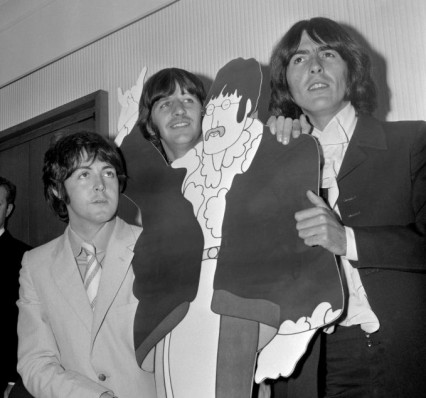

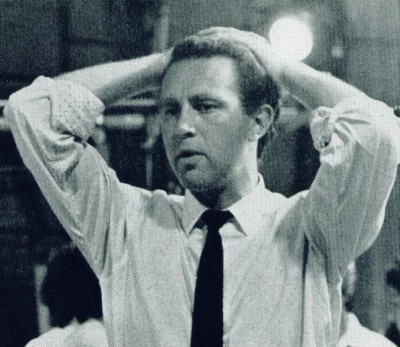

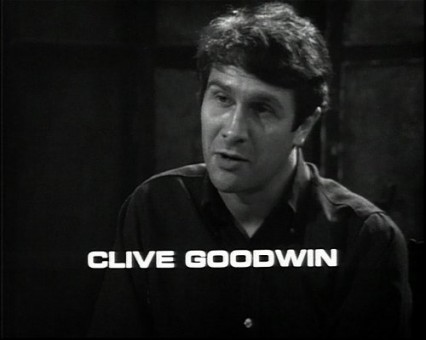

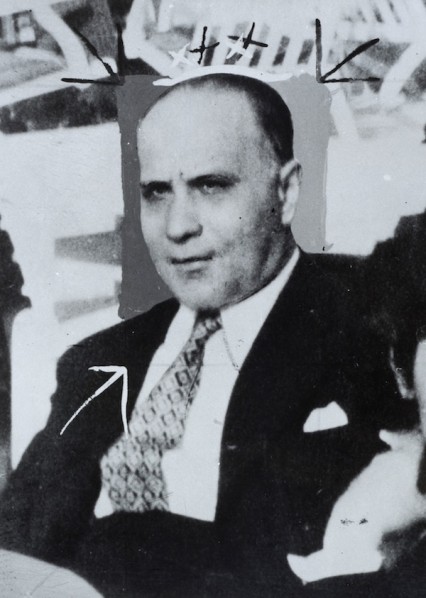

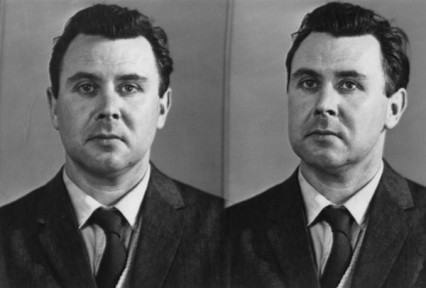

Stan ‘The Spiv’ Setty in 1949.

On March 8 2013 Camden Council permanently closed Warren Street to cars. The road had long been used, presumably for decades, as a rat-run for drivers hoping to avoid the congestion that would often build up at the junction between Tottenham Court Road and the Euston Road.

Closing a road to traffic in central London is hardly unusual these days but in this case there was a certain irony. For much of the 20th century Warren Street had been the centre of the used-car trade in London and was the oldest street car market anywhere in Britain.

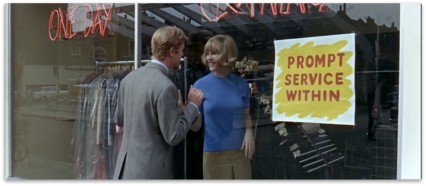

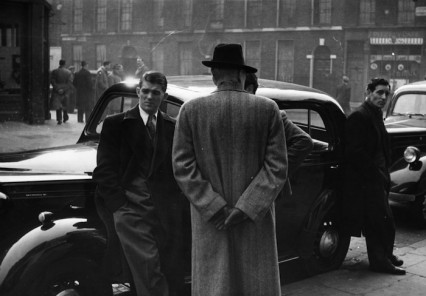

“It’s a nice little runner” – Two car dealers on Warren Street in November 1949.

