Archive for the ‘Jermyn Street’ Category

Protected: Teddy Boys, Christmas Humphreys and the murder of John Beckley on Clapham Common in 1953

Wednesday, July 20th, 2011The Turkish Baths in Jermyn Street, St James.

Tuesday, April 12th, 2011

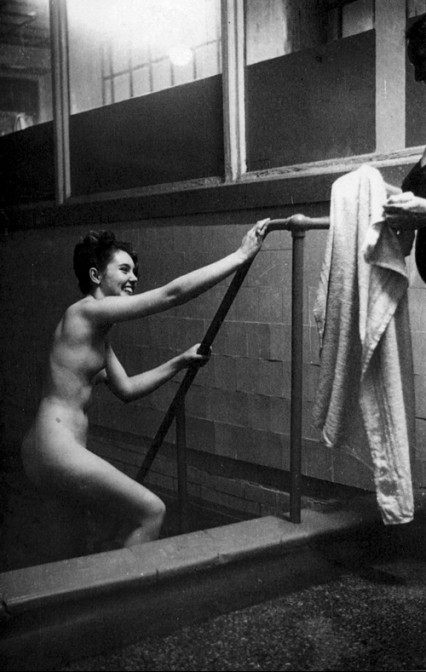

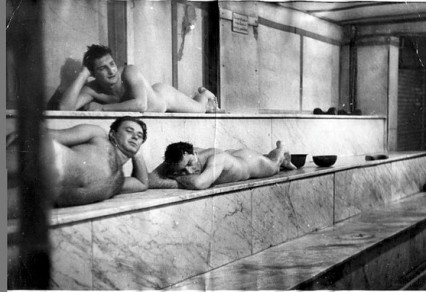

Savoy Turkish Bath in Duke of York Street, 1951 - "A vigorous lathering on a marble slab with a wooden pillow."

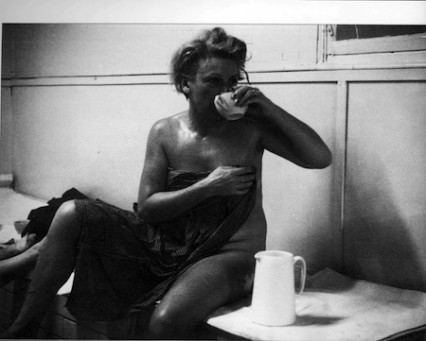

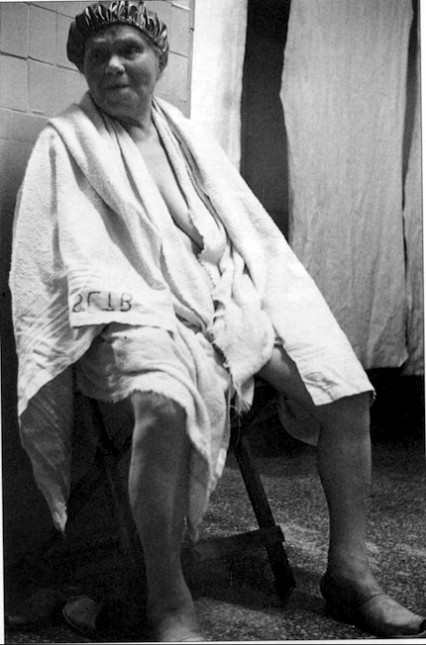

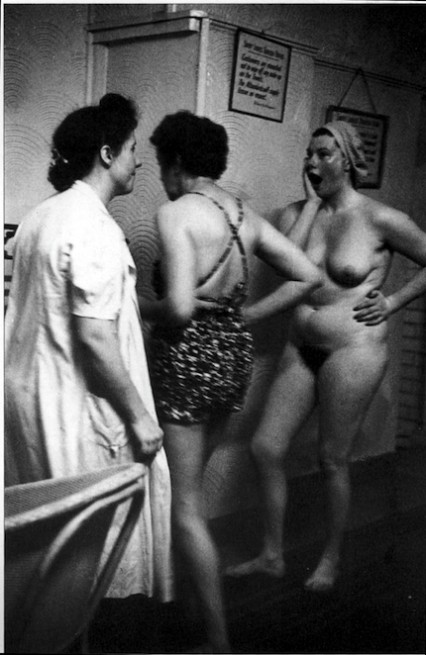

Late in 1951, on a cold foggy afternoon, the type that only London in those days could serve up, a young woman called Grace Robertson, one of the few female professional photographers of the time, spent a day amongst the regular clientele in the tarnished and faded elegance of the Savoy Turkish Baths in London’s St James.

