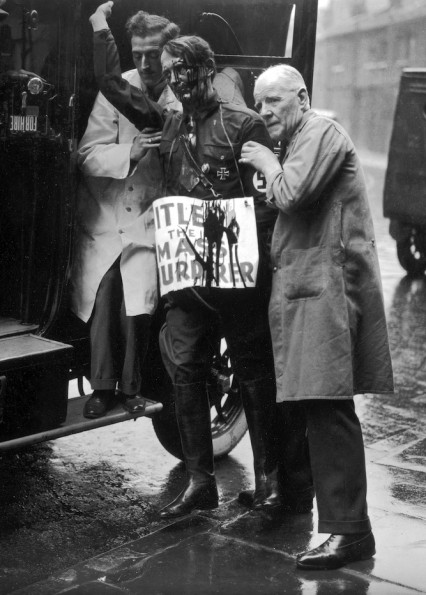

The Madame Tussaud’s wax work of Hitler being taken to Marylebone Magistrates’ court as evidence used towards the conviction of three men and a woman. 1933.

At Madame Tussauds on the Marylebone Road a pot of red paint was poured over a wax effigy of a man who had just been made Chancellor of Germany three months previously. A hand-drawn notice was hung around the neck and it read: “Hitler, the Mass Murderer”. Three men and a woman, not overly hasty in trying to escape, were soon arrested and remanded in custody.

The next day, on 14 April 1933, at the Marylebone Magistrates court, Mrs Bradley who was one of the protestors, was charged with assaulting and obstructing the police. She told the court that the paint-throwing was intended as a protest against “Herr Rosenberg’s representation of a murderous Government”. She was eventually discharged but not before supporters in the court had started shouting in unison, “down with Hitler, down with Hitler”.

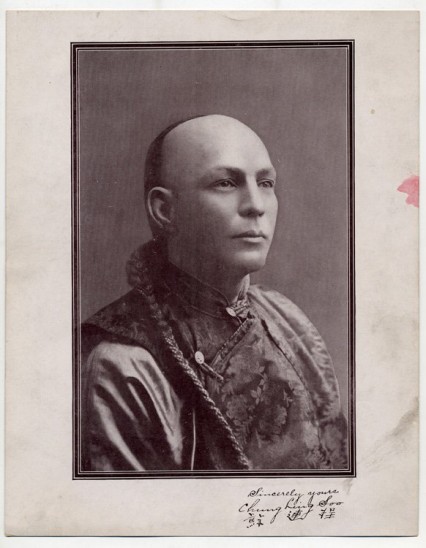

“Herr Rosenberg” or Dr Alfred Rosenberg, to give him his full name, was editor-in-chief of the Nazi daily newspaper Volkischer Beobachter. He had inspired the paint-throwers’ wrath by laying a wreath at the base of the Whitehall Cenotaph after which he had stepped back, raised his right arm and given a Nazi salute.

Rosenberg was described by Reuters at the time as ‘one of the Nazi “Big Five,”’ and acting on Hitler’s behest, and as his unofficial Foreign Secretary, he was visiting the capital ostensibly to discuss the deadlock of the Disarmament Conference. In reality the visit was more about gauging British opinion of the new German National Socialist regime.

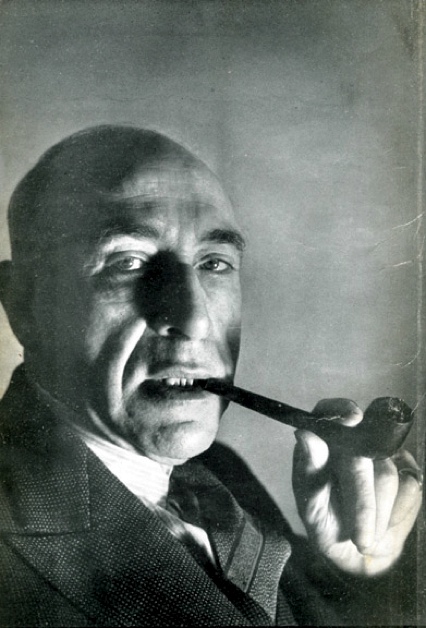

Alfred Rosenberg and Hitler

Rosenberg’s wreath was made of lilies and laurel leaves and was draped with a band in the German imperial colours and which included a black swastika but it wasn’t in position long before it was grabbed that evening by James Sears – a war veteran and a prospective Parliamentary candidate for southwest St Pancras. Sears promptly ran the two hundred yards down Derby Gate and threw it into the Thames. The river police did manage to retrieve what was left of the wreath but it was thought to be too damaged to be of any worth and it was, seemingly without much thought, rather casually thrown away. Sears was later charged with theft but fined only a paltry two pounds.

