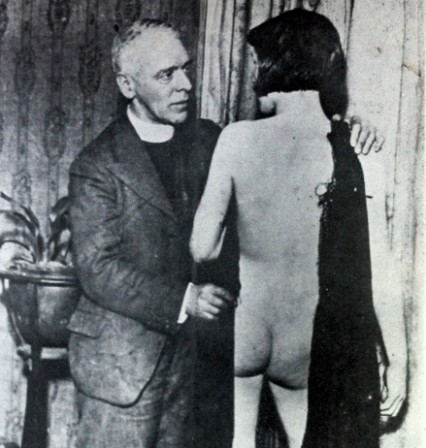

The Rector of Stiffkey, Harold Davidson with Estelle Douglas 1932

‘It is very hard to be good, once you have been bad.’ - Barbara Harris

The Reverend Harold Francis Davidson, the Rector of the small Norfolk parish of Stiffkey for twenty-five years, was utterly besotted and bewitched by pretty young girls – of that there was no doubt. How he behaved in the company of said pretty young girls was more up for debate; and in 1932 it seemed the whole country, including the highest echelons of the Church of England, was debating exactly that.

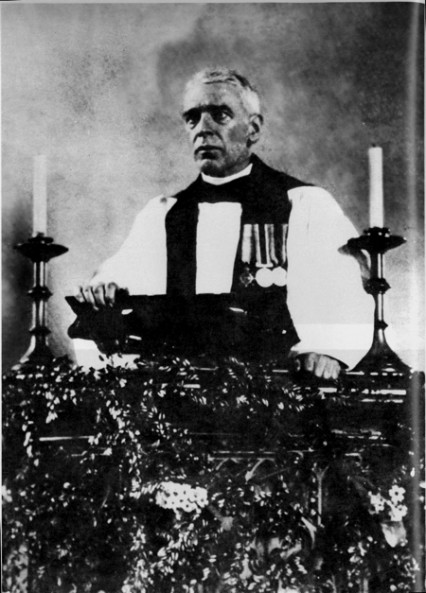

The Rector preaching at Stiffkey

Every Sunday, from 1906 to 1932, with a break for the First World War when he joined the Royal Navy, the Reverend Davidson was always at his pulpit at the Stiffkey church. He spent the rest of the week, however, in Soho in London, catching the first train every Monday morning and the last one back to Norfolk on Saturday night.

The Stiffkey locals joked that especially in the summer it was best not to die on a Monday morning as the body, by the time the reverend made it back for the funeral, would be rather malodorous. He was well-liked all the same by most of his local parish.

During the week Davidson, often without his dog-collar, would walk around the streets of the West End essentially stalking and pursuing girls wherever he went.. Whether it was attactive young actresses, shop girls or waitresses none of them were particularly safe from the the glint in the Reverend’s eye.

Until the day he died the Rector always argued that he was doing nothing else but God’s work as he wondered around Soho. His aim in life, he claimed, was helping young women, particularly shop-assistants and waitresses, many of whom had left home for the first time and were on very low wages, from falling into a life of prostitution. He once said:

I cannot help feeling, that is, say, half the London clergy would, individually, spend a quarter of the time I spent looking after country girls stranded in London…instead of wasting their time…at gossiping Mothers’ Meeting, Parish Tea fights, and Society functions, there might not be so many thousands of the poor, misguided girls openly, shamelessly plying their terrible trade.

At his own estimate Davidson had made the acquaintance of, in one way or another, two to three thousand girls between 1919 (when he returned home from the First World War to an adulterous and pregnant wife) and 1932:

I was picking up in this way roughly, as my diaries show, an average of about 150 to 200 girls a year, and taking them to restaurants for a meal and a talk, of these I was able definitely to help into good jobs of work a very large number.

When Davidson talked about ‘restaurants’ he almost certainly would have been talking about relatively cheap cafes such as the J. Lyon’s Tea Shops of which there were many around London, and indeed around the country, in the twenties and thirties. The first of the Lyons teashops opened at 213 Piccadilly in 1894 (it’s still a cafe, now called Ponti’s and you can still see the original stucco ceiling of the original teashop).

Soon there were more than 250 white and gold fronted teashops occupying prominent positions in many of London’s high streets. Food and drink prices were the same in each teashop irrespective of locality and the tea was the best available although the Lyons blend was never sold or made available to the public.

The J. Lyons flagships shops were the Corner Houses situated on or near the corners of Coventry Street, the Strand and Tottenham Court Road. They were started in 1909 and remained until 1977. They were gigantic places with food being served on four or five floors. In its heyday the Coventry Street Corner House served about 5000 covers and employed about 400 staff. There were hairdressing salons, telephone booths and even at one point a food delivery service. For a time the Coventry Street Corner House were open 24 hours a day.