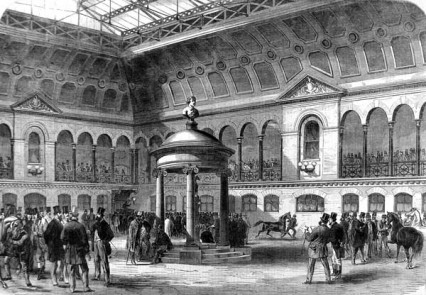

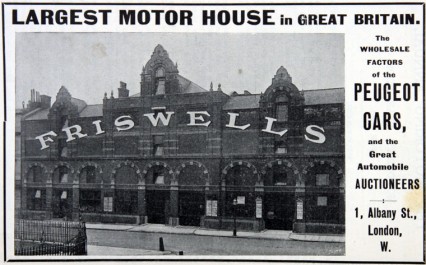

It all started in 1902 when Charles Friswell, an ex-racing cyclist and successful engineer, astutely hopped on the running board of the new burgeoning car industry and opened Friswell’s Automobile Palace at 1 Albany Street on the corner of the Euston Road. It was a five-storey building that could accommodate hundreds of vehicles in garage and showroom spaces, with repair and paint shops, accessory sales and auction facilities. It was known as ‘The House of Friswell’ and ‘The Motor-World’s Tattersalls’ and was a huge success.

Friswell’s Great Motor Repository at Albany Street.

Friswell’s in Albany Street by the Euston Road.

Smaller car dealers started to open along the Euston Road but as the traffic got busier it became harder and harder to park cars outside their main showrooms. Many of the premises, however, had entrances or exits that opened up on the parallel Warren Street (the road was actually built in the 18th century as an access road for the newly built properties on Euston Road).

By the start of the First World War most of the car sales were actually now taking place in Warren Street. The main dealerships were soon joined by ‘small-fry’ or ‘pavement dealers’ – men who bought and sold cars of questionable provenance on street corners, cafes, milk-bars and pubs. Frankie Fraser described Warren Street in his book Mad Frank’s London:

They’d have cars in showrooms and parked on the pavement. There could be up to fifty cars and then again some people would just stand on the pavement and pass on the info that there was a car to sell. Warren Street was mostly for mug punters. Chaps wouldn’t buy one. People would come down from as far away as Scotland to buy a car. All polished and shiny with the clock turned back and the insides hanging out. And if you bought a car and it fell to bits who was you going to complain to?

Car dealers on Warren Street in November 1949.

Warren Street March 2013. Photograph by Lucy King.

Dodgy car-dealer spivs outside 54 Warren Street in 1949.

54 Warren Street today. Photograph by Lucy King.

In December 1949 the magazine Picture Post published an article about the used-car market in Warren Street. They described the road as the northern-most boundary of Soho (Fitzrovia is actually a relatively recent construct and only really been used since the fifties) and explained that was the reason why, “ it attracts a fair amount of gutter garbage from the hinterland.” The reporters feigned shock at the numerous cash-deals that were going on;

Bundles of dirty notes were going across without counting…there is nothing illegal about a cash sale unless, of course, the Income Tax authorities can catch them – which they cannot – or thieves fall out and pick each other’s pockets – or unless, of course, someone gets killed.

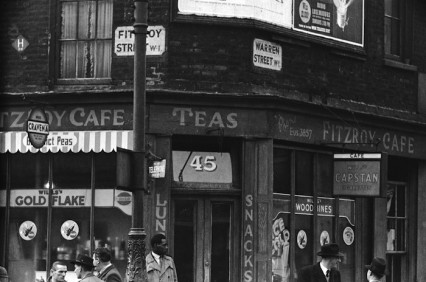

And someone did get killed. His name was Stanley Setty, a shady Warren Street car-dealer, with a lock-up round the corner in Cambridge Terrace Mews . He hadn’t been seen since 4 October when he had sold a Wolseley Twelve saloon to a man in Watford for which he received 200 five pound notes. The next day Setty’s brother-in-law called at Albany Street Police station to report him missing but it also didn’t take long before Setty’s fellow traders and black-marketeers noticed his absence from his usual patch outside the Fitzroy Cafe on the corner of Fitzroy Street and Warren Street.