Robertson photographed the customers as they went from one hot room to the next which was then followed by a cleansing pummel in the bath’s marble wash-house. Finally the women plunged into an ice-cold pool had a massage and then took a quick look at the weighing scales before stepping outside into the grey austerity of London in the early fifties.

The women-only Baths were situated at 12 Duke of York Street directly round the corner from the more infamous Savoy Turkish Baths at 92 Jermyn Street.

"Then you plunge into an icy pool...!"

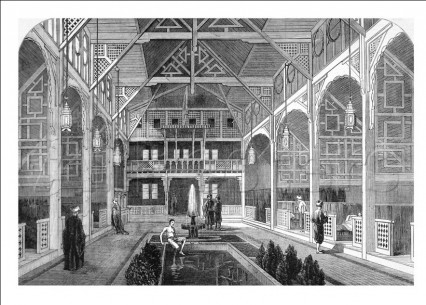

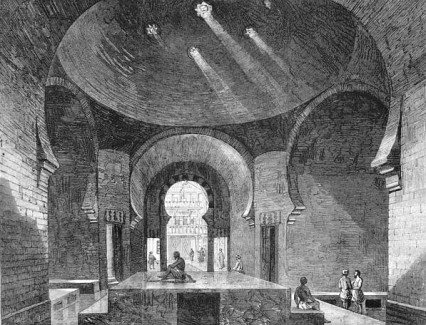

However the Savoy baths weren’t the first Turkish baths to be built in Jermyn Street. In 1862 the London and Provincial Turkish Bath Co. Ltd. built what was said by some to be the finest in Europe at number 76. It was built under the superintendence of the diplomat and Hammam obsessive David Urquhart.

It was Urquhart that had been largely responsible for the the introduction of the Hammam to the UK in the mid-nineteenth century and it was him who actually coined the term ‘Turkish Bath’ that is still used in this country.

He had travelled around Turkey, Greece and Moorish Spain and had been greatly affected by the Hammam’s popularity in these countries and especially how relatively classless they were.

The incredible 'Turkish' Hammam at 76 Jermyn Street.

Urquart reckoned that if Turkish baths could become common-place in the dark and dirty towns and cities around Britain the grubby and filthy life of the workers could in some way be alleviated. He thought the bath houses he proposed to build around the country would contribute to a “war waged against drunkenness, immorality, and filth in every shape.” We won’t know for sure but David Urquhart probably wouldn’t have been entirely happy about some of the behaviour that went on in the Turkish baths in the following century.

By the time the Jermyn Street Hammam had been built there were about 30 Turkish baths in London. All due mainly to the efforts of David Urquhart. These Turkish Baths, as understood by the Victorians, were dry air saunas, different from the Russian steam baths or the Finnish saunas (which has water ladled onto the hot coals), and drier even than the present day Turkish baths or hammams.

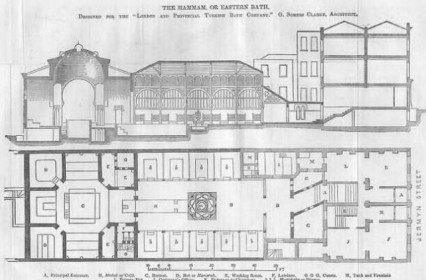

76 Jermyn Street

plan of the Hammam at 76 Jermyn Street

Urquhart gave lectures and wrote pamphlets extolling the return of this ancient method of healthy bathing. Recommending it for people suffering from practically any illness the Victorians thought existed, but including constipation, bronchitis, asthma, fever, cholera, diabetes, syphilis, baldness, alcoholism and even baldness and dementia. Feminine hygiene ailments could also be cured Urquhart maintained, although whatever they were, they apparently weren’t decent enough to discuss in the public forum of a pamphlet.