The next morning the Daily Telegraph reported that a female singer at Covent Garden burst into laughter on hearing of the fate of the Nazi wreath. The singer wasn’t named by the paper but it was probably Lotte Lehmann who had a Jewish husband and was appearing in Sir Thomas Beecham’s Rosenkavalier at the time. Her reaction, however, infuriated some of her more Nazi-sympathising German colleagues.

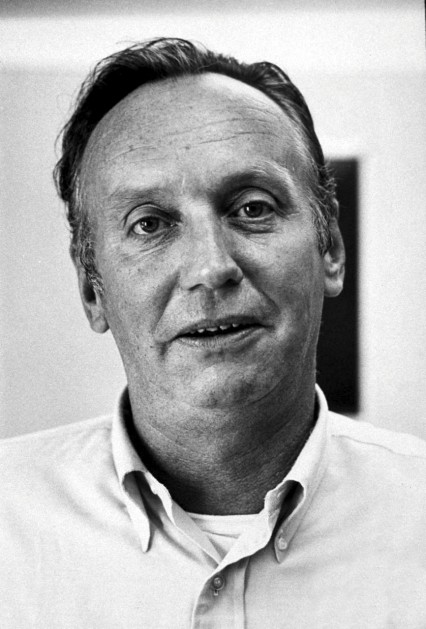

In Berlin the British Ambassador Sir Horace Rumbold, an astute and perceptive critic of the National Socialists, was brought before an incensed Hitler. Why, asked the German Chancellor, had the English court imposed such a pathetic and lenient sentence on the desecrator of his wreath? The ambassador, one presumes rather bravely, informed him that there had been an unmistakeable change in British public opinion about Germany based on concepts of freedom and consideration for other races. Not entirely surprisingly Sir Horace was asked to resign a few weeks later.

Sir Horace Rumbold

.

Dr Alfred Rosenberg wasn’t the only person to give a fascist salute at the Cenotaph. On the 10th September 1934: A party of 280 Italian tourists who laid a wreath on the Cenotaph, Whitehall, London gave the Fascist salute after doing so. The Italian Football team would do the same a month later.

20th January 1936: Bearing a swastika flag, German ex-servicemen marching to the Cenotaph in London to lay a wreath. They were guests of British ex-servicemen. George V died the same day.

The Cenotaph had originally been built in 1919 for the first anniversary of the Armistice and was intended just as a temporary monument and initially been built of wood and plaster. It was such a success with the public, who piled wreath after wreath of flowers around the monument that the architect, Sir Edwin Lutyens was asked to rebuild it in Portland stone for the following year.

All religious imagery was avoided and it was simply inscribed with the words “The Glorious Dead”. It was once calculated that if the British dead from World War One had marched by the Cenotaph four abreast it would have taken them three and a half days to march by.

Footage of the funeral of the unknown warrior at Westminster Abbey.

July 1919. The temporary Cenotaph being erected in Whitehall

Sir Edwin Lutyen’s temporary Cenotaph in 1919

Three quarters of a million British soldiers were killed during WW1 with one and a half million men seriously injured. Almost a third of all the boys and young men aged between 14 and 24 at the beginning of the war would end up being killed. It is entirely unsurprising that after the war there was an almost tangible sense of a ‘lost generation’ hanging over the country.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, whose son Kingsley had been injured at the battle of Somme and like so many of his contemporaries had died in 1918 of pneumonia, wrote in 1926: “The deaths occurring in almost every family in the land brought a sudden and concentrated interest in the life after death. People not only asked the question, ‘If a man dies shall he live again?’ but they eagerly sought to know if communication was possible with the dear ones they had lost. They sought for ‘the touch of a vanished hand, and the sound of a voice that is still’.

In 1922 on 11 November a sixty year old woman called Ada Emma Deane, with the help of her nineteen year old daughter Violet, set up a camera on top of a wall near the corner of Richmond Terrace with Whitehall. From this position she took two photographs of the large crowd around the cenotaph. The first picture was taken just before the annual silence commemorating the Armistice while the second photograph was taken with a long exposure during the entire two minutes. When the photographs were developed one showed a mass of light over some of the audience while the other purported to show a ‘river of faces’ and an ‘aerial procession of men’ floating over the bowed heads of the crowd.

