“I do not approve, but I must not pretend to misunderstand” – Eamon de Valera

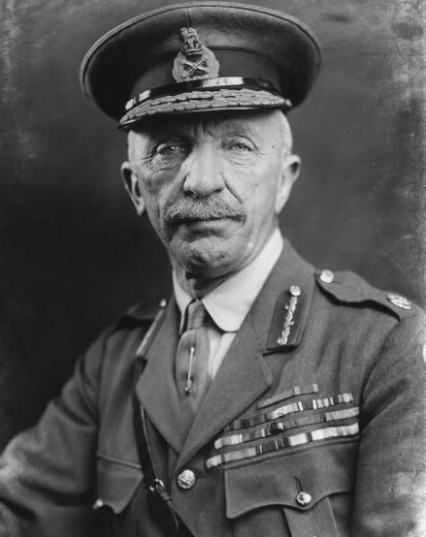

At around midday of 22 June 1922, Field-Marshall Sir Henry Wilson unveiled a war memorial at Liverpool Street Station. He made a speech, quoted some relevant Kipling poetry and returned soon after by taxi to his home at 36 Eaton Place in Knightsbridge. Two 24 year old men, Reginald Dunne and Joseph O’Sullivan, were surreptitiously waiting for his arrival. They watched while Wilson paid for his taxi before running up to him killing him in cold blood and on the footsteps leading up to his front door. In Dunne’s words:

“I fired three shots rapidly, the last one from the hip, as I took a step forward. Wilson was now uttering short cries and in a doubled up position staggered towards the edge of the pavement. At this point Joe fired once again and the last I saw of him he (Wilson) had collapsed”.

The Field Marshall had half withdrawn his sword in a futile effort to protect himself but after being shot seven times he fell face first on to the pavement with blood running profusely from his body and mouth. Dunne and O’Sullivan started to run but the latter man had been seriously wounded at Ypres during WW1 (both men had fought for the British) and his wooden leg severely hindered their escape. The two men attempted to shoot their way out of trouble and shot and injured two policemen and a civilian in the process. They were soon surrounded by an angry and hostile crowd but were quickly arrested by the police who had to protect the two men from the mob who wanted instant revenge for Wilson’s death.

Field-Marshall Sir Henry Wilson, the famous and gallant soldier, was murdered yesterday upon the threshold of his London home. The murderers were Irishmen. Their deed must rank among the foulest in the foul category of Irish political crimes.

Six months earlier at 2.20 am 6th December 1921 the Anglo-Irish Treaty had been signed between an Irish delegation, led by Michael Collins, and the British Government at 22 Hans Place. There is nothing on the outside of the building commemorating this historical event and today, in what is probably one of the most expensive property areas of London, it seems to be unused and empty with security boards up in the windows.

The treaty envisaged an independent Ireland that would be known as the Irish Free State but the agreement was hugely controversial, especially back in Ireland. De Valera, the President of the Irish Republic, had a difficult relationship with Collins at the best of times and was angry that the treaty was signed without his authorisation – although it was at his insistence that Collins went, with de Valera considering it wrong to be involved in the negotiations if Britain’s King George V wasn’t either. The British insistence that they would continue to control a number of ports, known as the Treaty Ports, for the Royal Navy was also controversial. It also displeased many that Northern Ireland (which had been created in the Government of Ireland Act 1920) was also able to leave the Irish Free State within one month, which of course it duly did.

In April 1922 a group of 200 anti-treaty IRA men occupied the Four Courts of Dublin in defiance of their Government. Collins, wanting to avoid Civil War at all costs, decided to leave them alone. It was assumed by the British that Dunne and O’Sullivan were anti-treaty IRA men and after the shock of the Field Marshall’s murder Winston Churchill wrote to Collins threatening that unless he moved against the Four Courts anti-treaty garrison he (Churchill) would use British troops to do so for him. After a final attempt to persuade the men to leave the Courts, Collins borrowed two 18 pounder Artillery guns from the British and bombarded the Four Courts until anti-treaty garrison surrendered. It was a surrender that almost immediately led to the Irish Civil War. Fighting soon broke out over Dublin and subsequently the rest of the country.

