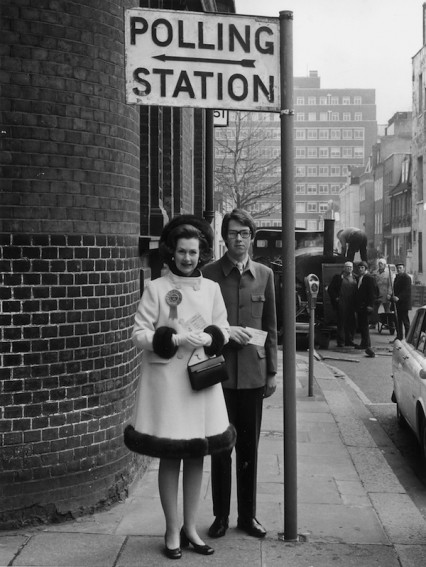

Winifred Atwell. One of Britain’s biggest stars in the 1950s. Modelling Oliver Goldsmith’s sunglasses.

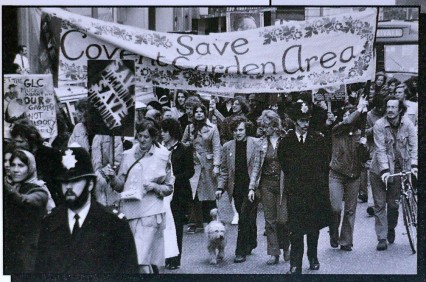

At around eight o’clock on the Saturday evening of 14 April 1981 a Molotov cocktail was thrown through a window of The George Hotel on the corner of Effra Parade and Railton Road in Brixton. It was the second night of the Brixton riots and it was no coincidence that the pub had been targeted – the landlord was infamous in the sixties and seventies for his treatment of local black people and he had been reported to the Race Relations Board for his behaviour.

In the 1970s the pub had been the subject of several local marches and The South London Press, not exactly known to be at the vanguard of radical black separatism, wrote that the arson was “undoubtedly an act of revenge for years of racial discrimination.”

It was relatively un-noticed that the welding shop directly across the road from the George at 82A Railton Road was also set alight. The building all but burnt down during the night and would eventually be demolished.

What was left of 82A Railton Road after the 1981 Brixton Riots.

82A Railton Road around 1975.

Railton Road in 1975. The George pub can be seen in the background on the left behind the greengrocer’s awnings.

The 1981 riots were mainly a reaction to the very heavy-handed Metropolitan Police’s ‘Operation Swamp 81′- it was rather horrendously named after Margaret Thatcher’s 1978 World in Action interview where she said “if there is any fear that it [Britain] might be swamped people are going to react and be rather hostile to those coming in.”. To be fair, and sometimes this isn’t remembered, Thatcher also said in the interview, albeit maybe patronisingly, that “in many ways [minorities] add to the richness and variety of this country”.

It certainly isn’t remembered now, and I doubt it was in 1981, but the building at 82A Railton Road that burnt down that night once housed maybe the first black women’s hairdressers in London. It had opened in 1956 and was called The Winifred Atwell Salon.

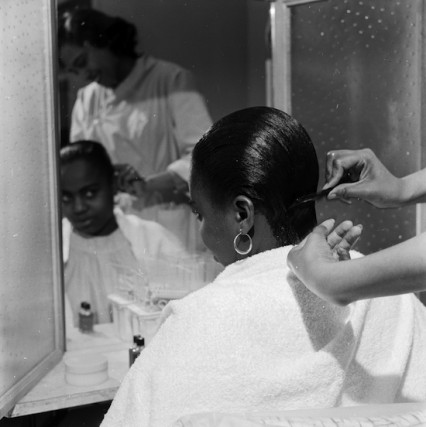

A customer at Winifred Atwell’s hairdressing salon has her hair straightened out. 1957.

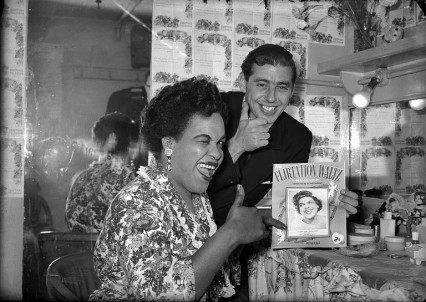

Winifred Atwell’s hairdressing salon, 1957.

Winifred has her hair straightened out at her salon in Brixton, 1957.