Car dealers loiter outside the Fitzroy Cafe on the corner of Warren Street and Fitzroy Street in London, 19th November 1949. Stan Setty used the cafe as his personal office.

The former stamping ground of Stanley Setty on the corner of Fitzroy Street and Warren Street today. Photograph by Lucy King.

Stanley Setty’s Citroen parked outside his garage in Cambridge Terrace Mews just north of the Euston Road and west of Albany Street.

Stanley Setty had been born in Baghdad of Jewish parents and arrived in England at the age of four in 1908. Twenty years later he received an eighteen month prison sentence, after pleading guilty to twenty-three offences against the Debtors’ and Bankruptcy Acts. In 1949 he was still an undischarged bankrupt and thus unable to open a bank account. Despite this, or more likely because, Setty dealt in large amounts of cash and he was what was called a ‘kerbside banker’.

It was widely known that, on his person, he never carried anything less than a thousand pounds, and, if he was given a couple of hours notice, he could produce up to five times that amount. His real name was Sulman Seti but to many he was known as ‘Stan the Spiv’.

A spiv in 1945 with a Voigtlander camera for sale on the blackmarket in London. The brooches on his lapels are also for sale.

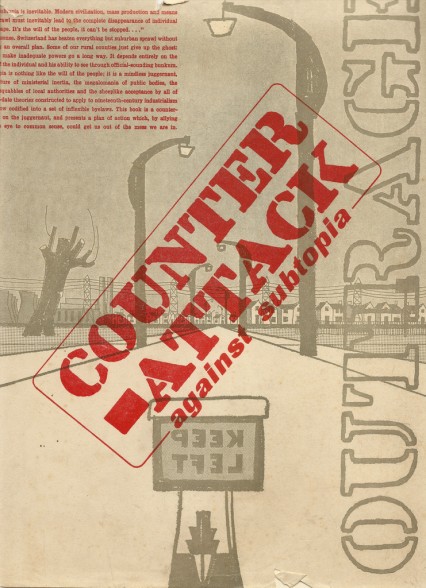

Spiv is a word that’s almost non-existent today and a couple of years ago there were more than a few blank faces when Vince Cable showed his age when describing the City’s much-maligned bankers as ’spivs and gamblers’. After the Second War, however, the word was almost ubiquitous. It was used to describe the smartly-dressed black-marketeers that in a time of controls and restrictions lived by their wits buying and selling ration coupons and sought after luxuries.

When the war had come to an end in the summer of 1945 it was estimated that there were over 20,000 deserters in the country and 10,000 in London alone. These deserters, all without proper identity cards or ration books, had only one choice to make (if they didn’t give themselves up and receive a certain prison sentence) and that was to be part of the huge and growing black market underground.

The word ‘spiv’ had been used by London’s criminal fraternity at least since the nineteenth century and meant a small time crook, con-man or fence rather than a full-time and dangerous villain. The exact origin is lost in the London smog of thieves’ cant, and is etymologically as obscure as the derivation of the goods the spivs were trying to sell. In The Cassell Dictionary of Slang, Jonathon Green suggests the word originally came from the Romany spiv, which meant a sparrow, used by gypsies as a derogatory reference to those who existed by picking up the leavings of their betters, criminal or legitimate.