Lyons Corner House, Coventry Street.

The hot food counter in Lyon’s Corner House restaurant in Coventry Street. The bar is made of functional steel, with built-in hot water jets and a row of tea urns, which is in marked contrast to the classical styling of the rest of the restaurant.

Davidson at a Foyles Literary Luncheon at the Grosvenor House Hotel, London. “I could get you in films, you know”.

An associate of the Reverend Davidson called J. Rowland Sales once referred to an incident that occurred in the large Coventry Street Corner House while they were drinking tea together. Davidson was telling a very sad story about a homeless couple he had recently found sleeping under a hedge in Norfolk and became visibly upset. All of a sudden, however, his demeanour changed instantly and it was almost like he was a completely different person, recounted Sales. The reason was because a young ‘nippy waitress’ had walked by. Suddenly Davidson called out ‘Excuse me, Miss. You must be the sister of Jessie Matthews‘, before leaping up and rushing out of the teashop promising the startled waitress that he would get her a part in a new play that was opening in London.”

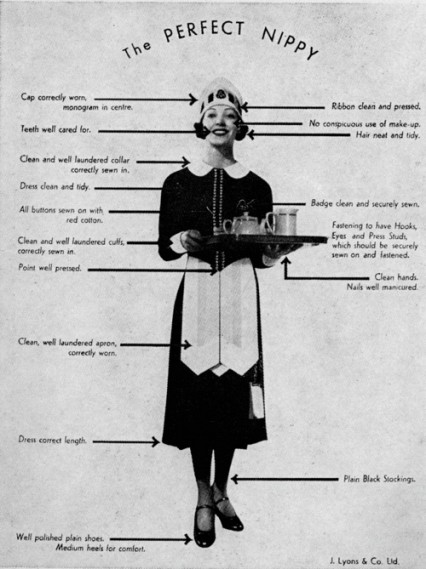

Lyons’ Nippy waitresses

In 1926 there was a staff competition to name to choose a nickname for the Lyon’s teashops’ waitresses – the former name of ‘Gladys’ was now seen as old fashioned. The waitresses wore starched caps with a big, red ‘L’ embroidered in the centre, a black Alpaca dress with a double row of pearl buttons sewn with red cotton and white detachable cuffs and collar, a white square apron worn at dropped-waist level. The name ‘Nippy’ was eventually chosen for the connotation that the waitresses nipped speedily around – often trying to avoid the advances of middle-aged men like Harold Davidson no doubt.

The Perfect Nippy

It was once reported by Picture Post that 800-900 Nippies got married to customers ‘met on duty’ every year and they wrote that ‘being a Nippy is good training for a housewife’. If ‘Nippy’ sounds a trifle strange as a name for a waitress, its worth noting that other rejected suggestions included ‘Sybil-at-your-service’, ‘Miss Nimble’, Miss Natty’, ‘Busy Betty’ and even ‘Dextrous Doris’.

The strange and rather bizarre stories of Reverend Davidson behaviour in Soho eventually came to be noticed by his employer – the Church of England, notably the Bishop of Norwich. In 1931 the Bishop decided to investigate Davidson, and soon the self-styled Prostitutes’ Padre was charged with offences against public morality under the 1892 Clergy Discipline Act.

A consistory court, which is a type of ecclesiastical court used by the Church of England to this day for the trial of clergy (below the rank of bishop) accused of immoral acts, opened at Church House in Westminster on 29 March 1932. A Consistory court has no jury and is presided over, in place of a judge, by what is called a Chancellor of the Diocese.

The original Church House was founded in 1887 and built to commemorate the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria. It was knocked down and replaced in 1937 the year of Davidson’s death.