Not that it particularly mattered as far as the Jermyn Street Hammam was concerned because, like most other Turkish Baths being built in London, when it opened it was men-only. A separate women’s bath, laid out in the original plans, was never built and even Urquhart’s ideal of different classes bathing together didn’t materialise either. No ordinary working man could have afforded 3/6d during the day and as much as 2/- in the evening.

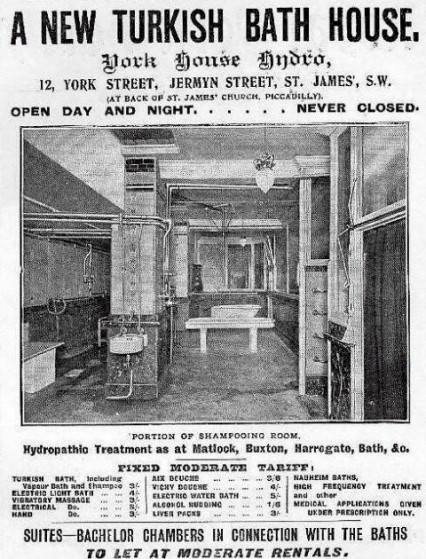

The York House Hydro - opened in 1908 and became the women-only Bath house two years later.

Fifty years later, a less exclusive clientele were catered for in Jermyn Street when the York House Hydro was opened by Ernest Henry Adams in Duke of York Street in 1908. Two years later Adams opened some Turkish baths around the corner at 92 Jermyn Street. The two premises were joined at the back and the original baths in Duke of York Street turned into a Ladies’ Turkish Baths and it was here where Grace Robertson took her beautiful Picture Post photographs in 1951.

Photograph by Grace Robertson for Picture Post in 1951 - "A women's club with a towelling-only uniform."

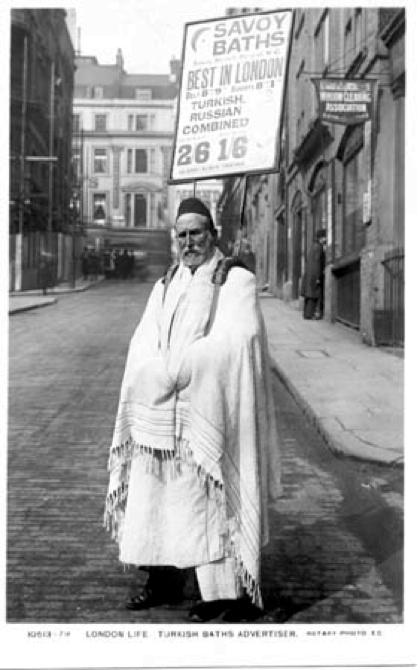

The Savoy Baths, apparently the best in London.

Developments in domestic sanitation had changed the way a lot of people got clean and between the wars there was a huge reduction in the need for municipal bathing facilities and private steam baths in all but the poorer areas of London. The original Jermyn Street Hammam at 76 Jermyn Street although both grand and spectacular closed down at the beginning of the war due to lack of use.

It would never reopen mainly because a few months after the baths closed the site was completely destroyed when a Nazi parachute bomb exploded above Jermyn Street on 17th April 1941. It was the same bomb that ended the life of the popular singer Al Bowly who, when it exploded, was reading a cowboy book in bed in the adjacent Duke’s Court apartments.

The aftermath of a parachute bomb that exploded above Jermyn Street in April 1941.

Jermyn Street today, the Hammam at 76 would have been on the right on the corner of Bury Street.

Meanwhile the exclusively male Savoy Turkish Baths at 92 Jermyn Street remained open, indeed they remained open all night long and not surprisingly soon they became popular with gay men not least because of the ‘bachelor chambers connected to the bath’ that could be ‘let at moderate rentals’.

After the war, in an attempt to survive as ongoing concerns, the remaining Turkish baths in London, and especially the Savoy, started to subtly encourage their gay clientele while at the same time subduing their internal policing. Hunter Davies in the New London Spy wrote:

“Staff mostly turn a blind eye to much of the midnight prowling…if the activity is not too blatant.”