In the mid 1950s Winifred Atwell was undoubtedly one of Britain’s most popular entertainers. Trinidadian-born, her undisguised cheerful personality and well-played honky-tonk ragtime music brightened up many a ‘knees up’ in the fifties. In fact when Atwell reached number one in 1954 with ‘Let’s Have Another Party’, she became the first black musician in this country to sell a million records.

Between 1952 when she reached number five with ‘Britannia Rag’ (written for her appearance at the Royal Variety Show that year), and 1959 when Piano Party reached number ten she had eleven top-ten hits and is still the most successful female instrumentalist to ever have had featured in the British pop charts.

WInifred at the piano.

Winifred Atwell by Walter Hanlon in 1952.

Winifred having a cup of tea and a cigarette before performing in 1952.

At the peak of her popularity her hands were insured for £40,000. It was said, and how many of us would like to sign a legal document like this, that there was a clause in the insurance contract stipulating that she must never wash the dishes.

Atwell, was born in Tunapuna, near Port of Spain in Trinidad around 1914 (most sources say that year but according to her marriage certificate it was 1915 and on her grave it says 1910) and had been playing Chopin recitals since the age of six. After the war she went to study music in New York under the pianist Alexander Borovsky, but arrived in London in 1946 to study classical music piano at the Royal Academy of Music. In the evenings she supported herself by playing ragtime and boogie-woogie at clubs and hotels around London. She had learnt the music playing for servicemen during the war in Trinidad.

A year after Atwell arrived in London she married Reginald ‘Lew’ Levisohn, who gave up his stage career as a variety comedian, and become her manager. Encouraged by Lew, and not discouraged by her professor at the Royal Academy, the former child prodigy was skilfully groomed for stardom and by now she was playing her piano in a rollicking honk-tonk upbeat style.

In 1948 Winifred was booked at a Sunday charity concert at the London Casino (originally and now the Prince Edward Theatre in Old Compton Street) in place of the glamorous actress and singer Carole Lynne who was unwell. The impresario Bernard Delfont, who was married to Lynne, had heard from the agent Keith Devon about a “coloured girl, a pianist, who has the makings of a star.” Winifred Atwell, to huge applause, ended up taking several curtain calls and was immediately signed up by Delfont to a long-term contract.

Within four years she was playing for the new Queen Elizabeth at the 1952 Royal Variety Performance. Winifred completed her act with ‘Britannia Rag’ – a piece of music she had written specially for the occasion.It received a rapturous reception, not least from the Queen, and it was to be her first big hit, reaching number five over Christmas and into the New Year.

Atwell brought the two worlds of her classical piano training and her popular ragtime honky-tonk into her performances. She would open her act with a piece of classical music played on a grand piano but after a short while would then change over, to what she and her audiences came to know as her ‘other piano’ – a beaten up and specially de-tuned upright said to have been bought by her husband in a Battersea junk-shop for just 30 shillings.

Her small journey across the stage between the two pianos encapsulated beautifully how she managed to turn her career from a trained European-classical piano player to the more, even though she was Trinidadian, ‘authentic’ black-American rhythmic music for which she was now famous.

Honky Tonk Winnie

The writer and economist C.B. Purdom wrote that London in the fifties was:

dulled by such extensive drabness, monotony, ignorance and wretchedness that one is overcome by distress.

Purdom wouldn’t be the only person to describe post-war Britain in that way and looking at pictures of Winifred Atwell in the fifties it’s easy to see why she became so popular. The successful record producer and lyricist Norman Newell wrote:

Winnie was around at the right time. Immediately after the war there was a feeling of depression and unhappiness, and she made you feel happy. She had this unique way of making every note she played sound a happy note. She was always smiling and joking. When you were with her you felt you were at a party, and that was the reason for the success of her records.

Introduced by Eamon Andrews, Winifred Atwell playing Poor People of Paris, 1956

In March 1956, and now at the height of her fame, she had her second number one called Poor People of Paris. A few months later she was due to make her second appearance at the Royal Variety Performance which traditionally took place on the first Monday of November. Except this time it never happened. Four hours before the curtain rose, and to the shock of the still-rehearsing all-star cast which included Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh but also Sabrina backed by the Nitwits, the show was suddenly cancelled.

The day before on Sunday 4th November, the Observer had written about the Suez Crisis, declaring that the action against Egypt had “endangered the American Alliance and Nato, split the Commonwealth, flouted the United Nations, shocked the overwhelming majority of world opinion and dishonoured the name of Britain”. Later that Sunday afternoon, at a huge rally at Trafalgar Square attended by 10,000 people or more, Aneurin Bevan told the crowd:

If Sir Antony is sincere in what he says – and he may be – then he is too stupid to be Prime Minister.