Inside Church House

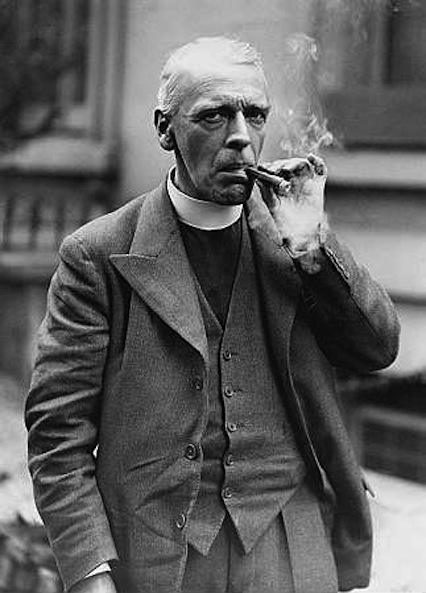

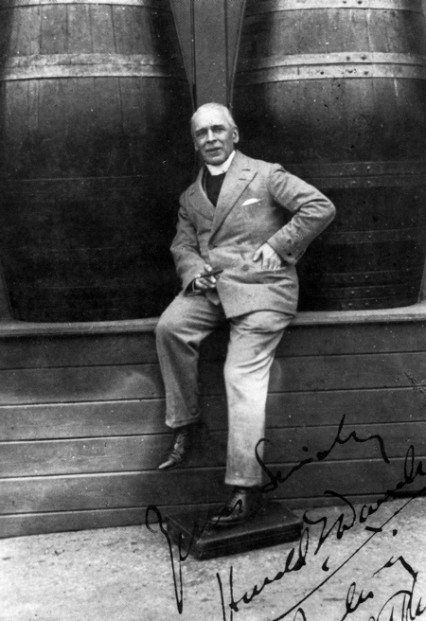

The court case was a sensation and front page news. Davidson wasn’t slow in courting the press and on the first day of the trial arrived in flamboyant style while smoking a characteristic large cigar. He even signed autographs.

Harold and his cigar

Davidson’s Family outside Church House in Westminster

Amongst, what seemed like hundreds of Nippies and domestic servants brought up to give evidence, the prosecution’s star witness was a young woman called Barbara Harris whom Davidson had met in 1930. He had first seen her at Marble Arch – a popular haunt of prostitutes at the time – and he used his old tried and tested trick of comparing Barbara to a famous actress, this time Greta Garbo.

Barbara was just sixteen and already a prostitute suffering from gonorrhea. She had never known her father and been abandoned by her mother who suffered from mental illness. She welcomed the kind gentleman’s offer of help and was soon pouring out her life-story to Davidson, no doubt in a Lyons cafe in the near vicinity. Davidson helped her find lodgings and they became close over the next 18 months.

Rosie Ellis, one of the main witnesses at Davidson’s trial.

Star proscecution witness Barbara Harris arriving at the church court. 1932

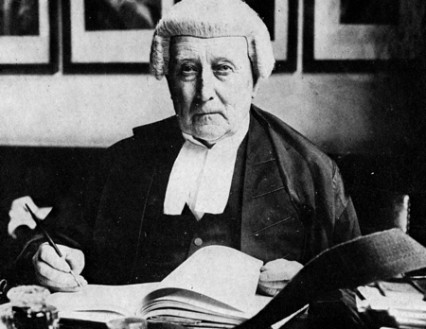

The Worshipful F. Keppel North, the Chancellor of the Diocese of Norwich ie the Judge.

The rector gave Barbara money and even found her a job in domestic service at Villiers Street in Charing Cross but she quickly tired of both the job and the reverend’s repeated attentions. At one point she gave him a black-eye and threw coins at him but he continually came back for more.

One morning at 9 am Davidson had appeared at the room where she was sleeping. During the court case the prosecution asked Barbara about this:

Prosecution: What did he do?

Barbara: He tried to have intercourse with me.

Prosecution: Did you let him?

Barbara: No

Prosecution: When you refused, did he say anything?

Barbara: He said he was sorry afterwards.

Chancellor: When he tried to have intercourse with you, did he do anything to his clothes?

Barbara: Yes, he said he got them into a mess.

Chancellor: Did he undo his clothes?

Prosecution: Did he do anything? You said something about his clothes being in a mess?

Barbara: He relieved himself.

Prosecution: Did that happen more than once?

Barbara: More than once. It happened two or three times.

Prosecution: You say you kissed him?

Barbara: Yes.

Prosecution: How often was he kissing you?

Barbara: He was always kissing me.

Prosecution: Did he ever ask you to do things?

Barbara: Yes, he once asked me to give myself to him body and soul…

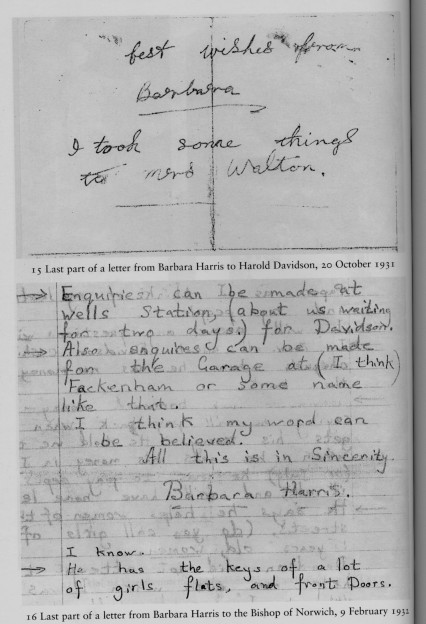

“I know he has the keys of a lot of girls flats, and front doors” – a letter from Barbara Harris to the Bishop of Norwich.