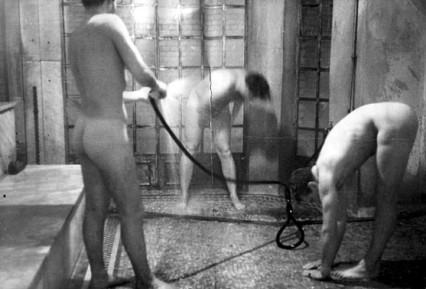

Photographs by Maurice Ambler in 1951, also for Picture Post

"The Turkish Bath embraces the classical and Oriental ideal. Even the Roman names are retained. The present-day bather strips off and rests in the Frigidarium, starts to sweat in the Tepidarium, and finishes in the Caldarium." - Picture Post 1951

However the baths had always had a bit of a gay reputation and it was to the Savoy Turkish baths that Christopher Isherwood and WH Auden took the 24 year old Benjamin Britten in 1937. This would have been around the time of their collaboration for the famous GPO film Night Mail which was produced by Basil Wright.

“Well,” Basil asked Isherwood afterwards, “have we convinced Ben he’s queer, or haven’t we?” Britten wrote in his diary of his experience at the baths: “Very pleasant sensation. Completely sensuous, but very healthy. It is extraordinary to find one’s resistance to anything gradually weakening.”

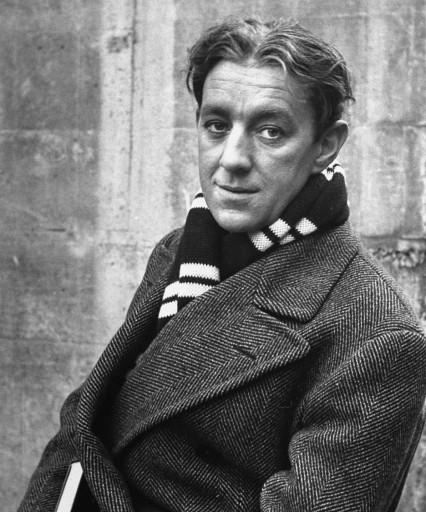

Benjamin Britten and WH Auden in the late thirties.

Derek Jarman once wrote of the infamous Savoy Baths in Jermyn Street:

“as a young MP, Harold Macmillan – who was expelled from Eton for an ‘indiscretion’ – used to spend nights at the Jermyn Street baths; anyone who went to them would have been propositioned during the course of an evening. I went there myself on two or three occasions. They were a well-known hangout: dormitory and steam rooms full of guardsmen cruising.”

One of the attractions of the Savoy baths were the amount of famous people to be seen there. The Turkish baths were was one of the few places a closeted gay actor, of which it would be fair to say there would have been quite a few, could feel reasonable safe from the police. Alec Guinness was a regular there, although he wrote in his diary, “it all revolted me”. Although it apparently so revolted him he kept on going back.

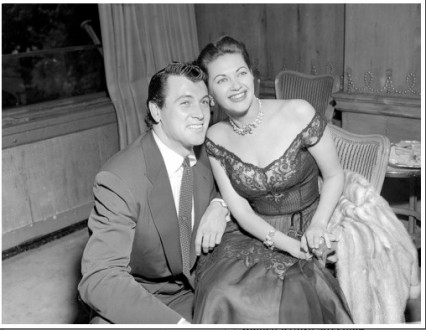

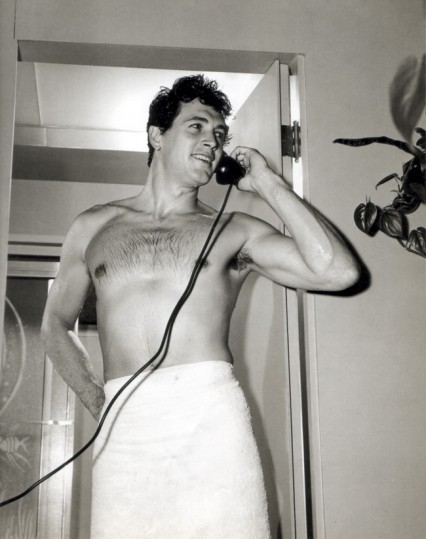

The closeted gay actor Rock Hudson would also often visit the Jermyn Street baths perhaps after trying the various after-shaves available in the Dunhill shop across the road (which is still there). However the cinema-going public in the UK remained blissfully unaware of the young actor’s nocturnal steamy proclivities and were fed plenty of publicity shots of Hudson with the latest pretty starlet.