The next day the Royal Family decided that maybe it would be best to cancel the show. Bernard Delfont wrote in his autobiography that after the cast were informed: “Winifred Atwell gave an impromptu party in an attempt to lift our spirits.” Whether the Queen’s spirits needed lifting as well we don’t know but Winifred performed later at a private performance for the Queen and Princess Margaret at Buckingham Palace where she played Roll Out the Barrel and other Royal favourites.

And it didn’t. Bernard Delfont complained that he lost a lot of money.

In 1956, Winifred opened her hairdressing Salon on Railton Road. She had lived initially in the area, although was now living in Hampstead, and still had property in Brixton. A very young Sharon Osbourne, then Sharon Arden, and her father Don “Mr Big” Arden – manager of Gene Vincent, Small Faces, ELO and Black Sabbath, lived in a nearby house rented from Winifred Atwell at the time.

Isabelle Lucas, originally a Canadian actress who performed in many National Theatre productions and remembered as Norman Beaton’s wife in The Fosters and also in two separate roles in Eastenders wrote about Atwell:

In those days there were no black salons for black women in this country. Black women styled their hair in their kitchens. I needed advice on how to straighten and style my hair, but I didn’t know any black women in Britain. I had only heard about Winifred Atwell. So one day I looked her up in the London telephone directory and found her listed! I rang her, and to my great surprise she answered! I explained my predicament, and she invited me to her home in Hampstead. It was as easy as that! I met her lovely parents ,whom she brought to this country from Trinidad, and Winifred gave me some hair straightening irons.

At the height of her career Winifred Atwell was one of Britain’s favourite performers. She had her own series on ATV in 1956 and another series on the BBC the following year. For a black woman of that era this was nothing short of extraordinary but unfortunately nothing remains of this TV history.

Winifred performing with the Ted Heath Orchestra at the BBC, 1957.

Winifred Atwell with David Whitfield, Vera Lynn, Eddie Calvert and Mantovani. 1953.

Winifred Atwell in 1953 with fellow pianist Joe ‘Mr Piano’ Henderson.

By the late fifties, however, tastes in music were rapidly changing and Winifred Atwell had her last top ten hit in 1959. Atwell’s manic style either sounded old-fashioned – the era of Rock ‘n’ Roll was now a few years old and not going away – or to people who still liked her style, Russ Conway had taken up her baton and would have six top ten hits in 1959 and 1960.

Winifred Atwell first toured Australia in 1958 and her popularity was such there that when record sales started to dramatically fall in Britain she spent more and more time there. She started to only return for club bookings and the odd television appearance. By 1961 her hairdressing salon in Railton Road had been sold and the premises became A.C. Skinner and Co. Builders merchants.

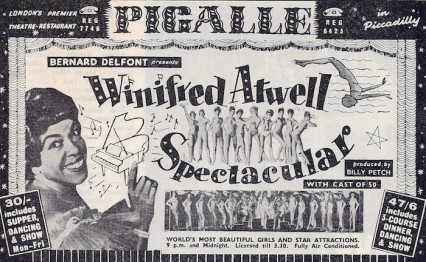

Winifred booked at the Pigalle nightclub in 1961.

In 1971 Atwell was granted permission to stay in Australia and the Daily Mirror reported on the news:

Pianist Winifred Atwell has been given permission to settle down in Australia as an immigrant. She has been told this officially in spite of the country’s ‘White Australia’ policy. An Australian immigration official said yesterday that she had been granted residence because she was ‘of good character and had special qualifications.’ Immigration Minister Mr Phillip Lynch said: ‘We will not stand in the way of an international artist of such repute’.

In 1978 Atwell’s husband Lew died and she never really recovered. In 1981, at around the same time the flaming bottle of petrol was thrown through the window of what used to be her hair salon on the Railton Road, she was finally granted Australian citizenship. She died just two years later from a heart attack in Sydney on 27 February 1983.

The corner of Railton Road and Effra Parade in 2012. The original building, that once housed Winifred Atwell’s Salon and was burnt down in 1981.

The view down Railton Road from the other direction. Showing where the George pub once stood. 2012.

Various versions of Winifred playing Black and White Rag, which became the theme tune for BBC’s snooker series ‘Pot Black’.

Many thanks to Stephen Bourne whose book Black in the British Frame – The Black Experience in British Film and Television’ (Continuum, 2001) helped immensely in writing this post.