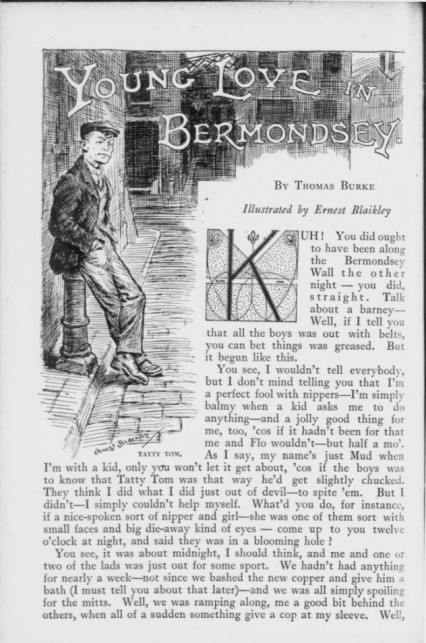

In 1909, the writer Thomas Burke, in a short story featured in the Idler magazine entitled ‘Young Love in Bermondsey’ mentions ‘Spiv’ Bagster, the ‘Westminster Blood’ who can ‘do things when his dander’s up’. Henry’ Spiv’ Bagster actually existed and was a newspaper seller and petty-thief. His many court appearances for selling counterfeit goods and illegal street-trading were occasionally mentioned in the national press between 1903 and 1906.

Thomas Burke wrote about characters from and around Bermondsey including Barney Grierson who was ‘always handy in a scrum’; Hunky Bottles, ‘captain of the Walworth Whangers’, Battlng Bert, Jumbo Flanagan, Greaser Doodles as well as ‘Spiv’ Bagster.

Another theory about the word ‘spiv’ is that it could well have come from the slang term ’spiff’ meaning a well-dressed man. This turned into ’spiffy’ meaning spruced-up and if you were ‘spiffed up’ you were dressed smartly.

Over time the two meanings of ‘spiv’ seemed to have mysteriously combined and in 1945 Bill Naughton, the playwright and author brought up in Bolton but best known for his London play and subsequent film – Alfie, used the word in the title of an article he wrote in September 1945. Written for the News Chronicle, just a few weeks after the end of World War Two, Meet the Spiv began:

Londoners and other city dwellers will recognize him, so will many city magistrates – the slick, flashy, nimble-witted tough, talking sharp slang from the corner of the mouth. He is a sinister by-product of big-city civilisation.

James Agate in the Daily Express reviewing Naughton’s article described the spiv as:

That odd member of society… a London type. Which would be a Chicago gangster if he had the guts.

Housing, food, clothing, fuel, beer, tobacco – all the ordinary comforts of life that we’d taken for granted before the war and naturally expected to become more plentiful again when it ended, became instead more and more scarce and difficult to come by.

By 1946 the archetypal spiv character was more well known, the columnist Warwick Charlton in the Daily Express wrote in November of that year:

The spivs’ shoulders are better upholstered than they have ever been before. Their voices are more knowing, winks more cunning, rolls (of bank-notes) fatter, patent shoes more shiny. The spivs are the “bright boys” who live on their wits. They have only one law: Thou shalt not do an honest day’s work. They have never been known to break this law.

When war came they dodged the call-up; bribed sick men to attend their medicals; bought false identity cards, and, if they were eventually roped in, they deserted. War was their opportunity and they took it and waxed fat, sleek and rich. They organised the black market of war time Britain. Peace had them worried but only for a moment. Shortages are still with us, and the spivs are the peace-time profiteers.

Seventeen days after Stan ‘the Spiv’ Setty went missing, on the 21 October 1949, a farm labourer named Sidney Tiffin was out shooting ducks on the Dengie mud flats about fifteen miles from Southend when he came across a large package wrapped up in carpet felt. He opened it up with his knife to reveal a body still dressed in a silk cream shirt and pale blue silk shorts. The hands were tied behind the back but the head and legs had been hacked roughly away.

It was estimated that the truncated body had been immersed in the sea for over two weeks and without the head it was thought almost impossible to identify. But the celebrated, not least by himself, Superintendent Fred Cherrill of Scotland Yard’s fingerprint department managed to remove the wrinkled skin from Setty’s fingertips which he then stretched over his own fingers to produce some prints. Prints that turned out to be a match for those of Setty’s.