The Armistice ceremony by Ada Deane

The Cenotaph Armistice ceremony in 1922 by Ada Emma Deane

The images were commercially printed together and distributed amongst spiritualists and other believers of spirit photography of which there were many so soon after the war. Spirit photography had been around for almost as long as photography itself. The long exposures in the early days of photography often produced accidental ghostly images as people came in and out of shot. But so soon after the First World War it was as popular as ever before.

Ada Emma Deane lived at 151 Balls Pond Road in Islington and was already fifty-eight years old in 1920 when she bought an old worn-out quarter-plate camera for nine pence. Her husband had left her a few years previously and she had brought up three children on her own by working as a servant and charwoman.

When the children had grown she took up other interests including breeding pedigree dogs, but also spiritualism. After visiting a local seance in Islington a medium had predicted that Deane would become a psychic photographer and, lo and behold, in June 1920 she produced her first ‘psychic’ picture. Her reputation soon spread amongst the spiritualist community and she became one of Britain’s busiest photographic mediums.

Ada Deane in 1922 with ‘ghostly’ image.

However a final plate was taken by Fred Barlow on his own half plate camera using his own photographic plate of his wife, Ada’s daughter Violet, Ada and Fred himself. He arranged the group, took the picture and developed the plate and upon seeing the negative image he saw Ada Deane’s drapped spirit guide “Bessie” appear above her whilst above her daughter Violet Deane her spirit guide “Stella” also appeared.

According to the Society of Psychical Research, which had been formed by a group of Cambridge Dons in 1882 to scientifically investigate the miry world of telepathy, hypnotism and the survival of the soul, Deane would eventually hold over 2000 sessions. At about the same time as Ada Deane her rather odd photography career, a forty year old man called Harry Price joined the Society. Incidentally the SPR still exists to this day and has included members such as Carl Jung, WB Yeats, Charles Dodgson and Alistair Sim.

Price had married a relatively wealthy heiress called Constance Mary Knight twelve years previously in 1908 and had decided to use his newfound independent means to become a psychic investigator. He was an amateur but adept conjuror and photographer and used this expertise to quickly become the Society’s leading expert at exposing duplicitous and fraudulent mediums – especially “spirit” photographers.

Harry Price

Harry Price and Constance in 1908

The most famous of these was a former docker called William Hope, described, not without snobbery by the Illustrated London News at the time, as ‘a niggardly, coarse-mouthed man’. Hope had been producing ‘spirit’ photographs since 1905 and would have been Ada Deane’s major influence. In 1922 Hope extraordinarily agreed to be tested by Price under the auspices of the SPR.

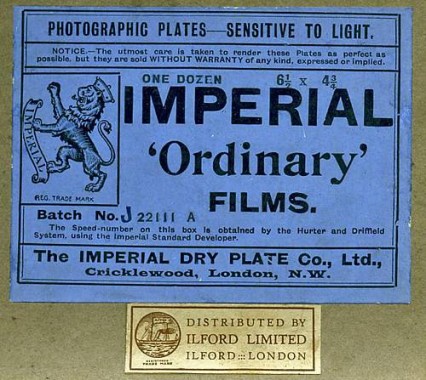

Hope wrote to Harry Price requesting him to bring a half-dozen packet of ¼ inch plates for the experiment – “Imperial or Wellington Wards are considered preferable”. He added, however, that he would have to use his own camera.

Imperial Ordinary Plates

Imperial Plates

Imperial Plates

Price quickly visited the Imperial Dry Plate Co. Ltd in Cricklewood and discussed with them a way of devising an incontrovertible test for Hope. Price wrote to the SPR:

“We have decided as the best method that the plates shall be exposed to the X-Rays, with a leaden figure of lion rampant (the trade mark of the Imperial Co) intervening…Any plate developed will reveal a quarter of design, besides any photograph or ‘extra’ that may be on the plate. This will show us absolutely whether the plates have been substituted.”

On the 24th February 1922 Price, bringing with him his x-rayed Imperial plates, visited William Hope. After a verse of ‘Nearer my God to Thee’ and a long improvised prayer by the photographer, Price was taken to the dark-room. Here Price surreptitiously marked the plate-holder he had been given with a pin-pricking instrument on his thumb. He also noticed that Hope, while away from the safe-light and presumably thinking he couldn’t be seen, had slipped the plate-holder into his breast pocket and then seemingly taken it out again.

When they returned to the studio and Hope had developed the print Price noticed the pinpricks had disappeared and the Imperial logo had failed to appear. Although a strange ghostly female apparition had.