Rock Hudson and Yvonne de Carlo in London, August 1952. They were publicising the film Scarlet Angel.

Hudson was lucky though, because in 1985 the Daily Mirror ran a story that the 27 year-old had actually been arrested and thrown out of the Savoy baths in 1952 for importuning. Presumably they had been sitting on the story for thirty-three years before daring to publish it.

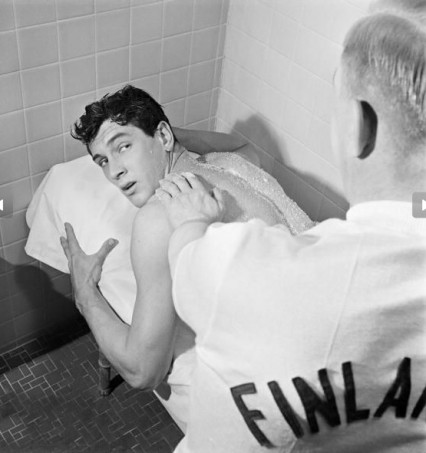

Rock Hudson in 1952

The incident happened relatively early in Hudson’s career although it was four years after his first film ‘Fighter Squadron’ (he had only one line but it took him 38 takes to get it right). It would be another two years in 1954, however, before he starred in his first big hit film called ‘Magnificent Obsession’ which propelled him into a career as an actor who epitomised ‘wholesome manliness’.

Presumably it was relatively easy for Universal to keep their young acting protégé they were carefully grooming out of the papers. It almost certainly wasn’t the first time this happened and certainly not the last. His hastily arranged marriage to Phyllis Gates the secretary of his agent in 1955 was a direct result of Confidential magazine threatening to expose his hidden gay lifestyle.

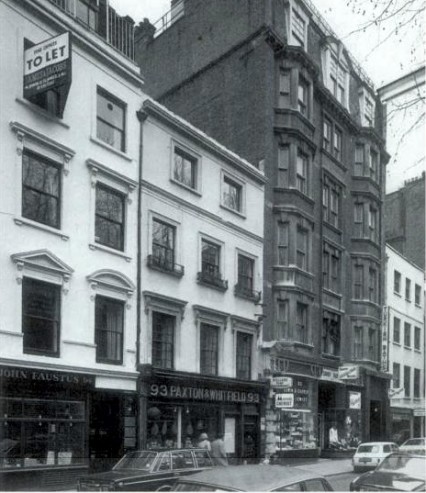

The Savoy Turkish baths in Jermyn Street, 1955

Strangely, over the years, considering the general night-time activities that went on, the Savoy didn’t get into too much trouble with the authorities. Whether it was the relatively high-prices that kept blackmailers at bay or the the police just chose to show a blind eye we don’t know. Ironically, however, it wasn’t until homosexuality was legalised that raids on the baths became more common.

The New London Spy, a rather self-conciously trendy guide book for London published in the late sixties, wrote about the remaining Turkish baths in London (essentially they meant the Savoy in Jermyn Street which of course was just down the road from Piccadilly Circus – a pick-up location known in gay parlance at the time as the ‘Wheel of Fortune”):

“If you adopt the Boy Scouts’ motto Be Prepared you should be able to spend a night at the Turkish Baths…the steam has a peculiar effect on some chaps.” A later edition published in the seventies was already warning that “Sauna and Turkish baths are regularly raided and/or change management, check daily.”

Whether it was because the Savoy baths were unprepared for changing fashions or the police raids became too frequent, the inevitable happened and the last of the Jermyn Street baths closed down forever in 1975. The women’s baths in Duke of York Street, perhaps always a bit of a mismatch in the male preserve of Jermyn Street and its environs, had closed much earlier in 1958; just seven years after Grace Robertson took her photographs for the Picture Post.

92 Jermyn Street today

Duke of York Baths "Trepidation on the threshold of the first steam room."

"After all that, I haven't lost an ounce!"

Thank you to Malcolm Shifrin at www.victorianturkishbath.org