Within a few days the police found more evidence after they had instructed bookmakers around London to look out for the five pound notes they knew Setty had on his person the day he went missing. Five pounds was a lot of money in 1949 (worth over £150 today) and at that time any five pound note withdrawn from a bank would have had its number noted by the clerk along with the name of the withdrawer.

On the 26th October one of the Setty fivers was found at Romford Greyhound Stadium and on the next day five more were traced back to a dog track at Southend. The police were closing in and on 28 October a man was arrested and taken to Albany Street. Not long after a flat was searched at 620B Finchley Road near Golders Green tube station.

Brian Donald Hume with his wife Cynthia. At the time of his arrest in October 1949 they had a three month old son. She was a former night-club hostess and went on to marry the crime reporter Duncan Webb.

The man arrested was Brian Donald Hume who had originally met the physically imposing Stanley Setty two years previously at the Hollywood Club near Marble Arch. Hume had been impressed with Setty’s expensive-looking suit with the flamboyant tie and his general overall wealthy appearance: “He had a voice like broken bottles and pockets stuffed with cash,” Hume later recalled.

Setty realised that Hume could be useful for his illegal operations and they became ‘business’ partners dealing with classic ‘spiv’ goods such as black market nylons and forged petrol coupons but also trading in stolen cars which Hume stole for Setty to sell on after a quick re-spray. Hume was also useful as he had qualified for a civilian’s pilot’s licence after the war and had been getting a name for himself within London’s underworld as ’the Flying Smuggler’.

Hume was born illegitimately in 1919 to a schoolmistress who gave her son to a local orphanage to bring up. He was retrieved after a few years and brought up by a woman he knew as ‘Aunt Doodie’ but who actually turned out to be his natural mother. According to Hume she never properly accepted him as she did her other children and he would later comment: “I was born with a chip on my shoulder as big as an elephant.”

In 1939 he joined the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve as a pilot but left in 1940 after getting cerebrospinal meningitis. An RAF medical report at the time, however, described him as having ‘a degree of organically determined psychopathy’.

Hume as RAF Officer c.1943

During the war he bought an RAF officer’s uniform and used his knowledge to masquerade as Flying Officer Dan Hume, DFM. Hume passed off forged cheques at RAF stations around the country (“it was a great thrill to have everyone saluting a a bastard like me”) but he was soon caught and in 1942 he was bound over for two years.

On 1st October 1949, Setty and Hume’s thin veneer of friendship was stripped away during an argument at Hume’s Finchley Road flat. Setty had recently upset Hume by kicking out at his beloved pet terrier when it had brushed up against a freshly re-sprayed car and the confrontation soon became physical. Hume, not a person who particularly found it easy to control his temper, was now in a violent rage and reached over and grabbed a German SS dagger that was hanging on the wall as decoration. He later told a reporter:

I was wielding the dagger just like our savage ancestors wielded their weapons 20,000 years ago . . . We rolled over and over and my sweating hand plunged the weapon frenziedly and repeatedly into his chest and legs . . . I plunged the blade into his ribs. I know; I heard them crack.

Hume stabbed Setty five times after which he lay back and watched his victim’s last breaths. He wrote later: “I watched the life run from him like water down a drain”.

Hume dragged Setty’s hefty thirteen stone into the kitchen and hid the body in the coal cupboard. The next day, while his wife was out, he started to dismember the body with a linoleum knife and hacksaw, eventually wrapping the body parts in carpet felt adding some brick rubble for additional weight. The following morning Hume arranged to have his front room redecorated, and had the carpet professionally cleaned and dyed to get rid of any stray blood stains. What upset him most was having to burn £900 worth of bloodstained five pound notes.

Later that day Hume took the carpet felt parcels to Elstree airport and hired an Auster light aircraft to dump Setty’s remains over the English Channel. It took several attempts, and broke the plane’s window in the process, before Hume was successful in getting the parcels to slide out of the small side-door. As it was now getting dark Hume decided to land at the closer Southend airport and had to hire a car home for which he paid, of course, with one of Setty’s left-over fivers.

The actual Auster light aircraft used by Brian Hume to dispose of Setty’s body.