Harry Price with ghostly apparition by William Hope

Later that day Price developed his unused plates and saw the remaining parts of the Imperial logo. He also noticed that the glass of the plate Hope had developed was made of thinner glass although Imperial had confirmed with him that the original plates were all made from the same piece. This was, at last, unassailable proof that Hope was a charlatan and a cheat.

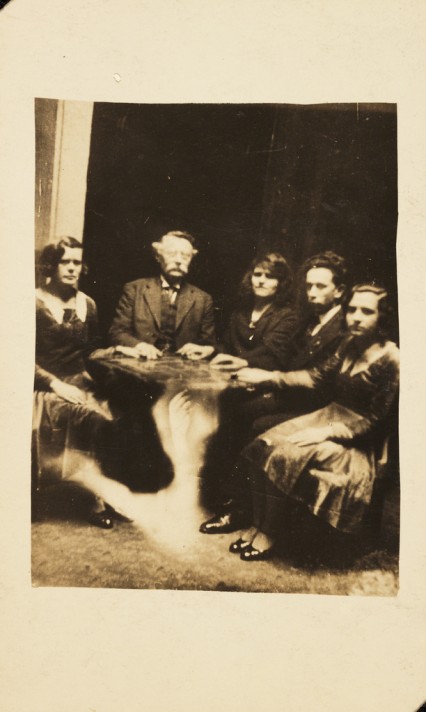

The reverse of the photograph reads: ‘Why is the child always pushing to the front?’ and ‘Do we get messages from the higher spirits?’; perhaps questions the women wanted answering. One of the sitters, at Hope’s request, has signed the plate for authentication.

A photograph of a group gathered at a seance, taken by William Hope (1863-1933) in about 1920. The information accompanying the spirit album states that the table is levitating. In reality, the image of a ghostly arm has been superimposed over the table using a double exposure.

Harry Price published the findings in the SPR’s Journal in May and also printed the exposure in a sixpenny pamphlet called Cold Light on Spiritualistic Phenomena. The result was a worldwide sensation and it made Harry Price a national celebrity.

Ada Emma Deane was not discouraged by the exposé of William Hope and continued with her supernatural photography. Within two years, however, she had a downfall of her own. This time without the help of the now famous psychic investigator Harry Price.

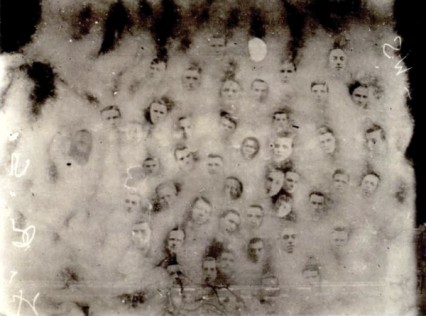

In 1924 Ada Deane again photographed the Cenotaph ceremony during the two minutes of silence. At the request of her spiritual guides she had been ‘storing up power’ by refusing any other sittings for the preceding three weeks.

By now Ada Deane’s annual cenotaph photographs were eagerly awaited and the Daily Sketch had to outbid its rival Daily Graphic for the right to reproduce her latest picture.

Ada Deane’s Armistice picture 1924

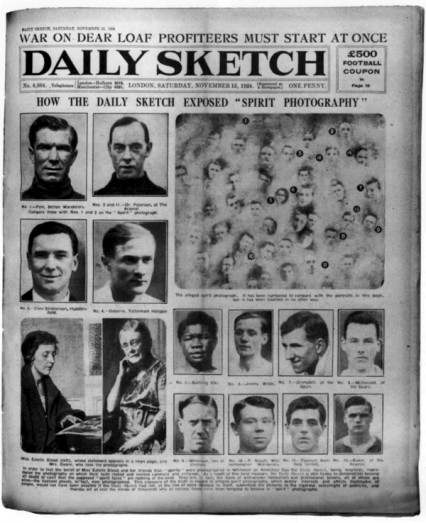

At first the newspaper simply asked of the faces: “Whose are they?”, but two days later the newspaper answered its own question with a front page headline:

HOW THE DAILY SKETCH EXPOSED ‘SPIRIT PHOTOGRAPHY’.

The Daily Sketch

The newspaper had noticed that the faces in the crowd that Deane had ‘photographed’ were not brave fallen soldiers but were actually cut-out pictures of footballers and boxers that were all very much alive. The newspaper wrote:

The exposure of truth in regard to alleged spirit photography, which deeply interests and affects multitudes of people, would not have been possible if the Daily Sketch had not, at the risk of some obloquy to itself, submitted the pictures to the rigorous searchlight of publicity, and thereby set at rest the minds of thousands who at various times have been tempted to believe in ‘spirit’ photography.