If this wasn’t enough, near the end of the trial additional evidence was suddenly produced which ultimately finished Davidson’s clerical career.

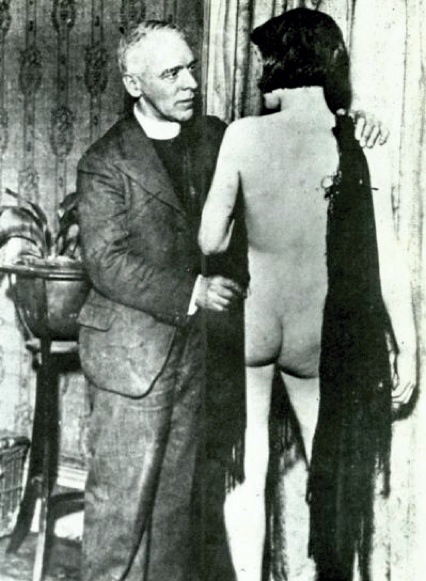

To Davidson’s utter shock and horrified disbelief, the prosecution produced a photograph of the reverend standing next to a naked 15 year old actress. The girl was called Estelle Douglas and was the daughter of a friend of his – an actress he had helped to get on stage some twenty years before. In turn she had asked Davidson to try and get her daughter into films.

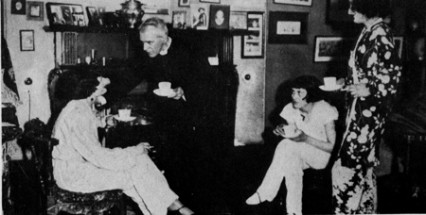

The rectory rather naively holding a pyjama party with young actresses to be, including Estelle Douglas, 1932.

A photoshoot had been organised at the Stiffkey rectory with the idea of taking publicity shots of Estelle in her bathing suit. At one point the photographer told Estelle that the strap of the bathing suit and her chemise were both showing and, apparently out of earshot of the Reverend, asked her to remove them, leaving her with a black tasselled shawl to protect her modesty. A series of photographs were then taken.

Harold Davidson rushing to protect the young actress’s modesty. 1932

According to Davidson the photographer offered fifty pounds to take a photograph of him and Estelle with the intention of selling it to the newspapers. Davidson was broke and needed the money and rather stupidly agreed to the request. Whether the photograph was set-up or not (there is evidence to suggest that it was) it was now all over for the ‘Prostitute’s Padre’ and the court found him guilty of five counts of immoral conduct. He was charged £8,205 costs and his career in the Church was finished.

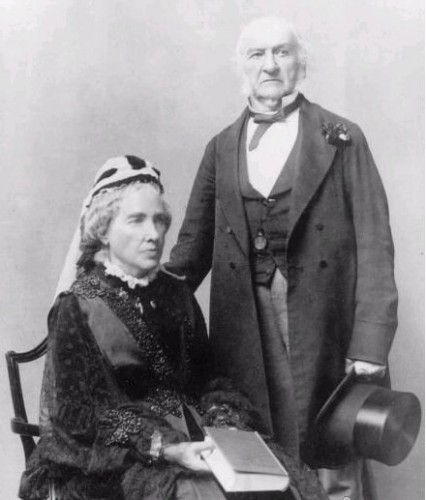

Mr and Mrs Gladstone. Their marriage was happier than it looked. Despite the prostitutes.

Of course the Reverend Davidson wasn’t the first member of the establishment who seemingly spent most of his spare time giving a helping hand up to fallen women in central London. Extraordinarily finding time while being Prime Minister four times, the Chancellor of the Exchequer four times, passing the third Reform Act and trying to establish home-rule in Ireland, William Ewart Gladstone was notorious for wandering around the darker environs of the West End.

With almost reckless abandon he searched for young women to ‘rescue’ often asking them back to his house. A shocked Private Secretary once asked him ‘What would your wife say?’. ‘Why’ Gladstone answered, ‘it is to my wife that I’m bringing her’. His wife Catherine would indeed feed the women and give them a place to sleep before finding, not always particularly gratefully, a temporary shelter to stay. Catherine Gladstone once astutely wrote that it was ‘a common thing for [servants] to be engaged without wages or clothes and only for ‘food every other day’. Who can wonder at girls so situated yielding to temptation and sin?’