Brian Donald Hume, 1949.

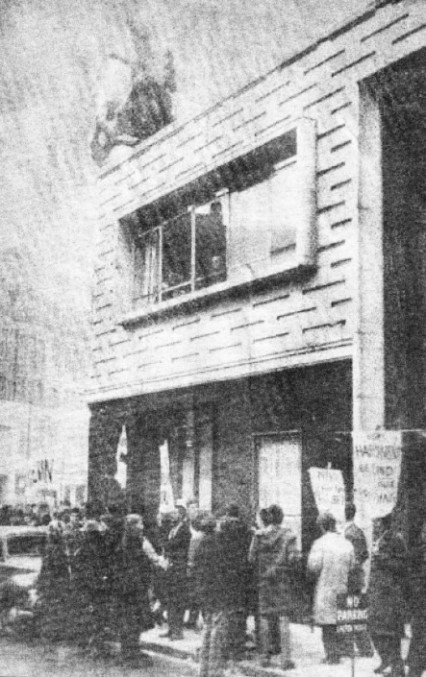

A week after his arrest on 5t November Hume appeared at Bow Street Magistrates’ Court charged that he:

Did, between 4th and 5th October, 1949, murder Stanley Setty, aged 46 years. Against the Peace.

By now there was so much evidence collected by the police including fingerprints, identified torsos, blood-stains found in the flat of the accused, hire cars paid by the victim’s proven money and so on that anyone involved in the case thought that realistically there could only be one verdict.

The trial at the Old Bailey started on the 18 January 1950 and Hume’s defence was based around a story that he had originally contrived for the police. Essentially, it was that he had been paid £150 to dump some heavy parcels over the English Channel by three former associates of Setty called Max, Greenie and The Boy. Hume’s descriptions of the three men seemed so accurate and detailed that the story sounded credible to many in the courtroom.

The defence also called on Cyril Lee – a former army officer who lived within earshot of Setty’s lock-up for three years. He was no friend of Setty’s and admitted that he disliked the sort of men that had been habituating the garage at Cambridge Terrace Mews. He told the court that although that they weren’t ‘the sort of people I would like to see round my doorstep,’ he had heard two people that were called ‘Max’ and ‘The Boy’ and also acknowledged that he had seen a man who looked like Hume’s description of ‘Greenie’.

Queues for Brian Hume’s trial at the Old Bailey, 18th January 1950.

Police officers carry bloodstained carpet and floorboards from the home of Brian Hume into the Old Bailey at his trial, London, 18th January 1950. A week later, Hume was convicted as an accessory to the murder of his business associate Stanley Setty.

The Judge, Mr Justice Sellers, spoke to the jury about the inferences and assumptions they had to make but also told them that if there was any doubt about what had happened then they were compelled to return a verdict of not guilty.

The jury were ready in less than three hours to return their verdict and to most people’s surprise, it was that they had failed to agree on one. Hume was retried, and on the 26th January 1950, and after the judge had instructed the new jury to return a not-guilty verdict for the charge of murder, he was found guilty of being an accessory after the fact. Hume was sentenced to just twelve years in prison but he didn’t hide from the courtroom that he had expected less.

Three years before the case of Setty’s murder caught the imagination of the British public in 1946, George Orwell wrote the essay ‘Decline of the English Murder’. What he thought of the Setty murder case we will never know as on the very same morning that Brian Hume was taken to begin his sentence at Dartmoor Prison, Orwell’s funeral was taking place at Christ Church on Albany Street. The church was situated just round the corner from Stanley Setty’s lock up in Cambridge Terrace Mews and on the very same road where Friswell’s grand Automobile Palace once stood and where Hume was originally taken in for questioning at Albany Street Police Station.

Brian Hume was released from Dartmoor Prison on 1st February 1958. It was almost certainly the only time in Hume’s life that his behaviour was described as ‘good’ but it was for this reason he was released four years early. Because of the law of double jeopardy Hume was secure in the knowledge that he could no longer be retried for murder and he brazenly sold his story to the now defunct Sunday Pictorial. The front page splash began:

I, Donald Hume, do hereby confess to the Sunday Pictorial that on the night of October 4, 1949, I murdered Stanley Setty in my flat in Finchley-road, London. I stabbed him to death while we were fighting.