The Daily Sketch quickly challenged Deane to produce some ‘spirit’ photographs using the newspaper’s own equipment. They even offered £1000 to charity if she managed to produce them under fair and scientific conditions. Not entirely surprisingly she emphatically refused.

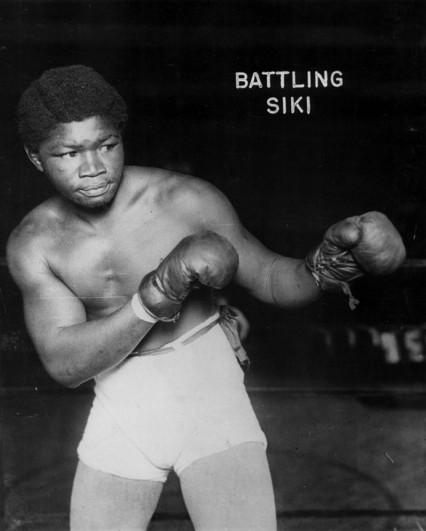

One of the sportsmen in the picture was Sengalese-born ‘Battling’ Siki who was briefly Light Heavyweight champion when he knocked out Georges Carpentier in 1922. He died in 1925 in New York in mysterious circumstances having been shot in the back twice.

After the Daily Sketch’s exposure of her fraudulent activities Ada Deane rarely publicly produced her spirit photographs again. She later wrote:

It was a sorry day for me when I discovered this photographic power. My life has lost all its ease and serenity. Before I was respected and happy in my work, though poor; and today I am poor and look back on twelve years of worry and trouble and am a cock-shy for any newspaper penny-a-liner… I admit that many of the results obtained through me (in a way I have not the least inkling of) have every appearance of having been produced by trickery but I do no more understand how or why than you do.

Ada Deane had a relatively long wait before she had the chance to prove spirit photography once and for all and appear in someone else’s photograph (a chance, as far as we know, she hasn’t taken) and died at the age of 93 in Barnet in 1956.

Harry Price, who always enjoyed his celebrity status a little too much to be of any real importance in proper scientific research on the supernatural, nonetheless set up his own National Laboratory of Psychical Research at 16 Queensberry Place in South Kensington (the building is now occupied by the College of Psychic Studies) in 1925. It’s aim, Price wrote, ‘was to investigate in a dispassionate manner and by purely scientific means every phase of psychic or alleged psychic phenomena.”

College of Psychic Studies today at 16 Queensberry Place, South Kensington.

In 1938 its equipment and library was transferred to the University of London where it still resides. Ten years later, Price died of a massive heart attack while sitting at his desk in his house in Pulborough.

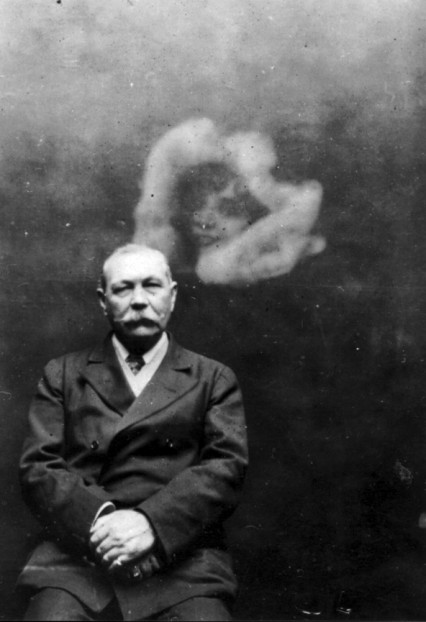

William Hope, even after Harry Price had seemingly proved him nothing but a fraudster, retained some loyal followers including author and spiritualist-believer Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Doyle even wrote a book called ‘The Case for Spirit Photography’ where he went to great lengths to argue the case for Ada Deane and William Hope.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle by Ada Deane

Alfred Rosenberg (his name incidentally is originally Estonian) was captured by Allied troops after the war. He was tried at Nuremberg and found guilty of the not insignificant crime of “conspiracy to commit crimes against peace; planning, initiating and waging wars of aggression; war crimes; and crimes against humanity”. Rosenberg was the only condemned man at Nuremberg, who when asked at the gallows if he had any last statement to make, replied with only one word: “Nein”. His body was cremated and the ashes, much like his wreath sixteen years previously, were deposited in a nearby river.

A dead Dr Alfred Rosenberg following his hanging for war crimes