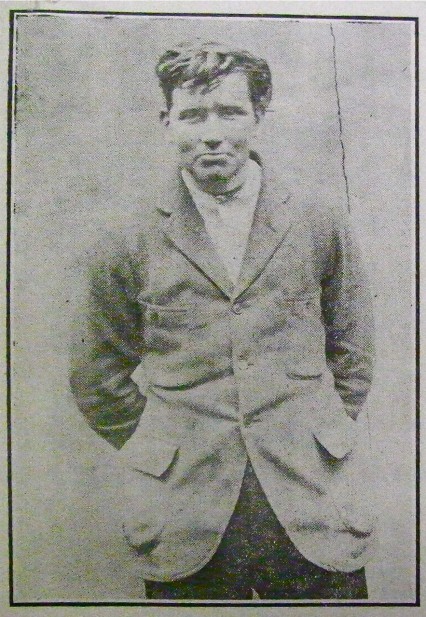

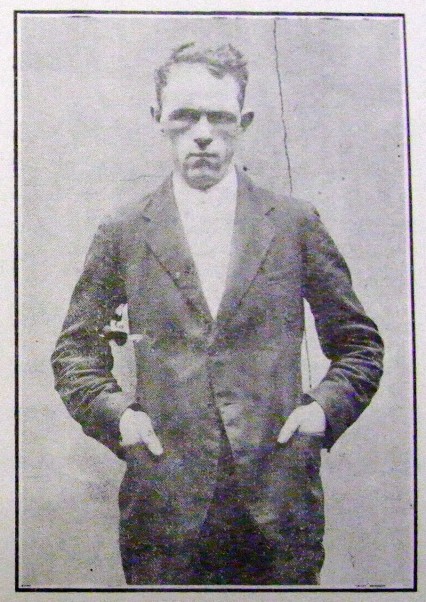

Meanwhile back in London at the Old Bailey, and before Mr Justice Shearman, Dunne and O’Sullivan were both tried together for the murder of Sir Henry Wilson on 2 July 1922. Dunne stood with his arms folded while the charge was being read while O’Sullivan stood stiffly at attention. When Dunne was asked, “Are you guilty or not guilty?” he replied “I admit shooting Sir Henry Wilson.” “Are you guilty or not guilty of the murder?” the Clerk of Arraigns repeated. “That is the only statement I can make,” was the response. O’Sullivan made a similar reply and after some discussion the plea was treated as one of “Not guilty.”

Towards the end of the trial, which lasted just three hours, the defence Counsel handed the judge a double sheet of blue official paper given to him by Dunne. After perusing the contents Mr Justice Shearman said – “I cannot allow this to be read. It is not a defence to the jury at all. It is a political manifesto…I say clearly, openly, and manifestly it is a justification of the right to kill.”

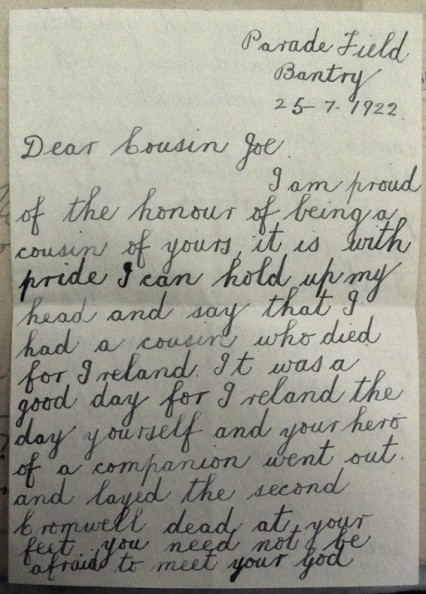

Dunne and O’Sullivan were sentenced to death and were sent to Wandsworth gaol where they were both hanged by the executioner John Ellis on the 10th August 1922.

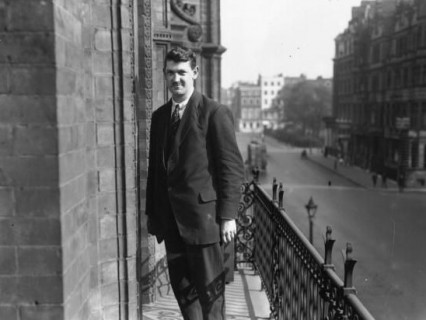

Less than two weeks later Michael Collins was ambushed and shot dead in his home county of Cork by anti-treaty IRA members.

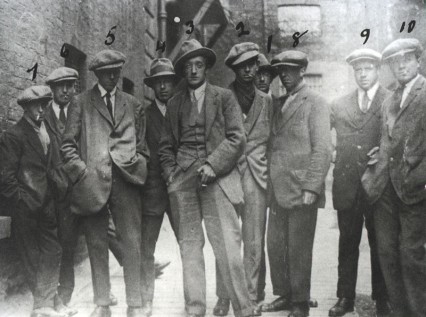

Commander in Chief Michael Collins in July 1922, two or three weeks before he was assassinated in Cork.

It was never really established whether Dunne and O’Sullivan acted on their own (the assassination seemed pretty badly organised for an official assassination so this was likely) or with the approval and help of Michael Collins. Collins had been a friend of Dunne’s at the same time as Sir Henry Wilson had been establishing the Cairo Gang (a group of experienced British Intelligence agents who met frequently at Dublin’s Cairo Cafe) twelve of whom were murdered by the IRA acting under Collins’ command in 1920. The Cairo Gang killings provoked the British Auxiliaries in Dublin to shoot trapped innocent civilians at Croke Park in not the bloodiest but perhaps the nastiest of the various historical Bloody Sundays.