Although Gladstone was completely open about his ‘rescuing’ of the young street women, even he wrote in his diary that he had occasionally committed ‘adultery of the heart’ and ‘delectation morosa’ meaning ‘enjoying thinking of evil without the intention of action’. Indeed a fellow parliamentarian called Henry Labouchere, MP for Northampton, wryly noted that:

‘Gladstone manages to combine his missionary meddling with a keen appreciation of a pretty face. He has never been known to rescue any of our East End whores, nor for that matter it is easy to contemplate his rescuing any ugly woman and I am quite sure his convention of the Magdalen is of incomparable example of pulchritude with a a superb figure and carriage.’

Gladstone spent a minimum of £2000 a year helping prostitutes and providing shelters. He lived until the ripe old age of eighty-nine with an extraordinarily full political life. Less than forty years later, at the age of just fifty-seven the former Rector of Stiffkey and the self-styled ‘prostitutes’ padre’ found himself on the scrap-heap. He picked himself up and, using his experience on the stage as a young man, he turned himself into a showman in order to attract as much publicity and money as possible. He wanted to appeal his court case and believed he should have been tried by a jury.

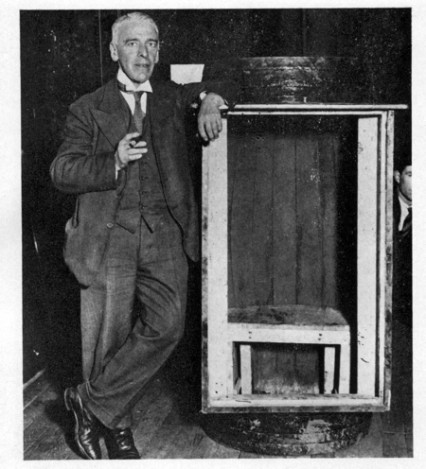

His most imfamous stunt involved him fasting inside a barrel at Blackpool. The container was fitted with an electric light and a small chimney from which his cigar smoke could escape. Through a grille he’d protest his innocence to anyone who would listen and even invited Ghandi to meet him there for tea. To no avail I might add.

The Rector with his barrel.

Davidson in Blackpool in 1933 outside the barrels.

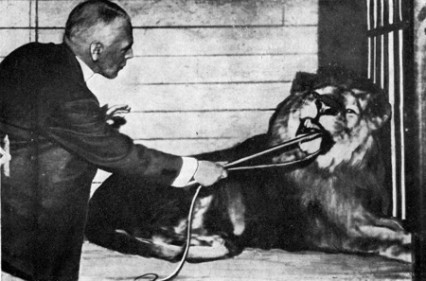

Despite his stunts becoming more and more outrageous, for instance at one point he was being roasted in an oven while being prodded in the buttocks with a pitchfork by a mechanical devil, the erstwhile clergyman’s fame was beginning to wane. In the summer of 1937 Davidson tried one more stunt and at Thompson’s Amusement Park in Skegness he was billed as ‘A modern Daniel in a lion’s den.” Davidson stood in a cage with a lion called Freddie and a lioness called Toto. Again he spoke about the injustice he had been dealt merged with a torrent of abuse against his former church leaders.

Rector with Freddie the Lion in 1937, Skegness.

Unfortunately on the 28th July Davidson accidentally stood on Toto’s tail. Presumably because of the lioness’s sudden movement Freddie attacked the former rector. The lion mauled him around the neck and shook him around like a rag-doll.

Despite the bravery of a 16 year old lion tamer called Renee Somer who fought the lion back using a whip and an iron bar, Davidson was admitted to Skegness Cottage Hospital. It is said that the publicity-hungry Davidson, with blood pouring from his neck, still had the presence of mind to say:

“Telephone the London newspapers – we still have time to make the first editions!”

The badly injured Davidson died in hospital two days later and a verdict of misadventure was returned at the inquest. He was buried in Stiffkey churchyard and with the help of the police to control the crowds, over two thousand mourners attended the funeral.

Looking back eighty years ago, Harold Davidson was almost certainly badly treated by his bishop and the Church of England. He could always be accused of extreme naivety and extraordinary eccentricity but was probably only guilty of an avuncular caress or two (alright lots of avuncular caresses!). However evidence of true immorality was almost non-existent and almost certainly he helped hundreds of young women away from a life of prostitution.

Harold Davidson’s grave at Stiffkey in 2010.

Binnie Hale talks about her role in ‘Nippy’ the 1930 musical