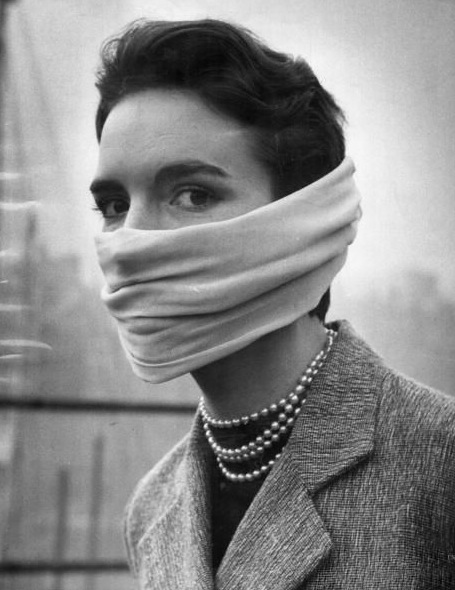

The model Julie Harrison

On Saturday 6 December 1952 the performance of La Traviata at Sadler’s Wells was abandoned at the interval. The incessant coughing of the audience had become intolerable due to the dense ‘pea-souper’ smog which had been slowly creeping into the auditorium making the stage almost invisible to the people who had sat further back.

Further west across London the greyhound racing at White City was halted when the dogs couldn’t see the hare, and reportedly a Mallard duck flying blindly across London smashed into Victoria station and crash-landed onto platform 6.

Before the dense fog had enveloped London the weather for the previous few weeks had been colder than normal. Houses throughout the capital, in those pre-central heating days, were burning large amounts of coal in a million fires and stoves – all of which were emitting a particulate-ridden sulphurous acidic smoke.

Although it had been cold, the weather had been relatively fresh and clear but by Thursday 4 December the conditions began to worsen. The breezes stopped and the skies became greyer and the atmosphere noticably dank.

By the next day the whole city had started to appear like a scene from Dickens’ Bleak House:

Fog everywhere. Fog up the river, where it flows among green aits and meadows; fog down the river, where it rolls defiled among the tiers of shipping, and the waterside pollutions of a great (and dirty) city…Chance people on the bridges peeping over the parapets into a nether sky of fog, with fog all round them, as if they were up in a balloon, and hanging in the misty clouds.

The fog on that Friday morning was thicker than anyone could remember even by people who had long considered the London smog just another aspect of living in the capital. Incidentally the portmanteau smog was coined only forty five years earlier, by HA Des Voeux, who first used it in 1905 to describe the conditions of fuliginous (sooty) fog that occurred all too often in the capital city.

The unpleasant impermeable fogs had been a feature of London for centuries and it wasn’t just Dickens who wrote about, as he would call it, the London Particular. Descriptions of the London fogs can be found in the Sherlock Holmes’s stories and in Louis Stephenson’s Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. The mythical quality of the London fog was reflected in practically any Hollywood film set in London even many years after the era of the London ‘pea-soupers’ had passed. Indeed the great smog of 1952 was the beginning of the end of the eye-stinging London Particulars.

By nightfall on Friday 5 December the smothering fog thickened and visibility in most of London dropped to a few metres. During the next day the sun was too weak and low in the sky to make much of an impression on the fog and that night, and on the Sunday and Monday nights, it again thickened. In most of London it was almost impossible for pedestrians, totally disorientated through lack of familiar landmarks, to find their way home.

Because of the dirt and the vile, clogging, unpleasant taste of the smog, many people held ‘masks’ of gauze, scarves or handkerchiefs to their faces. On the Isle of Dogs, almost surrounded by the Thames, visibility was occasionally officially reported to be nil – the fog was so dense that people could not see their own feet.

Hospitals were soon filled with patients suffering from acute respiratory diseases and, almost un-noticed, deaths in the city began to mount. No one noticed at first until undertakers started to run out of coffins and florists were running out of flowers. The very ill weren’t helped by ambulances searching in vain for victims and clanging their bells frantically while unable to extricate themselves from the snail-paced traffic jams.

This London smog, compared with a normal fog or even other urban smogs, was especially lethal after the war because it contained high quantities of sulphur oxides from the cheap sulphurous coal (the better quality hard coal was being exported) that reacted with the moisture in the air to produce a diluted, but lung-corrosive, sulphuric acid mist. The killer brew, to some people, triggered massive inflammation of the lungs – in other words thousands of people were dying almost through suffocation.

The British Committee on Air Pollution finally estimated that during the five days that the smog smothered London there were 4,000 more deaths than would have occurred under normal circumstances. During the next two months it was thought another 8,000 deaths were caused by a direct result of the killer smog. Even during the next summer the death rate was 2% higher than normal.

Legislation followed the Great Smog of 1952 in the form of the City of London (Various Powers) Act of 1954 and the Clean Air Acts of 1956 and 1968. These Acts banned emissions of black smoke and decreed that residents of urban areas and operators of factories must convert to smokeless fuels.

Nothing on the scale of the 1952 Great Peasouper has ever occurred again and it remains the nation’s worst single air pollution disaster. There has been an astonishing hundred-fold reduction in atmospheric particulate levels in London over the last fifty years and the air, in most respects, is cleaner in the capital city than at any other time since the middle ages.