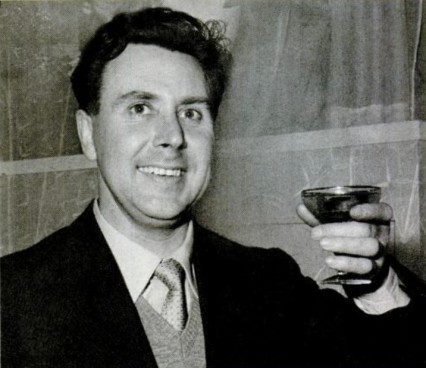

For the benefit of the Sunday Pictorial newspaper Brian Hume was photographed celebrating his release from prison with champagne. It didn’t go down well with the public.

Hume admitted in the article that he had murdered Setty alone and Max, Greenie and The Boy was just figments of his imagination. The astonishing detailed accuracy of the descriptions of the trio that had successfully fooled some of the jury were actually based on the three policemen who had originally interviewed him.

In May 1958 Hume, complete with a false passport and what was left of the money he had received from the Sunday Pictorial, fled to Zurich in Switzerland. To raise more money he started committing bank robberies back in England that were cleverly synchronised with flights at Heathrow enabling him to flee the country before the police had even started their enquiries. Eventually Hume’s luck ran out when he shot and killed a taxi driver after another attempted bank robbery. This time it was in Zurich and Hume was ignominiously captured by a pastry chef before being rescued by the police from a gathering angry crowd.

Hume was at last found guilty for murder and he received a life sentence with hard-labour. In 1976 he was was judged to be mentally unstable by the Swiss authorities and this gave them the excuse to fly Hume back to England where he was incarcerated at Broadmoor Hospital. Hume was eventually released in 1998 but it was just a few months later when his decomposing body was found in a wood in Gloucestershire. The body was identified as Hume’s by it’s fingerprints.

Not unlike the Manson Family killings in 1969 that seemed to bring an end to the peace-loving hippy era and the summer of love, the shocking Stanley Setty murder changed the public perception of the typical Spiv as a loveable rogue forever. There was always something slightly comical about the Spiv and indeed the exaggerated clothes and manners lent themselves to caricature. The spiv-like comedy characters continued to be part of British popular culture for the next couple of decades or so – notably Arthur English’s Prince of the Wide Boys, George Cole’s ‘Flash Harry’ in the St Trinian films, and Private Walker in the early Dad’s Army episodes.

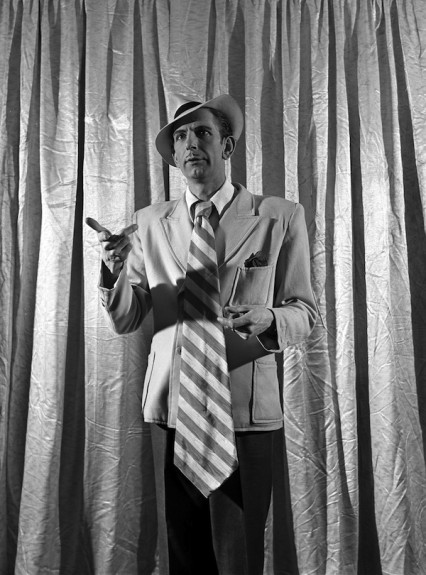

London, 1950. British actor and comedian Arthur English dressed as the spiv known as ‘Prince of the Wide-Boys’.

But it was rationing that gave spivs a major reason to exist and during the General Election of 1950 the Conservative Party actively campaigned on a manifesto of ending rationing as quickly as possible. The issuing of petrol coupons ended in May 1951 while sugar rationing finished two years later and finally in 1954 when the public were allowed to buy meat wherever and whenever they wanted, it brought an end to rationing completely.

By the time Brian Hume was released from prison in 1956, the era of the Spiv had essentially come to an end.